At age 27, a woman with no family history of hypertension was diagnosed with the disease, which was left untreated. Two years later—during her first pregnancy—she was still hypertensive and was prescribed methyldopa, which was switched to lisinopril in the postpartum period. Her blood pressure (BP) remained elevated, despite titration of lisinopril and the addition of a β-blocking agent.

In the same year, the woman went to the emergency department with a severe headache and near-syncope; her BP was 180/100 mm Hg. Her medications were changed, and she was discharged with a prescription for captopril 50 mg bid and the angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) valsartan 80 mg bid. Over the following six years, her average BP remained around 140/90 mm Hg with no further medication adjustment.

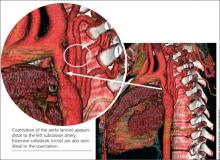

When the patient was 37, she underwent a chest x-ray (CXR), prompted by positive results on a purified protein derivative test at an employment physical; the CXR demonstrated a 3.6-cm mediastinal mass. This finding led to a chest CT exam that demonstrated a severe coarctation distal to the left subclavian artery with diffuse tubular hypoplasia, a collateral reconstitution of the descending aorta, and a true 2.7-cm aneurysm of one of the intercostal arteries.

The gradient between the ascending and descending aorta was 50 mm Hg, and the same wide pressure gradient was present between the upper and lower extremities (50 mm Hg).

Referral to pediatric cardiology was initiated. (It is not uncommon for an adult with a congenital heart lesion to be evaluated by a pediatric cardiologist in centers where adult congenital heart disease [ACHD] specialists are not available.) A cardiac MRI revealed a virtual interruption of the aortic arch in juxta-ductal position with multiple aortic collateral arteries. Subsequent cardiac catheterization demonstrated a transverse aortic arch at 1.2 cm and a narrowing to 7 mm just distal to the left subclavian artery, with a discrete coarctation of 2.5 mm.

With hypertension and a 50–mm Hg resting clinical gradient, corrective treatment was deemed necessary. Subsequently, balloon angioplasty was performed, and a drug-eluting stent was placed in the proximal distal aorta with dilation of the narrowing and a resultant decrease in BP gradient from 50 mm Hg to 7 mm Hg. Following stent placement, the aneurysm thrombosed secondary to reduced blood flow. Clinical reevaluation showed good dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses with improved BP. The ARB was subsequently discontinued, and the patient continued to take captopril for mildly elevated BP (average, 130/85 mm Hg).

The patient did well until three years later, when she developed shortness of breath on exertion, claudication, and fatigue for a period of two weeks. On physical examination, her BP was noted to be elevated at 140/90 mm Hg with a clinical gradient of 20 mm between the upper and lower extremities and an increase in the gradient on echocardiogram to a peak of approximately 46 mm Hg and a mean of 21 mm Hg.

A subsequent chest CT demonstrated a narrowing of the previous stent site, and a right and left cardiac catheterization revealed neo-intimal proliferation affecting the stent with a 3–mm Hg gradient across the transverse arch and a 15–mm Hg gradient across the proximal descending aorta stent. The stent was subsequently redilated, and an additional stent was placed with no residual gradient.

The patient was discharged while taking clopidogrel 75 mg/d in addition to aspirin 325 mg/d for six months; antihypertensive medications were no longer necessary. Clinical evaluation with echocardiography was recommended every three months for the first year, and annually thereafter. At three-month and one-year follow-up, the patient was found to be symptom-free and normotensive (BP, 110/70 mm Hg).

DISCUSSION

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a discrete narrowing of the thoracic aorta at the junction of the ductus arteriosus and the aortic arch, just distal to the subclavian artery. The specific anatomy, severity, and degree of hypoplasia proximal to the aortic coarctation are highly variable. For example, in some instances, coarctation presents as a long segment or a tubular hypoplasia.1

The defect is often associated with other congenital cardiovascular abnormalities, including bicuspid aortic valve (BAV; reported incidence, up to 85%),2,3 intracranial aneurysms (incidence, 3% to 10%),4 intrinsic abnormality in the aorta, aortic arch hypoplasia, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, aortic stenosis at different levels (valvular, subvalvular, or supravalvular), and mitral valve abnormalities.2,5 There is evidence of increased familial risk for CoA and increased prevalence with certain disorders, including Turner syndrome, maternal phenylketonuria syndrome, and Kabuki syndrome.6

CoA accounts for 5% to 8% of all congenital heart disease,2,3 and its incidence is 4 in 10,000 births.1 (Adults presenting with CoA represent either recoarctation or a missed diagnosis of native coarctation.) The mean life expectancy of untreated patients with aortic coarctation is 35 years; 90% die before age 50.1