like those on vivid display during the COVID-19 pandemic.

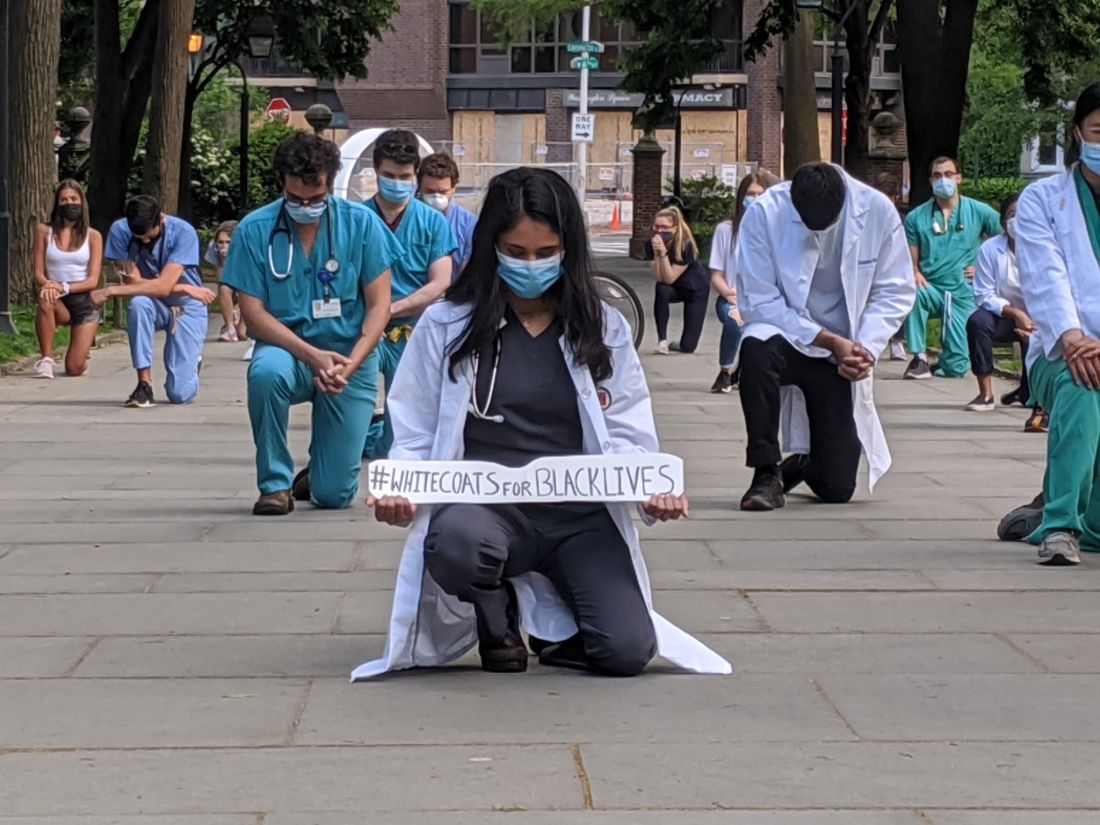

Sporadic protests – with participants in scrubs or white coats kneeling for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in memory of George Floyd – have quickly grown into organized, ongoing, large-scale events at hospitals, medical campuses, and city centers in New York, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Austin, Houston, Boston, Miami, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Albuquerque, among others.

The group WhiteCoats4BlackLives began with a “die-in” protest in 2014, and the medical student–run organization continues to organize, with a large number of protests scheduled to occur simultaneously on June 5 at 1:00 p.m. Eastern Time.

“It’s important to use our platform for good,” said Danielle Verghese, MD, a first-year internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, who helped recruit a small group of students, residents, and pharmacy school students to take part in a kneel-in on May 31 in the city’s Washington Square Park.

“As a doctor, most people in society regard me with a certain amount of respect and may listen if I say something,” Dr. Verghese said.

Crystal Nnenne Azu, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Indiana University, who has long worked on increasing diversity in medicine, said she helped organize a march and kneel-in at the school’s Eskenazi Hospital campus on June 3 to educate and show support.

Some 500-1,000 health care providers in scrubs and white coats turned out, tweeted one observer.

“Racism is a public health crisis,” Dr. Azu said. “This COVID epidemic has definitely raised that awareness even more for many of our colleagues.”

Disproportionate death rates in blacks and Latinos are “not just related to individual choices but also systemic racism,” she said.

The march also called out police brutality and the “angst” that many people feel about it, said Dr. Azu. “People want an avenue to express their discomfort, to raise awareness, and also show their solidarity and support for peaceful protests,” she said.

A June 4 protest and “die-in” – held to honor black and indigenous lives at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences campus in Albuquerque – was personal for Jaron Kee, MD, a first-year family medicine resident. He was raised on the Navajo reservation in Crystal, New Mexico, and has watched COVID-19 devastate the tribe, adding insult to years of health disparities, police brutality, and neglect of thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women, he said.

Participating is a means of reassuring the community that “we’re allies and that their suffering and their livelihood is something that we don’t underrecognize,” Dr. Kee said. These values spurred him to enter medicine, he said.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, who also attended the “die-in,” said she hopes that peers, in particular people of color, see that they have allies at work “who are committed to being anti-racist.”

It’s also “a statement to the community at large that physicians and other healthcare workers strive to be anti-racist and do our best to support our African American and indigenous peers, students, patients, and community members,” she said.