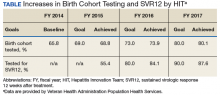

Each year, teams worked toward achieving goals set nationally. These included increasing HCV birth cohort testing and improving the percentage of patients who had SVR12 testing

(Table).

the percentage of patients who received SVR12 testing posttreatment completion was not included in the HIT Collaborative’s annual goals for the first year of the program. Recognizing this as a critical area for improvement, the HIT CLT set a goal to test 80% of all patients who completed treatment. The HITs applied Lean tools to identify and overcome gaps in the SVR12 testing process. By the end of the second year, 84% of all patients who completed treatment had been tested for SVR12.

The HITs also set specific local VISN and medical center goals, prioritizing projects that could have the greatest impact on local patient access and quality of care and build on existing strengths and address barriers. These projects encompass a wide range of areas that contribute to the overall national goals.

Focus on Lean

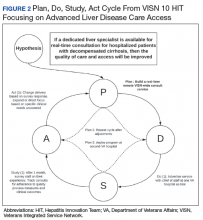

Lean process improvement is based on 2 key pillars: respect for people (those seeking service as customers and patients and those providing service as frontline staff and stakeholders) and continuous improvement. With Lean, personnel providing care should work to identify and eliminate waste in the system and to streamline care delivery to maximize process steps that are most valued by patients (eg, interaction with a clinical provider) and minimize those that are not valued (eg, time spent waiting to see a provider). With the knowledge that HHRC fully supports their work, HITs were encouraged to innovate based on local resources, context, and culture.

Teams receive basic training in Lean from the HIT CLT and local systems redesign specialists if available. The HITs apply the A3 structured approach to problem solving. 11 The HITs follow prescribed problemsolving steps that help identify where to focus process improvement efforts, including analyzing the current state of care, outlining the target state, and prioritizing solution

approaches based on what will have the highest impact for patients.

to accommodate the outcomes they observe (Figure 2).

Innovations

Over the course of the HIT Collaborative, numerous innovations have emerged to address and mitigate barriers to HCV screening and treatment. Examples of successful innovations include the following:

- To address transportation issues, several teams developed programs specific to patients with HCV in rural locations or with limited mobility. Mobile vans and units traditionally used as mobile cardiology clinics were transformed into HCV clinics, bringing testing and treatment services directly to veterans;

- Pharmacists and social workers developed outreach strategies to locate homeless veterans, provide point-of-care testing and utilize mobile technology to concurrently enroll and link veterans to care; and

- Many liver care teams partnered with inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment clinics to provide patient education and coordinate HCV treatment.

Inter-VISN working groups developed systemwide tools to address common needs. In the program’s first year, a few medical facilities across a handful of VISNs shared local population health management systems, programming, and best practices. Over time, this working group combined the virtual networking capacity of the HIT Collaborative with technical expertise to promote rapid dissemination and uptake of a population health management system. Providers at medical centers across VA use the tools to identify veterans who should be screened and treated for HCV with the ability to continuously update information, identifying patients who do not respond to treatment or patients overdue for SVR12 testing.

Providers with experience using telehepatology formed another inter-VISN working group. These subject matter experts provided guidance to care teams interested in implementing telehealth in areas where limited local resources or knowledge had prevented them from moving forward. The ability to build a strong coalition across content areas fostered a collaborative learning environment, adaptable to implementing new processes and technologies.

In 2017, the VA made significant efforts to reach out to veterans eligible for VA care who had not yet been screened or remained untreated. In May, Hepatitis Awareness Month, HITs held HCV testing and community outreach events and participated in veteran stand-downs and veteran service organization activities.

National and local advertising campaigns promoted HCV services at the VA on television, radio, and in print publications and through social media (eFigure)Evaluation

Since 2014, the VA has increased its HCV treatment and screening rates. To assess the components contributing to these achievements and the role of the HIT Collaborative in driving this success, a team of implementation scientists have been working with the CLT to conduct a HIT program evaluation. The goal of the evaluation is to establish the impact of the HIT Collaborative. The evaluation team catalogs the activities of the Collaborative and the HITs and assesses implementation strategies (use of specific techniques) to increase the uptake of evidence-based practices specifically related to HCV treatment. 12

At the close of each FY, HCV providers and members of the HIT Collaborative are queried through an online survey to determine which strategies have been used to improve HCV care and how these strategies were associated with the HIT Collaborative. The use of more strategies was associated with more HCV treatment initiations. 13 All utilized strategies were identified whether or not they were associated with treatment starts. These data are being used to understand which combinations of strategies are most effective at increasing treatment for HCV in the VA and to inform future initiatives.

Expanding the Scope

Inspired by the successful results of the HIT work in HCV and in the spirit of continuously improving health care delivery, HHRC expanded the scope of the HIT Collaborative in FY 2018 to include ALD. There are about 80,000 veterans in VA care with advanced scarring of the liver and between 10,000 to 15,000 new diagnoses each year. In addition to HCV as an etiology for ALD, cases of cirrhosis are projected to increase among veterans in care due to metabolic syndrome and alcohol use. A recent review of VA data from fiscal year 2016 found that 88.6% of ALD patients had been seen in primary care within the past 2 years, with about half (51%) seen in a gastroenterology (GI) or hepatology clinic (Personal communication, HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Program Office March 16, 2018). For patients in VA care with ALD, GI visits are associated with a lower 5-year mortality.14 Annual mortality for all ALD patients in VA is 6.2%, and of those with a hospital admission, mortality rises to 31%.15 In FY 2016, there were about 52,000 ALD-related discharges (more than 2 per patient). Of those discharges, 24% were readmitted within 30 days, with an average length of stay of 1.9 days and an estimated cost per patient of $47,000 over 3 years. 16

Hepatologists from across the VA convened to identify critical opportunities for improvement for patients with ALD. Base on available evidence presented in the literature and their clinical expertise, these subject matter experts identified several areas for quality improvement, with the overarching goal to improve identification of patients with early cirrhosis and ensure appropriate linkage to care for all cirrhotic patients, thus improving quality of life and reducing mortality. Although not finalized, candidate improvement targets include consistent linkage to care and treatment for HCV and HBV, comprehensive case management, post-discharge patient follow-up, and adherence to evidence-based standards of care.

Conclusion

The VA has made great strides in nearly eliminating HCV among veterans in VA care. The national effort to redesign hepatitis care using Lean management strategies and develop local and regional teams and centralized support allowed VA to maximize available resources to achieve higher rates of HCV birth cohort testing and treatment of patients infected with HCV than has any other health care system in the US.

The HIT Collaborative has been a unique and innovative mechanism to promote directed, patient-outcome driven change in a large and dynamic health care system. It has allowed rural and urban providers to work together to develop and spread quality improvement innovations and as an integrated system to achieve national priorities. The focus of this foundational HIT structure is expanding to identifying, treat, and care for VA’s ALD population.