STEPS YOU CAN TAKE DURING THE OFFICE VISIT

Although it is not feasible for most FPPs to provide comprehensive treatment for PD, key elements from specialized therapies can be integrated into your management of these patients. Steps you can take include using validation, promoting mentalization, and managing countertransference.

Validation, which is a component of DBT, is providing the expressed acknowledgement that the patient is entitled to her feelings. This is not the same as agreeing with a position the patient has taken on an issue, but rather conveying the sense that one sees how the patient might feel the way she does. A study of women with borderline PD and substance abuse found a validation intervention by itself was significantly helpful.34 Validation can contribute to a “corrective emotional experience.” For instance, your supportive acknowledgement of a patient with a history of abuse or neglect may counter the patient’s expectation of being invalidated, and over time this can reduce the patient’s defensive rigidity.

Mentalization. Psychodynamic treatment involves a similar tack; clinicians empathize with the patient’s emotional state while also demonstrating a degree of separateness from the emotion.23-25 This promotes mentalization in the patient—the ability to contemplate one’s own and others’ subjective mental states.18 Mentalization is often impaired in PD patients, who presume to “know” what others are thinking. A patient, for instance, “just knows” that her friend secretly hates her, based on a vaguely worded text message.

You can help patients with mentalization by taking an inquisitive “not knowing” stance and by emphasizing a collaborative and reflective approach toward a given problem—to examine the issue together, from all sides. You can point out that while a patient is entitled to feel whatever he is feeling, it may not be in his best interest to act on the feelings without adequately considering the potential consequences of the action. This helps the patient to distinguish thoughts, feelings, and impulses from behavior. It also teaches the value of anticipatory thinking, impulse control, and affect regulation.

Countertransference. Managing your emotional reactions to a patient with PD is a well-documented challenge.35 Your feelings about the patient, known as countertransference, can range from considerable concern and sympathy to severe frustration, bewilderment, and frank hostility. A common reaction is the sense that one must “do something” to respond to the patient’s emotional distress or interpersonal pressure. This may trigger an impulse to give advice or offer tests or medications despite knowing that these are unlikely to be helpful. A more useful response may be to tolerate such feelings and listen empathically to the patient’s frustration. Recognizing subtle countertransference can guard against extreme reactions and maintain an appropriate clinical focus. Discussion with a trusted colleague can be helpful.

Psychodynamic approaches consider managing countertransference to be a therapeutic intervention, even when psychotherapy is not explicitly being carried out. Strong emotional responses may reflect something that the patient needs the clinician to experience, as the patient cannot bear to experience it himself. The patient needs to see—and learn from—the clinician’s handling of unbearable (for the patient) feelings. This occurs at a level of unconscious communication and may be repeated over time. Although not discussed with the patient, a clinician’s capacity for self-containment and provision of undisrupted, good medical care is in itself a psychotherapeutic accomplishment.

Based on Bob’s history of interpersonal conflicts and perceived persecution by coworkers, the FPP consults with a psychotherapist colleague, who says Bob’s chronic mistrust and social isolation suggest he may have a severe identity disturbance and unspecified PD with paranoid and schizoid features. Because Bob refuses to see a therapist, his FPP decides to focus on promoting small improvements in Bob’s interpersonal interactions and reducing absenteeism at work.

The FPP validates Bob’s feelings (“it can be very stressful to constantly feel like others are at odds with you”) and tries to promote mentalizing (“I want to understand more about what you think regarding your work situation and your coworkers. Let’s try to look at this from all perspectives—maybe we can come up with some new ideas.”)

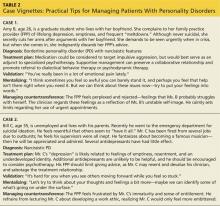

Despite wanting to help his patient, the FPP feels uneasy and reluctant to engage with Bob, who likely evokes such feelings to keep others at a distance. The FPP tactfully seeks to remain Bob’s ally without endorsing his distorted interpretation of events. Given Bob’s paranoid rejection of therapy, the FPP refrains from making further such recommendations. The FPP’s interventions, however, may help Bob warm to the idea of further help over time, and the FPP’s supportive stance will help to ameliorate the patient’s distress. (Additional examples of how to use the strategies described in this article can be found in Table 2.)

References on following page >>