Humans usually become infected from May through August, when both they and the nymph ticks are most active outdoors. The ticks are able to attach themselves to their host without being noticed because they secrete small amounts of saliva with anesthetic properties while feeding. Many ticks also secrete a cement-like substance that keeps them firmly attached.

Adult ticks can also transmit the disease and are larger and more easily recognized. Transmission of the spirochete requires that the tick be attached to the new host for 36 to 48 hours,1 allowing the spirochete to travel from the mid-gut of the tick to the salivary glands and into the host.

Two of the most important factors to consider when assessing the risk of transmission is how long the tick was attached and whether it was engorged. Only about a quarter of individuals with Lyme disease recall having had a tick bite.1,3-6,8

Clinical presentation: Early and late findings

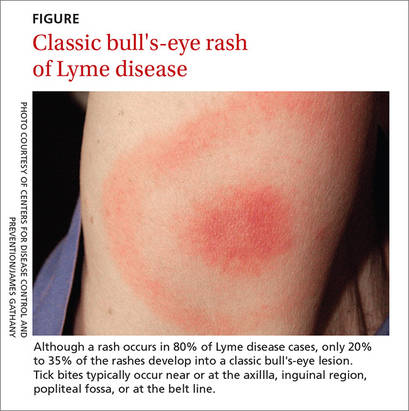

Symptoms of early Lyme disease usually start one to 2 weeks after a tick bite, but may start up to 30 days later. The most common presentation is a painless skin rash—erythema migrans (EM). It starts as a single red papule at the site of the bite (multiple lesions appear in 10% to 20% of cases9) and may progress to a painless erythematous lesion with red borders and a partial central clearing—the classic EM rash (FIGURE). Less commonly, the center of the lesion can appear vesicular or necrotic.

Although a rash occurs in 80% of Lyme disease cases, only 20% to 35% of the rashes develop into a classic bull's-eye lesion.3 Tick bites—and thus rashes—typically occur near or at the axilla, inguinal region, popliteal fossa, or at the belt line.

Individuals who don’t exhibit a rash may be asymptomatic or have nonspecific symptoms or flu-like symptoms of fatigue, fever, chills, myalgia, and headache.4 If Lyme disease continues untreated, the patient may experience extra-cutaneous complications, most often involving the joints and the nervous and cardiovascular systems.3-7