Overview

Palliative medicine in the ED represents a paradigm shift for the emergency physician (EP)—from identifying and stabilizing acute medical and surgical conditions to providing symptomatic comfort care to a dying patient. When the ED became the “safety net” for patients who have serious, life-limiting illnesses,1-3 it also became the most frequent place where such care is initially sought4—although not considered an ideal place to begin such care.

In one study, approximately 40% of dying patients presented to the ED during their final 2 weeks of life.5 With the ED becoming more recognized as a location for palliative care, the EP plays a key role in the care of these patients. The 2013 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine explicitly lists palliative medicine within the EP’s scope of practice.6 Further support for providing palliative care in emergency medicine includes the cosponsorship of Hospice and Palliative Medicine subspecialty board certification by the American Board of Emergency Medicine in 2008. Finally, palliative care medicine principles have been endorsed in the “Choosing Wisely” initiative of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Essential Palliative Care Skills

Quest et al7 have identified the following 12 primary palliative care skills in which every EP should be competent:

- Assessment of illness trajectory;

- Determination of prognosis;

- Communication of bad news;

- Interpretation and formation of an advance care plan;

- Allowance of family presence during resuscitation;

- Symptom management (both pain and nonpain);

- Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments;

- Management of imminently dying patients;

- Identification and implementation of hospice and palliative care plans;

- Understanding of ethical and legal issues pertinent to end-of-life care;

- Display of spiritual and cultural competency; and

- Management of the dying child.

Although all of the above are important skills, this paper focuses on the symptom management of pain and nonpain (skill 6) in patients presenting to the ED with a life-limiting illness. The evidence base for these treatments is limited due to the many methodological challenges faced when studying symptoms in patients who are at end of life.

Pharmacologic Management of Symptoms

Recent research has found that symptom burden is high at end of life. Despite the increase in attention to these patients and their needs, symptoms including pain, depression, and delirium have repeatedly increased between 1998 and 2010.8 A 2013 study recommended that a minimum of four classes of medications be considered for patients who are at end of life: opioid (for pain); benzodiazepine (for anxiety); antipsychotic (for delirium and nausea); and antimuscarinic (for excessive secretions).9 The role and indications for each of these drug classes will be discussed.

Palliative Care Intervention

Though EPs frequently request specialty and subspecialty consultation for ED patients, they usually do not consider a palliative care medicine consult for the dying patient. Palliative care medicine utilizes an interdisciplinary, collaborative, team-based approach to decrease the pain and suffering of patients with advanced illness.10

Benefits from early palliative care intervention in the ED include improved symptom management, improved patient and family satisfaction, improved outcomes, decreased length of stay, less use of intensive care units, and less costs.4

Pain Management

Pain is one of the most devastating symptoms that a patient can experience, and its management is an integral component of palliative care medicine. Initial evaluation must include appropriate assessment of the pain and its impact on a patient’s function and quality of life.

The general approach to pain management follows the World Health Organization pain ladder. For mild to moderate pain, step 1 begins with acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), with or without an adjuvant such as an antidepressant or anticonvulsant. If pain persists, step 2 involves the addition of an opioid. For moderate to severe pain, step 3 involves the addition of stronger opioids, such as hydromorphone, morphine, and oxycodone. Typically, a patient with a serious, life-limiting illness who presents to the ED for help will likely require treatment with strong opioids (step 3).

Opioids

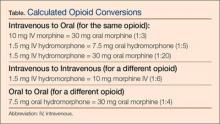

In patients requiring step 3 management, opioids are the primary medication used to manage pain. An initial equivalent dose of morphine 5 mg intravenously (IV) is appropriate in an opioid-naïve patient. The adage of “starting low and going slow” is important to follow; however, an important corollary is “…and use enough.” If a patient’s pain is not controlled with initial dosages, additional bolus doses of 50% to 100% increments will be necessary. Because opioids do not have a ceiling effect, it is important to understand that dosages may seem very high for some patients compared to others. In this population, ensuring baseline pain control, with either an oral long-acting formulation or a continuous IV infusion, is important.11