VIENNA – The new European recommendations for diagnosing and treating hepatitis C infection highlight the paradox gripping the field: Safe and potent antiviral drugs are available to cure most patients after 12 weeks of treatment, but cure is not broadly available because the agents are prohibitively expensive.

“Virtually everyone infected by hepatitis C virus [HCV] has the right to be treated,“ Dr. Jean-Michel Pawlotsky said during a session at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) that introduced the association’s new hepatitis C treatment recommendations.

The recommendations, released online around the time of the meeting, say: “Because of the approval of highly efficacious new HCV treatment regimens, access to therapy must be broadened.” In addition, they call for expanded screening to find more of the many unidentified cases of chronic hepatitis C infection (J. Hepatology 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025]). “However, we also have to acknowledge the reality that these drugs are currently too expensive, and the huge number of patients with HCV infection makes it impossible that we could treat all infected patients over the next couple of years,” said Dr. Pawlotsky, head of the department of virology at the Henri Mondor University Hospital in Créteil, France.

The prioritization scheme the EASL panel published gives highest treatment priority to patients with F3 or F4 liver fibrosis on the Metavir scoring system, HIV- or hepatitis B virus–coinfected patients, liver transplant candidates or recent recipients, and patients with significant extrahepatic manifestations, debilitating fatigue, or a high risk for transmitting infection. The list puts patients with moderate liver fibrosis, with a Metavir score of F2, a step down in priority but still rates them candidates for treatment. But the prioritization table rates patients with F1 or F0 fibrosis and none of the other stated complications as reasonable for deferred treatment.

This approach, as well as the general scheme recommended for drug selection, is “remarkably similar” to the guidance first issued and then revised last year by experts assembled by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, commented Dr. Donald M. Jensen, a hepatologist in Oak Park, Ill., who helped draft the U.S. guidance. “The more these two guidelines are consistent, the more powerful they are,” Dr. Jensen said as an invited discussant at the session.

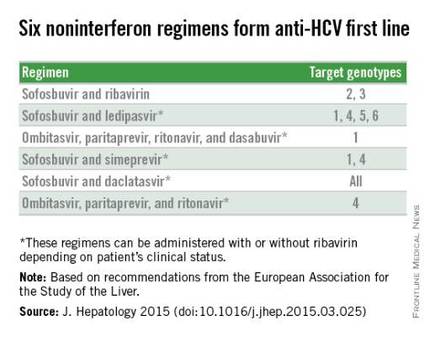

Perhaps the biggest difference between the HCV treatment recommendations from the European and American groups is that the EASL document included daclatasvir (Daklinza), a direct-acting antiviral for HCV that became available for use in Europe in 2014, but which remains under Food and Drug Administration review for U.S. use as of May 2015.

With daclatasvir as an option, the EASL panel highlighted six HCV regimens as first-line HCV options that all avoid treatment with interferon. The recommendations further fine-tune the options from this list of six regimens depending on the infecting HCV genotype, as well as special clinical situations such as compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, recent liver transplant, or end-stage renal disease. The EASL panel also firmly relegated interferon-containing regimens to second-line status.

Another significant issue in choosing among HCV treatments are drug-drug interactions. The EASL panel endorsed a website maintained by the University of Liverpool (England) as an excellent source for researching drug-interaction issues, Dr. Pawlotsky said.