Case

A 25-year-old college student presented to the ED following a near-syncopal episode. The patient stated he had felt lightheaded and had fallen to his knees immediately after taking a shower earlier that morning, but did not experience any loss of consciousness or injury. He denied a history of syncope or any recent trauma or fatigue. A review of the patient’s systems was negative. His medical history was remarkable for irritable bowel syndrome; he had no surgical history. Regarding his social history, he admitted to occasional alcohol use but denied any tobacco or illicit drug use. He was not on any current prescription or over-the-counter medications and denied any allergies.

The patient’s initial vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 112/58 mm Hg; heart rate, 86 beats/min; temperature, 97.9°F; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The patient reported pain in his left shoulder, epigastric region, and right flank. He rated his pain as a “4” on a 0-to-10 pain scale.

On physical examination, the patient was alert and oriented; he was thin and had mild pallor. His head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat; cardiac; pulmonary; and neurological examinations were normal. The abdominal examination revealed a soft, minimally tender epigastrium but with normal bowel sounds. Initial laboratory studies were remarkable for low hemoglobin (Hgb; 12.0 g/dL) and elevated aspartate transaminase (105 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (168 U/L), total bilirubin (1.6 mg/dL), and glucose (179 mg/dL) levels. The patient’s troponin I and lipase levels were within normal range. An electrocardiogram was unremarkable.

Given the patient’s elevated hepatic enzymes, right upper quadrant ultrasound was obtained, which demonstrated a normal gallbladder, a moderate amount of complicated free fluid (with hyper-echoic densities suggestive of coagulated blood) in all four quadrants, and splenomegaly measuring 13.7 cm (Figure 1a and 1b).

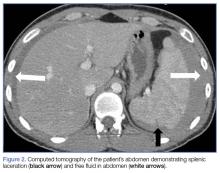

Based on the ultrasound findings, an abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was immediately obtained, which revealed free fluid, a sentinel clot sign around the enlarged spleen measuring 15 cm, and a posterior splenic laceration measuring 1 cm (Figure 2).The patient’s status, including his vital signs, remained stable throughout his entire ED course. However, repeat laboratory studies taken 4 hours after initial evaluation revealed a further decrease of Hgb to 8.6 g/dL, for which the patient was given IV fluids and 2 U of packed red blood cells.

He was admitted to the intensive care unit, where he continued to be managed nonoperatively. Over the next 2 days the patient remained stable and his Hgb trended up. Additional laboratory testing prior to discharge revealed the following results:Positive:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)

- Viral capsid antigen (VCA) immunoglobulin G

- VCA immunoglobulin M

Negative:

- Mononuclear spot test

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Hepatitis B and C

- Antinuclear antibodies

- Venereal disease research laboratory test

The rest of the patient’s recovery was uneventful, and he was discharged home in stable condition on hospital day 3.

Discussion

Although the spleen is the most common intra-abdominal organ that can rupture with blunt abdominal trauma, splenic rupture in the absence of trauma is very rare. Nontraumatic splenic rupture (NSR) has been associated with pathological and nonpathological spleens.1,2 A systemic review of NSRs showed that 7% of the 845 patients in the review had completely normal spleens; the remaining 93% had some form of splenic pathology.1

Etiology

The top three causes of splenic enlargement associated with NSR include hematologic malignancies, viral infections, and inflammation.1,2 Although viruses, such as EBV and cytomegalovirus, represent almost 15% of the pathological causes of NSR, it is not uncommon for a patient to have multiple pathological processes present.1 Our patient’s enlarged spleen was due to acute infectious mononucleosis.

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnosing NSR can be challenging and it is often missed or discovered incidentally during evaluation (as was initially the case with our patient).3 Several signs and symptoms present in our patient were red herrings that warranted closer analysis. The patient’s complaint of left shoulder pain suggested left hemidiaphragm irritation from the NSR. Furthermore, our patient’s near-syncopal episode was possibly due to acute vagal simulation from the initial contact of blood with the peritoneal cavity.4 The maximal vagal stimulus was likely transient, as our patient returned to baseline after a brief near-syncopal episode.