NEW ORLEANS – Both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio proved to be better predictors of the presence or absence of deep vein thrombosis than the ubiquitous D-dimer test in a retrospective study, Jason Mouabbi, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

What’s more, both the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) can be readily calculated from the readout of a complete blood count (CBC) with differential. A CBC costs an average of $16, and everybody that comes through a hospital emergency department gets one. In contrast, the average charge for a D-dimer test is about $231 nationwide, and depending upon the specific test used the results can take up to a couple of hours to come back, noted Dr. Mouabbi of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit.

“The NLR and PLR ratios offer a new, powerful, affordable, simple, and readily available tool in the hands of clinicians to help them in the diagnosis of DVT,” he said. “The NLR can be useful to rule out DVT when it’s negative, whereas PLR can be useful in ruling DVT when positive.”

Investigators in a variety of fields are looking at the NLR and PLR as emerging practical, easily obtainable biomarkers for systemic inflammation. And DVT is thought to be an inflammatory process, he explained.

Dr. Mouabbi presented a single-center retrospective study of 102 matched patients who presented with lower extremity swelling and had a CBC drawn, as well as a D-dimer test, on the same day they underwent a lower extremity Doppler ultrasound evaluation. In 51 patients, the ultrasound revealed the presence of DVT and anticoagulation was started. In the other 51 patients, the ultrasound exam was negative and they weren’t anticoagulated. Since the study purpose was to assess the implications of a primary elevation of NLR and/or PLR, patients with rheumatic diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, recent surgery, chronic renal or liver disease, inherited thrombophilia, infection, or other possible secondary causes of altered ratios were excluded from the study.

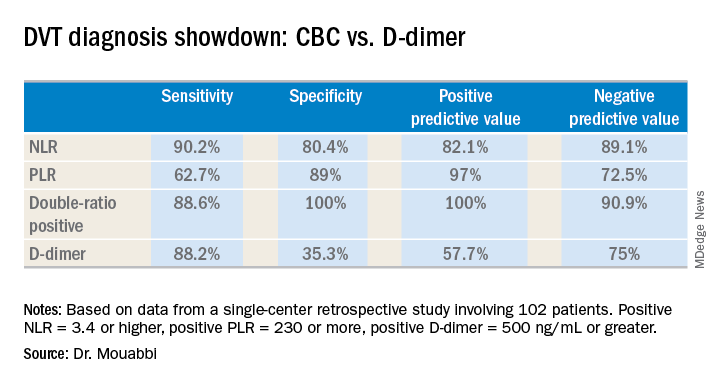

A positive NLR was considered 3.4 or higher, a positive PLR was a ratio of 230 or more, and a positive D-dimer level was 500 ng/mL or greater. The NLR and PLR collectively outperformed the D-dimer test in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

In addition, 89% of the DVT group were classified as “double-positive,” meaning they were both NLR and PLR positive. That combination provided the best diagnostic value of all, since none of the controls were double-positive and only 2% were PLR positive.

While the results are encouraging, before NLR and PLR can supplant D-dimer in patients with suspected DVT in clinical practice a confirmatory prospective study should be carried out, according to Dr. Mouabbi. Ideally it should include the use of the Wells score, which is part of most diagnostic algorithms as a preliminary means of categorizing DVT probability as low, moderate, or high. However, the popularity of the Wells score has fallen off in the face of reports that the results are subjective and variable. Indeed, the Wells score was included in the electronic medical record of so few participants in Dr. Mouabbi’s study that he couldn’t evaluate its utility.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.