The discomfort caused by an urticarial rash, along with its unpredictable course, can interfere with a patient’s sleep and work/school. Adding to the frustration of patients and providers alike, an underlying cause is seldom identified. But a stepwise treatment approach can bring relief to all.

Urticaria, often referred to as hives, is a common cutaneous disorder with a lifetime incidence between 15% and 25%.1 Urticaria is characterized by recurring pruritic wheals that arise due to allergic and nonallergic reactions to internal and external agents. The name urticaria comes from the Latin word for “nettle,” urtica, derived from the Latin word uro, meaning “to burn.”2

Urticaria can be debilitating for patients, who may complain of a burning sensation. It can last for years in some and reduces quality of life for many. Recently, more successful treatments for urticaria have emerged that can provide tremendous relief.

It is important to understand some of the ways to diagnose and treat patients in a primary care setting and also to know when referral is appropriate. This article will discuss the diagnosis, treatment, and referral process for patients with chronic urticaria.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hives most commonly arise from an immunologic reaction in the superficial skin layers that results in the release of histamine, which causes swelling, itching, and erythema. The mast cell is the major effector cell in the pathophysiology of urticaria.3 In immunologic urticaria, the antigen binds to immunoglobulin (Ig) E on the mast cell surface, causing degranulation and release of histamine, which accounts for the wheals and itching associated with the condition. Histamine binds to H1 and H2 receptors in the skin to cause arteriolar dilation, venous constriction, and increased capillary permeability, accounting for the accompanying swelling.3 Not all urticaria is mediated by IgE; it can result from systemic disease processes in the body that are immune related but not related to IgE. An example would be autoimmune urticaria.

Urticaria commonly occurs with angioedema, which is marked by a greater degree of swelling and results from mast cell activation in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Either condition can occur independently, however. Angioedema typically affects the lips, tongue, face, pharynx, and bilateral extremities; rarely, it affects the gastrointestinal tract. Angioedema may be hereditary, but its nonhereditary causes can be similar to those of urticaria.3 For example, a patient could be severely allergic to cat dander and, when exposed to this allergic trigger, develop swelling of the lips, facial edema, and flushing.

FORMS OF URTICARIA

Urticaria can be broadly divided based on the duration of illness: less than six weeks is termed acute urticaria, and continuous or intermittent presence for six weeks or more, chronic urticaria.4

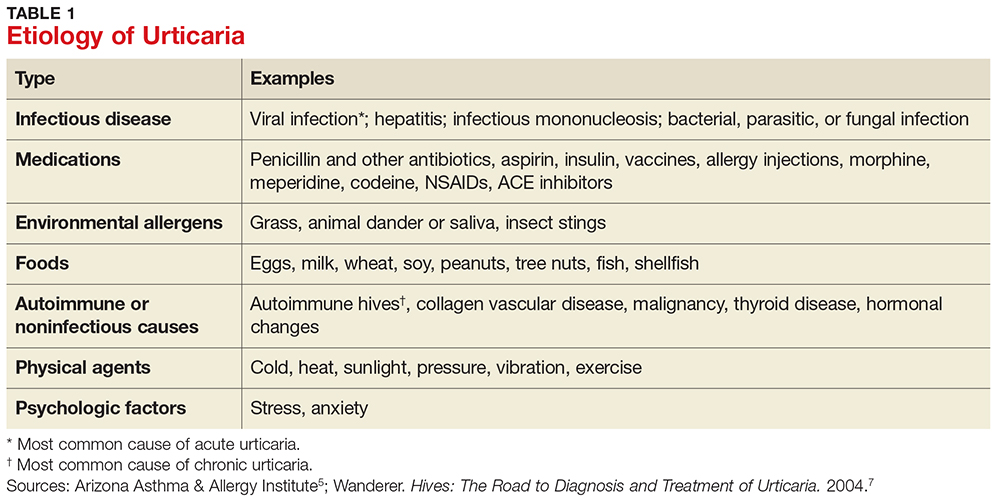

Acute urticaria may occur in any age group but is most often seen in children.1 Acute urticaria and angioedema frequently resolve within a few days, without an identified cause. An inciting cause can be identified in only about 15% to 20% of cases; the most common cause is viral infection, followed by foods, drugs, insect stings, transfusion reactions, and, rarely, contactants and inhalants (see Table 1).1,5 Acute urticaria that is not associated with angioedema or respiratory distress is usually self-limited. The condition typically resolves before extensive evaluation, including testing for possible allergic triggers, can be done. The associated skin lesions are often self-limited or can be controlled symptomatically with antihistamines and avoidance of known possible triggers.1

Chronic urticaria, sometimes called chronic idiopathic urticaria, is more common in adults, occurs on most days of the week, and, as noted, persists for more than six weeks with no identifiable triggers.6 It affects about 0.5% to 1% of the population (lifetime prevalence).3 Approximately 45% of patients with chronic urticaria have accompanying episodes of angioedema, and 30% to 50% have an autoimmune process involving autoantibodies against the thyroid, IgE, or the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcR1).3 The diagnosis is based primarily on clinical history and presentation; this will guide the determination of what types of diagnostic testing are necessary.

Chronic urticaria requires an extensive, but not indiscriminate, evaluation with history, physical examination, allergy testing, and laboratory testing for immune system, liver, kidney, thyroid, and collagen vascular diseases.3 Unfortunately, an identifiable cause of chronic urticaria is found in only 10% to 20% of patients; most cases are idiopathic.3,7

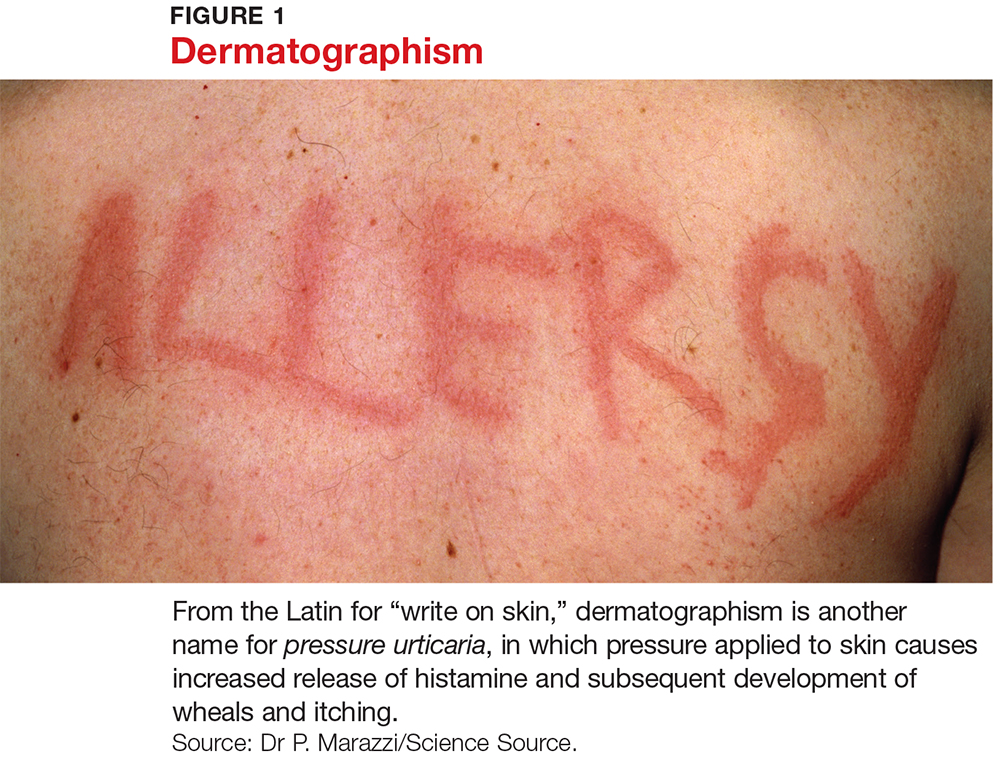

Several forms of chronic urticaria can be precipitated by physical stimuli, such as exercise, generalized heat, or sweating (cholinergic urticaria); localized heat (localized heat urticaria); low temperatures (cold urticaria); sun exposure (solar urticaria); water (aquagenic urticaria); and vibration.1 In another form (pressure urticaria), pressure on the skin increases histamine release, leading to the development of wheals and itching; this form is also called dermatographism, which means “write on skin” (see Figure 1). These types of urticaria should be evaluated and treated by a board-certified allergist, as there are special evaluations that can confirm the diagnosis.