DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

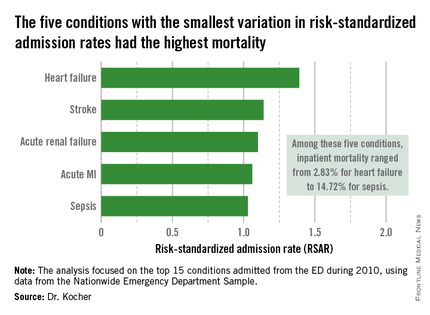

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

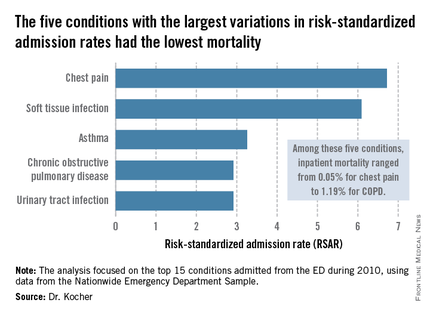

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.