Background

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) conditions are characterized by abnormal respiratory patterns and abnormal gas exchange during sleep.1-3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common type of SDB, is characterized by repetitive episodes of airway narrowing during sleep that lead to respiratory disruption, hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation. In reproductive-aged women, epidemiologic studies suggest a 2% to 13% prevalence of OSA.4-6 Pregnancy is associated with changes that promote OSA, such as weight gain and edema of the upper airway.7 Frequent snoring, a common symptom of OSA, is endorsed by 15% to 25% of pregnant women.8-10 Health outcomes that have been linked to SDB in the nonpregnant population, such as hypertension and insulin-resistant diabetes, have clinically relevant correlates in pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes).11-13

The underlying mechanistic pathways linking SDB and adverse pregnancy outcomes are likely multifactorial. SDB leads to oxidative stress, autonomic dysfunction, inflammation, endothelial damage, and altered hormonal regulation of energy expenditure.14 These same biologic pathways have been linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes.15While several retrospective and cross-sectional studies suggest that SDB may increase the risk of developing hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes during pregnancy,16-18 up until recently, there were limited and conflicting data from prospective observational cohorts in which SDB exposure and pregnancy outcomes have been methodically measured and confounding variables carefully considered.19-21 Louis et al.19 reported on a cohort of 175 obese women and demonstrated that women with SDB (apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 5) were more likely to develop preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3, 9.9). However, two other small studies failed to demonstrate a positive association between SDB and pregnancy-related hypertension, but one suggested a relationship between SDB and gestational diabetes.20,21

Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy

The Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy (nuMoM2b-SDB) was a prospective cohort study.22,23 Level 3 home sleep tests were performed using a six-channel monitor that was self-applied by the participant twice during pregnancy, first between 60 and 150 weeks of pregnancy and then again between 220 and 310 weeks. An apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of at least 5 was used to define SDB. The study was powered to test the primary hypothesis that SDB occurring in pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes were rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, defined as preeclampsia and prenatal gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Adjustment covariates included maternal age (less than or equal to 21, 22-35, and over 35 years), body mass index (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2), chronic hypertension (yes, no), and, for midpregnancy, rate of weight gain per week between early and midpregnancy assessments, treated as a continuous variable.

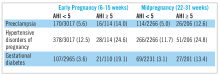

There were 3,705 women enrolled. AHI data were available for 3,132 (84.5%) and 2,474 (66.8%) women in early and midpregnancy, respectively. The corresponding prevalence of SDB was 3.6% and 8.3%. The overall prevalence of preeclampsia was 6.0%; hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, 13.1%; and gestational diabetes, 4.1%. In early and midpregnancy, the adjusted odds ratios for preeclampsia when SDB was present were 1.94 (95% CI, 1.07-3.51) and 1.95 (95% CI, 1.18-3.23), respectively; hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, 1.46 (95% CI, 0.91-2.32) and 1.73 (95% CI, 1.19-2.52); and gestational diabetes mellitus, 3.47 (95%, CI 1.95-6.19) and 2.79 (95% CI, 1.63-4.77). Additionally, increasing exposure-response relationships were observed between AHI and both hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes.23Conclusions and future directions

The nuMoM2b data are provocative because sleep apnea is a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. While a majority of SDB cases identified during pregnancy were mild, the nuMoM2b data demonstrate that even modest elevations of AHI in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders and an increased incidence of gestational diabetes.

Pregnancy is conceivably an ideal scenario in which to better understand the role of SDB treatment as a preventive strategy for reducing cardiometabolic morbidity as the time frame needed to measure incident outcomes after initiating therapy is significantly contracted. However, data regarding the role of OSA treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during pregnancy, both regarding its acceptability to patients and its therapeutic benefit, are extremely limited. Further research is needed to establish whether universal screening for and treating of SDB in pregnancy can mitigate the risks and consequences of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes. However, in the meantime, we have to recognize that as our obstetric patient population is becoming more obese, we will encounter more women with symptomatic SDB in pregnancy. It is well documented that patients with symptomatic SDB, those who report that their snoring leads to chronic sleep disruption and excessive daytime sleepiness, can benefit from CPAP in terms of sleep quality and daytime function. Therefore, in addition to encouraging women already prescribed CPAP to continue their therapy during pregnancy, obstetricians who encounter a patient reporting severe SDB symptoms should refer her to a sleep specialist for further evaluation.

Dr. Facco is assistant professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women’s Hospital, Magee Women’s Research Institute.

References

1. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597-619.

2. Park JG, Ramar K, Olson EJ. Updates on definition, consequences, and management of obstructive sleep apnea. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(6):549-54; quiz, 554-5.

3. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, Ill.: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

4. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14.

5. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-5.

6. Young T, Finn L, Austin D, Peterson A. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1181-5.

7. Pien GW, Schwab RJ. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1405-17.

8. Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV. Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):37-42.

9. Pien GW, Fife D, Pack AI, Nkwuo JE, Schwab RJ. Changes in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1299-1305.

10. Facco FL, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):77-83.

11. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-84.

12. Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521-30.

13. Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1590-5.

14. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47-112.

15. Romero R, Badr MS. A role for sleep disorders in pregnancy complications: Challenges and opportunities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):3-11.

16. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Pregnancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: Prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(6):487.e1-9

17. Chen YH, Kang JH, Lin CC, Wang IT, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):136.e1-5.

18. Bourjeily G, Raker CA, Chalhoub M, Miller MA, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(4):849-55.

19. Louis J, Auckley D, Miladinovic B, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with obstructive sleep apnea in obese pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1085-92.

20. Facco FL, Ouyang DW, Zee PC, et al. Implications of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;210(6):559.e1-6.

21. Pien GW, Pack AI, Jackson N, Maislin G, Macones GA, Schwab RJ. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Thorax. 2014;69(4):371-7.

22. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. NuMoM2b Sleep-Disordered Breathing study: Objectives and methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 April;212(4):542.e1–542.e127.

23. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. Association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertensive disorders of pregn ancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. ePub. 2016 Dec 2.