If the more common form of endometriosis is frequently missed, this rarely seen variant presents an even greater diagnostic challenge. The typical presentation of inguinal endometriosis includes a firm nodule in the groin, accompanied by tenderness and swelling. A careful history will allude to pain that occurs cyclically with menses.

Cause

Among several theories about the etiology of endometriosis, the most popular has been retrograde menstruation.1,4,5 According to this hypothesis, the flow of menstrual blood moves backward through the fallopian tubes, spilling into the pelvic cavity and carrying endometrial tissue with it. One theory purports that endometrial tissue is transplanted from the uterus to other areas of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatics, much like a metastatic disease.1,4 Another theory states that cells outside the uterus, which line the peritoneum, transform into endometrial cells through metaplasia.4,5 Endometrial tissue can also be transplanted iatrogenically during surgery—for example, when endometrial tissue is displaced during a cesarean delivery, resulting in implants above the fascia and below the subcutaneous layers. Several other hypotheses concern stem-cell involvement, hormonal factors, immune system dysfunction, and genetics.4,5 Currently, there are no definitive answers.

Location

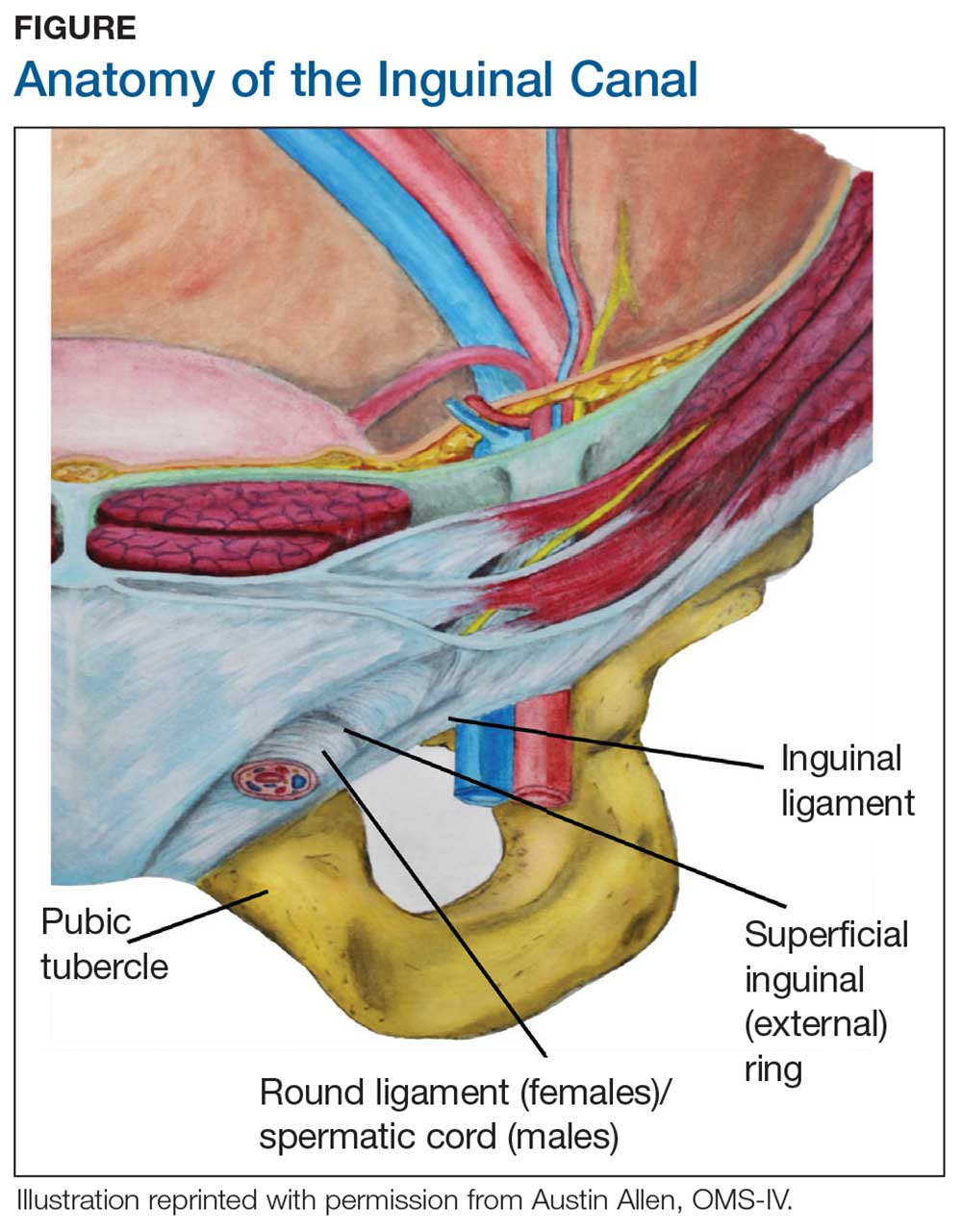

During maturation, the parietal peritoneum develops a pouch called the processus vaginalis, which serves as a passageway for the gubernaculum to transport the round ligament running from the uterus, through the inguinal canal, and ending at the labia. After these structures reach their destination, in normal development, the processus vaginalis degenerates, closing the inguinal canal. Occasionally the processus vaginalis fails to close, allowing for a communication pathway between the peritoneal cavity and the inguinal canal. This leaves the canal vulnerable to the contents of the pelvic cavity, such as a hernia or hydrocele, and provides a clear path for endometriosis.5-7 The implant found in the case patient was at the point where the external ring lies, just above the right pubic tubercle (see Figure 1).

Endometriosis implants can occur anywhere along the round ligament in either the intrapelvic or extrapelvic segments. Implants have also been found in the wall of a hernia sac, the wall of a Nuck canal hydrocele, or even in the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the inguinal canal.3 Interestingly, inguinal endometriosis occurs more often in the right side (up to 94% of cases) than in the left side, as was the case with our patient.5-7 The reason for this predominance has not been established, although there are several theories, including one that suggests the left side is afforded protection by the sigmoid colon.5-7

Laboratory diagnosis

Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, offers some diagnostic benefit, although its usefulness is most often realized in the pelvis. Pelvic ultrasound can be used to identify ovarian endometriomas.1 MRI can help rule out, locate, or sometimes determine the degree of deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is an indispensable tool for surgical planning.5,7 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy for extra-pelvic lesions is variable; neither modality is particularly useful in identifying superficial lesions, which comprises most cases.