THE CLINICAL WORK-UP: PUTTING KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE

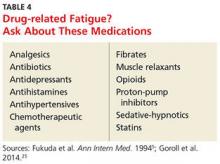

Familiarity with potential causes of and connections with ME/CFS will help you ensure that patients who say they’re always tired receive a thorough work-up. Start with a medical history, inquiring directly about medical and psychiatric disorders that may contribute to fatigue (see Table 3).5,24,25 Include a medication history as well, to help determine whether the fatigue is drug-related (see Table 4).5,25

What to ask. Determine the onset, course, duration, daily pattern, and impact of fatigue on the patient’s daily life. Inquire, too, about related symptoms of daytime sleepiness, dyspnea on exertion, generalized weakness, and depressed mood. The prominence of any of these rather than fatigue, per se, point to a diagnosis of a chronic illness other than ME/CFS.

Keep in mind, too, that patients with an organ-based medical illness tend to associate their fatigue with activities that they are unable to complete, such as shopping or light housework. In contrast, those with fatigue that is not organ-based typically say that they’re tired all the time. Their fatigue is not necessarily related to exertion, nor does it improve with rest.26

To address this distinction, take a sleep history, assessing both the quality and quantity of the patient’s sleep to determine how it affects symptoms.27 Consider using a questionnaire designed to help distinguish between sleepiness—and a primary sleep disorder—and fatigue,28 such as the Fatigue Severity Scale of Sleep Disorders (www.healthywomen.org/sites/default/files/FatigueSeverityScale.pdf).

What to rule out. In addition to a medical history, the physical examination should be oriented toward ruling out secondary causes of fatigue. In addition to a system-by-system approach to the differential diagnosis, carefully observe the patient’s general appearance, with attention to his or her level of alertness, grooming, and psychomotor agitation or retardation as possible signs of a psychiatric disorder. To rule out neurologic causes, evaluate muscle bulk, tone, and strength; deep tendon reflexes; and sensory and cranial nerves, as well.29

Lab tests to consider. In most cases of ME/CFS, basic studies—complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood chemistry, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels—are sufficient. When no medical or psychiatric cause has been found, additional tests may be ordered on a case-by-case basis, although laboratory analysis affects the management of fatigue in less than 5% of such patients.30 Tests to consider include:

• Creatine kinase (for patients who report pain or muscle weakness)

• Pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age)

• Ferritin testing (for young women who might benefit from iron supplementation for levels < 50 ng/mL even if anemia is not present)31

• Hepatitis C screening (recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force for those born between 1945 and 1965)32

• HIV screening and the purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis (based on patient history).

Forego routine testing for other infections

Routine testing for infectious diseases and conditions associated with fatigue, such as EBV or Lyme disease, immune deficiency (eg, immunoglobulins), inflammatory disease (eg, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor), celiac disease, vitamin D deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, or heavy metal toxicity, is unlikely to be helpful.29 Additional testing simply to reassure a worried patient usually does not accomplish that objective.33

Additional studies, referrals to consider. If you suspect that a patient has a sleep disorder, a referral to a sleep clinic to rule out idiopathic sleep disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, or movement disorders that interfere with sleep may be in order. Spirometry and echocardiography may be helpful for some patients. If you suspect peripheral muscle fatigue, a referral for neuromuscular testing is indicated.

Lauren’s medical history reveals that she also has irritable bowel syndrome, which she manages with diet and OTC medication, as needed for constipation or diarrhea. She denies having any other chronic conditions. Her only other symptoms, she reports, are mild upper back pain after spending long hours at the computer and arthralgias in her left knee and both hands. She admits to being “somewhat depressed” in the last few months but denies the presence of anhedonia.

The patient’s physical examination is normal, and her depression screen does not meet the criteria for MDD. Her metabolic chemistry panel, complete blood count, TSH, and sedimentation rate are all normal, as well.

Continue for symptom management and coping strategies >>