An observation of unusually sexualized behaviors or a report of excessive masturbation is more likely to be associated with sexual abuse than are genital findings (which are infrequently found).

Physical Examination

When a child presents with an acute injury or bruising is detected and the clinician’s findings are inconsistent with the given history, suspicion should be raised. The injuries inflicted by physical abuse are often hidden beneath the child’s clothing (specifically, underwear); for this reason, it is important to have children undressed during a physical exam.

The routine physical exam of an abused child may reveal defensive bruising or other wounds, trauma to the mouth, breasts, buttocks, genitalia, or anus, with possible bleeding or discharge. More commonly, the physical exam findings are normal—as is true in the majority of examinations for sexual abuse.30 In one large study, abnormal findings (eg, recent or healed genital injuries; presence of a sexually transmitted disease) were found in only about 4% of children who had been referred for an examination for suspected sexual abuse.18,31 Clearly, an appearance of “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”32

According to CDC guidelines,33 investigation of suspected sexual abuse (for example, when a genital herpes infection is detected) should be conducted by appropriately trained, experienced clinicians—ideally, by a pediatric subspecialist in child abuse. Although the primary care clinician may examine the child briefly for visible bruises or wounds, it is essential for a specialist to perform the genital exam.33 Use of mild sedation with close monitoring may be advisable during the genital examination.30

Mimics of Child Abuse

Several conditions, including metabolic, genetic, and congenital disorders, have been reported to mimic the physical manifestations of child abuse and neglect17,22,34 (see Table 4,17,18,22,25,33-35). While health care professionals are legally and ethically bound to report abuse, conditions that may mimic abuse must be ruled out first, to avoid the mistaken removal of children from loving homes.

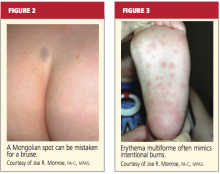

Mongolian spots, for example (see Figure 2), are frequently mistaken for bruising and reported to authorities, causing unnecessary disruption for both family and child.34,36 They typically appear as macular blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, usually on the sacrum. Resulting from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during fetal development, these “spots” may be present at birth or may appear during the neonatal period. Mongolian spots are most common in Native American, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic patients, are benign, and often disappear by age 4.

Other cutaneous manifestations that can mimic an intentional injury include molluscum contagiosum, a viral infection manifesting as a rash that may mimic the genital warts of human papillomavirus, and erythematous, edematous, and/or vesiculobullous lesions18,35 (see Figure 3). Severe diaper rash, photodermatitis, and certain allergic reactions can mimic intentional burns.25

Often mistaken for a nonaccidental injury is hair tourniquet syndrome—the circumferential strangulation of one or more appendages (eg, finger, toe, penis) by human hair or fibers.34 This uncommon condition, usually unintentional and of unknown incidence, can represent a surgical emergency; failure to recognize it in a timely fashion may lead to ischemia or necrosis, necessitating amputation of the affected appendage.37

Metabolic bone disease, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, can sometimes explain frequent fractures.17

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

In the primary care setting, the detection of child abuse is unexpected. However, it is often here that children are initially seen for an injury, or suspicions are raised during a routine physical.30 In the case of spontaneous disclosure of abuse, explicit, word-for-word documentation is required. The child, who may feel guilty, embarrassed, or ashamed, must be reassured that he or she is not at fault.

Either a child abuse specialist or the primary care clinician bases the ultimate diagnosis of child abuse on findings from the history and physical examination. These findings will direct the clinician’s decision to order diagnostic laboratory studies and/or diagnostic x-rays.

Diagnostic Studies

Depending on the child’s age and the type of presentation, recommended imaging studies include an x-ray skeletal survey of a child younger than 2 (see “Skeletal Survey Reading of 5-Month-Old Boy,”) or an older child with thoracoabdominal injuries that the history does not explain satisfactorily.23 For children ages 2 to 5, focused plain films of the area of suspected injury (eg, skull, chest, extremities) are considered appropriate.23,38

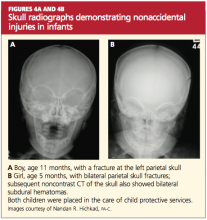

Noncontrast head CT may be appropriate in the presence of skull fractures, (as in Figures 4a and 4b) intracranial injuries, seizures, or other neurologic signs and symptoms (followed by MRI if further assessment is needed). CT with contrast may be considered when x-rays reveal certain abnormalities, the child is considered at high risk for abuse (for example, when inconsistencies are found in the history), or when soft-tissue injuries are suspected.23,39