Several million Americans, primarily those in their fifties and sixties, contracted hepatitis C virus (HCV) many years ago and are unaware of their infection and their risk for HCV-related liver disease. Screening at-risk patients is important because newer treatment regimens are curative and can reduce associated morbidity and mortality.

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver disease in the United States. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data indicates that 2.7 million people have chronic HCV infection; the CDC estimates 3.2 million.1-3 Yet these individuals may be asymptomatic for years, despite slow progression of sequelae (eg, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC]) that may silently unfold. Left untreated, chronic HCV infection is associated with a 15% to 30% risk for cirrhosis within 20 years, which subsequently confers an annual risk for HCC of 2% to 4%.4 Additionally, chronic HCV infection is now the leading indication for liver transplantation.3

Of note, 70% of those with chronic HCV infection were born between 1945 and 1965.2 This is believed to be attributable to viral transmission via contaminated blood, blood products, and organ transplants prior to the implementation of universal precautions for blood supply screening in 1992; and to past injection drug use, even if it occurred only once.3

In a recent analysis, it was determined that the clinical and economic burdens of chronic HCV infection increased in the past decade, and this trend is likely to continue during the next decade.5 For example, HCV was responsible for 15,106 US deaths in 2007, surpassing deaths caused by HIV for the first time.6 Since then, the number of HCV-related deaths has continued to increase, to 17,721 in 2011.7 Economic costs solely attributable to HCV infection are difficult to calculate, but estimates range from several hundred million dollars to $30 billion annually.5 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 185 million people worldwide are infected with HCV and that HCV is responsible for 350,000 deaths annually.4

The main goal of treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV RNA in serum 12 to 24 weeks after completion of treatment and thereby prevent or reduce the complications of HCV infection.3 Proactive screening, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of HCV infection can significantly reduce long-term morbidity and mortality.

INDICATIONS FOR HCV SCREENING

Recommendations for HCV screening have been developed by numerous organizations, including the WHO, CDC, US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (see Table 1).3,4,8,9-11 Screening should be offered to all individuals meeting one or more of the criteria. A 2012 CDC update calls for one-time testing for all persons born between 1945 and 1965 because of the disproportionately high prevalence of HCV infection in this cohort, which is five times greater than in the general population.11

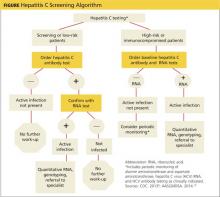

The initial screening tool for HCV infection is an HCV antibody test. A positive or reactive anti-HCV antibody result can signify either current or resolved infection, so a positive result should be followed with an HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) test to determine if active infection is present.4,8-10 See Figure on previous page for an HCV screening algorithm, which includes the points at which referrals to specialists are indicated.

A rapid HCV antibody test was approved by the FDA in 2011 and is favored because of its widespread availability, ease of use, rapid results, and low cost. Point-of-care testing is comparable in sensitivity and specificity to laboratory-based HCV assays and can utilize blood obtained via fingerstick or venipuncture.8 This form of testing facilitates HCV screening in a variety of settings, such as health fairs and emergency departments, as well as in high-risk settings such as methadone clinics.

Populations at increased risk for HCV infection are also at increased risk for hepatitis B virus (HBV), HIV, and tuberculosis infections; therefore, screening for these may also be warranted.4

PROGRESSION OF UNTREATED INFECTION

Just as with chronic HCV infection, patients newly infected with HCV are typically asymptomatic; the illness manifests with clinical symptoms in only 20% to 30% of cases.3 If symptoms do appear, they include fever, fatigue, dark urine, clay-colored stool, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, joint pain, and jaundice. These acute phase symptoms may last two to 12 weeks.12

Spontaneous clearance of the virus occurs in only 15% to 25% of cases (see further discussion under “Acute HCV.”).2,3 Even if a patient clears an HCV infection, if he or she falls within one of the at-risk categories (see Table 1), then periodic screening should continue because prior HCV infection does not protect against future infection.3

The progression of chronic HCV is indolent and often subclinical, with fatigue being the most common complaint. Other nonspecific symptoms may include nausea, anorexia, myalgia, arthralgia, weakness, and weight loss. One study noted that symptoms do not correlate with disease severity.13 In a 10-year prospective study, chronic HCV infection increased mortality when the infection was acquired at an early age (younger than 50) and/or when cirrhosis developed.14 Patients with cirrhosis progress to liver decompensation at a rate of 3% to 6% annually.15

In addition to liver disease, HCV infection is associated with an increased risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.3 HCV may also induce insulin resistance, which increases the risk for hepatic fibrosis. Other studies document HCV-induced cognitive impairment, but little scientific data is yet available as to its pathogenesis.16

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic testing for suspected HCV infection begins with an antibody test.8 A positive antibody test indicates one of three possibilities: active infection, resolved infection, or a false-positive result. Two drawbacks of HCV antibody testing are that immunocompromised patients may falsely test negative and that antibodies cannot be detected until eight to 12 weeks after the infection is acquired.11 A positive antibody test should be confirmed with an HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) RNA test.8,10

HCV RNA testing can detect the virus earlier than antibody testing—as early as two weeks after infection. Although a positive HCV RNA test confirms current HCV infection, its higher cost precludes its use as an initial diagnostic test for lower-risk patients.

In patients who test negative but for whom there is a high index of suspicion for HCV infection (eg, jaundiced patient with an elevated alanine aminotransferase level [ALT]), or for a health care worker with a recent bloodborne HCV exposure, testing for HCV antibodies, HCV RNA, and ALT levels should be ordered at regular intervals for a period of six months.10

Acute versus chronic infection

Distinguishing acute and chronic HCV is difficult. A determination that HCV is newly acquired requires a documented negative baseline antibody test, followed by laboratory evidence of seroconversion. This is typically only seen in cases where there has been a recent, known exposure to the virus.

Both HCV antibody and RNA testing are recommended when screening high-risk patients, including those who are immunocompromised, on hemodialysis, or have had a recent exposure to HCV-positive blood.10 Rapid PCR HCV RNA tests can assess both viral load and genotype (see discussion of HCV genotypes under “Chronic HCV”).17 This information helps guide and measure patient response to treatment.

Liver disease severity

Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are serious complications of HCV; hepatomegaly or splenomegaly may or may not be present on physical examination and patients may require liver biopsies to evaluate disease stage.18 An assessment of the severity of liver damage can determine the urgency of treatment and predict treatment efficacy.

Biopsy results permit the grading of inflammation and nodularity and the staging of septal fibrosis, which can reliably predict future progression of the patient’s disease.19 However, liver biopsy is invasive, painful, and may contain sampling errors; complications may include bleeding, infection, and occasionally accidental injury to a nearby organ. An initial noninvasive assessment may be performed using vibration-controlled transient liver elastography, an ultrasound-based technology that measures liver stiffness, which correlates well with the degree of fibrosis or cirrhosis. Elastography, along with measurement of direct serum biomarkers that are produced by activated hepatic stellate cells involved in fibrosis, affords an accurate, noninvasive means of assessing liver damage.10

Continue for treatment options >>