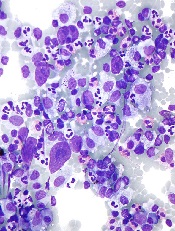

showing Hodgkin lymphoma

NEW YORK—Using a 3-pronged approach to reprogram the immune system—inhibition of critical pathways, activation of others, and depletion of malignant cells—may be the best strategy to optimize immune function in B-cell lymphomas, according to Stephen M. Ansell, MD, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“[A]ll told, there are multiple immunological barriers to an effective immune response,” Dr Ansell said at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2015.

“So the questions are how can you use an immune checkpoint approach to try and modulate this and improve the outcome.”

Dr Ansell discussed checkpoint inhibitors, immune signal activators, and the potential of combining the approaches in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in a way that enhances rather than antagonizes their effects.

Blocking CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) functions as an immune checkpoint that downregulates the immune system. A receptor found on the surface of inhibitor T cells, it acts as an off switch when it binds to CD80 or CD86 on the surface of antigen-presenting cells.

Ipilimumab, an antibody that targets CTLA-4, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of melanoma and is in clinical trials for lung, bladder, and prostate cancer.

Investigators wanted to see whether it also works in lymphoma, so they conducted a phase 1 study in relapsed/refractory B-cell NHL.

Eighteen patients received 3 mg/kg of ipilimumab. Two patients responded, 1 with a complete response (CR) that lasted more than 31 months, and 1 with a partial response (PR) that lasted 19 months. In 5 of 16 patients (31%), T-cell proliferation to recall antigens increased more than 2-fold.

As Dr Ansell explained, “Immune response doesn’t always correlate directly with the clinical responses. So I think we really have a lot to learn about what is really a biomarker of efficacy.”

Ipilimumab was also evaluated to treat relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in 29 patients with relapsed hematologic disease. Two patients with HL achieved a CR and 1 patient with mantle cell lymphoma achieved a PR.

The investigators observed that ipilimumab did not induce or exacerbate clinical graft-versus-host disease.

Blocking PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is a surface receptor expressed on T cells and pro-B cells. PD-1 binds 2 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2.

PD-1 ligands are overexpressed in inflammatory environments and attenuate the immune response through PD-1 on immune effector cells. In addition, PD-L1 expressed on malignant cells or in the tumor microenvironment suppresses tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte activity.

Pidilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to PD-1, weakens the apoptotic processes in lymphocytes and augments the antitumor activities of NK cells.

Investigators conducted a phase 2 trial of pidilizumab in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) after autologous HSCT to modulate the immune system after a transplant.

The team treated 66 patients with the antibody. At 16 months, progression-free survival (PFS) was 72%. For the 24 high-risk patients who were PET-positive after salvage chemotherapy, the 16-month PFS was 70%.

“And I think that what was most interesting,” Dr Ansell said, when focusing on the 35 patients with measurable disease after transplant, pidilizumab produced a 51% response rate “even in patients that actually had active disease.”

When pidilizumab was combined with rituximab in another trial in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL), 19 of 29 evaluable patients (66%) achieved an objective response: 15 (52%) CRs and 4 (14%) PRs.

“You might say, ‘Who cares? That’s not that great,’” Dr Ansell said. “But I think what was pretty impressive is that 52% CR rate. And most of you who treat patients with rituximab would know that that’s quite surprising, suggesting that there may be additional benefit for the use of PD-1 blockade in this subset of patients.”

Nivolumab, another monoclonal antibody that blocks the PD-1 pathway, is being investigated in a number of lymphoid malignancies, including HL, DLBCL, and T-cell lymphomas.

In a phase 1 study of nivolumab in 81 patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies, the best preliminary overall response has been in FL and DLBCL patients, with an objective response rate of 40% and 36%, respectively, including 1 PR and 3 PRs in each subtype.

“I think what is important,” Dr Ansell said, “is that the side effects, as expected, were mainly immune-mediated, not as dramatic as have been seen with other agents, and very similar to what has been seen in solid tumor studies.”

Dr Ansell pointed out that the response rates with nivolumab varied widely by histology, suggesting that “we have a lot to learn about why patients benefit and who exactly benefits.”

There were no responses in patients with multiple myeloma or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, although many patients achieved stable disease.

“Hodgkin lymphoma was completely different,” Dr Ansell said, “and there were responses in virtually every patient.”

Of 23 patients treated with nivolumab, 20 responded—4 achieved a CR and 16 a PR—including patients who had failed autologous HSCT and brentuximab vedotin treatment. Eleven patients, including 2 with CRs, have an ongoing response, some approaching 2 years. So the responses have been durable, Dr Ansell noted.

Yet another PD-1 antibody, pembrolizumab, has prompted reduction in tumor burden in HL in all but 2 of 29 evaluable patients, including 6 CRs and 13 PRs. The median duration of response has not yet been reached, and the side effect profile was similar to what has been seen with nivolumab and in solid tumors.

Activating immune stimulatory signals

Another approach to boosting the immune system is to activate immune stimulatory signals, eg, CD27 and CD40, and get a benefit that way. Varlilumab (CDX-1127) is an unconjugated monoclonal antibody that binds CD27 and activates CD27-expressing T cells.

In a phase 1 trial of varlilumab in 24 lymphoma patients, investigators found no significant depletion in absolute lymphocyte counts, T cells, or B cells. “Not quite the same success story,” Dr Ansell said, with a response—a CR—in only 1 patient.

Investigators did observe, however, evidence of increased soluble CD27, a reduction of circulating Tregs, and the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

And in a phase 1 study of the anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody dacetuzumab in recurrent NHL, “the response rate was disappointingly low,” Dr Ansell said.

Investigators observed 6 objective responses, including 1 CR and 5 PRs, and a decrease in tumor size in approximately one-third of the 50 patients treated.

The investigators of the subsequent phase 2 trial did not want to take the agent forward for further study, Dr Ansell noted, “but there are antibodies now being developed in this space that will hopefully be more effective and create a greater benefit.”

Optimizing immune function

Dr Ansell suggested there are 3 main approaches to treating patients. One is going directly after the malignant cells and depleting them. A second is to inhibit critical pathways that the malignant cell is dependent upon, “starving them, if you like.” The third way is to activate the immune system and thereby create a greater benefit for patients.

“[P]robably our best strategy is to use all 3 in a reprogram approach,” he said. “Because unless you target each one of these areas, the likelihood is that the other sides of the 3-legged stool will take over.”

“This is an encouraging and exciting time for immune checkpoints therapy and an encouraging and exciting time for immune therapies in general. I think this is really the new frontier in lymphomas.”