Reported incidence rates of certain vaccine-preventable diseases—measles, rubella, diphtheria, polio, and tetanus—are low in the United States.1 However, as was demonstrated during the 2009-2010 flu season and the outbreak of H1N1 influenza,2 we cannot afford to be complacent in our attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination. New virus strains exist and can become endemic quickly and ravenously. Furthermore, certain vaccine-preventable illnesses are frequently reported among adult patients, including hepatitis B, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus infection, influenza, pertussis, and pneumococcal infection.3

Vigilance regarding vaccination of children and adults was addressed by the CDC’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion in Healthy People 2010.4 These target objectives are proposed to be retained in Healthy People 2020,5 as the objectives from 2010 have not been met. The Healthy People 2010 target for administration of the pneumococcal vaccine in adults ages 65 and older, for example, is 90%. As of 2008, research has shown, only 60% of that population was immunized.6

There are subgroups of immunocompromised people who will probably never achieve adequate antibody levels to ensure immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases (for example, measles and influenza can be deadly to the immunocompromised person, as they can be to the very young and the very old). This is an important reason why vaccination of the healthy population is essential: the concept of herd immunity.7 Herd immunity (or community immunity) suggests that if most people around you are immune to an infection and do not become ill, then there is no one who can infect you—even if you are not immune to the infection.

WHY SOME ADULTS MIGHT NEED VACCINES

Adults who were vaccinated as children may incorrectly assume that they are protected from disease for life. In the case of some diseases, this may be true. However:

• Some adults were never vaccinated as children

• Newer vaccines have been developed since many adults were children

• Immunity can begin to fade over time

• As we age, we become more susceptible to serious disease caused by common infections (eg, influenza, pneumococcus).8

Barriers to Vaccination

Barriers to vaccination are varied, but none is insurmountable. Some of these barriers include8-15:

Missed opportunities. Providers should address vaccination needs for both adults and children at each visit or encounter. According to the CDC, studies have shown that eliminating missed opportunities could increase vaccination coverage by as much as 20%.8,11

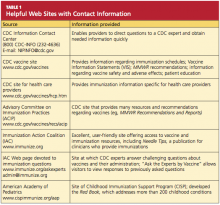

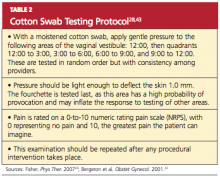

Provider misconceptions regarding vaccine contraindications, schedules, and simultaneous vaccine administration. These misconceptions may prompt providers to forego an opportunity to vaccinate. Up-to-date information about vaccinations and ongoing provider education are imperative to improve immunity among both adults and children against vaccine-preventable disease.8 Numerous Web sites and publications are instrumental and essential in furnishing the health care provider with the most current information about vaccinations (see Table 1, above, and Table 2,10,12-14).

A belief on patients’ part that they are fully vaccinated when they are not. It is important to provide a vaccination record and a return date at every vaccination encounter, even if just one vaccination has been administered on a given day. Participating in Immunization Information System,15 if one is available, is an efficient way to access computerized vaccine records easily at the point of contact.

Just as parents should be encouraged to bring their child’s vaccine record with them to every health care visit, adults are also called upon to maintain a record of all their vaccinations. Each entry in the immunization record should include:

• The type of vaccine and dose

• The site and route of administration

• The date that the vaccine was administered

• The date that the next dose is due

• The manufacturer and lot number

• The name, address, and title of the person who administered the vaccine.15

PRINCIPLES OF VACCINATION

There are two ways to acquire immunity: active and passive.

Active immunity is produced by the individual’s own immune system and usually represents a permanent immunity toward the antigen.10,16

Passive immunity is produced when the individual receives products of immunity made by another animal or a human and transferred to the host. Passive immunity can be accomplished by injection of these products or through the placenta in infants. This type of immunity is not permanent and wanes over time—usually within weeks or months.10,16

This article will concentrate on active immunity, acquired through the administration of vaccines.

CLASSIFICATION OF VACCINES

Vaccines are classified as either live, attenuated vaccine (viral or bacterial) or inactivated vaccine.

Live, attenuated vaccines are derived from “wild” or disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Through procedures conducted in the laboratory, these wild organisms are weakened or attenuated. The live, attenuated vaccine must grow and replicate in the vaccinated person in order to stimulate an immune response. However, because the organism has been weakened, it usually does not cause disease or illness.10,16