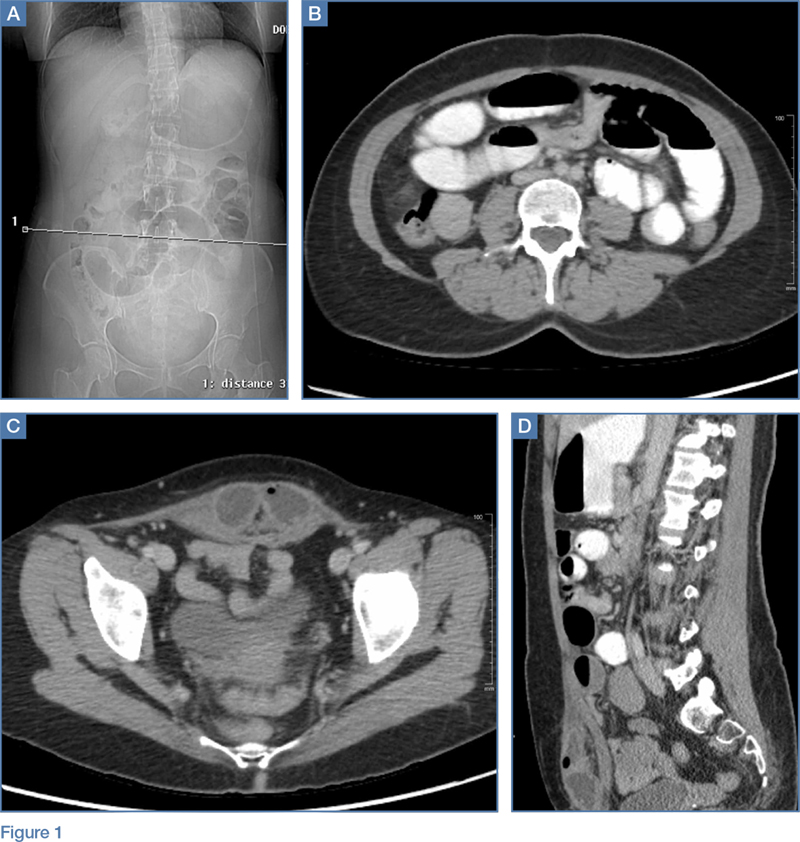

A 45-year-old woman with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome presented to the ED for evaluation of acute abdominal pain. The patient’s surgical history was significant for a cesarean delivery 6 months prior to presentation. Abdominal examination revealed a well-healed suprapubic cesarean incision scar, which was tender upon palpation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast were ordered; representative images are shown above (Figure 1a-1d).

What is the diagnosis? What are the associated complications and preferred management for this entity?

Answer

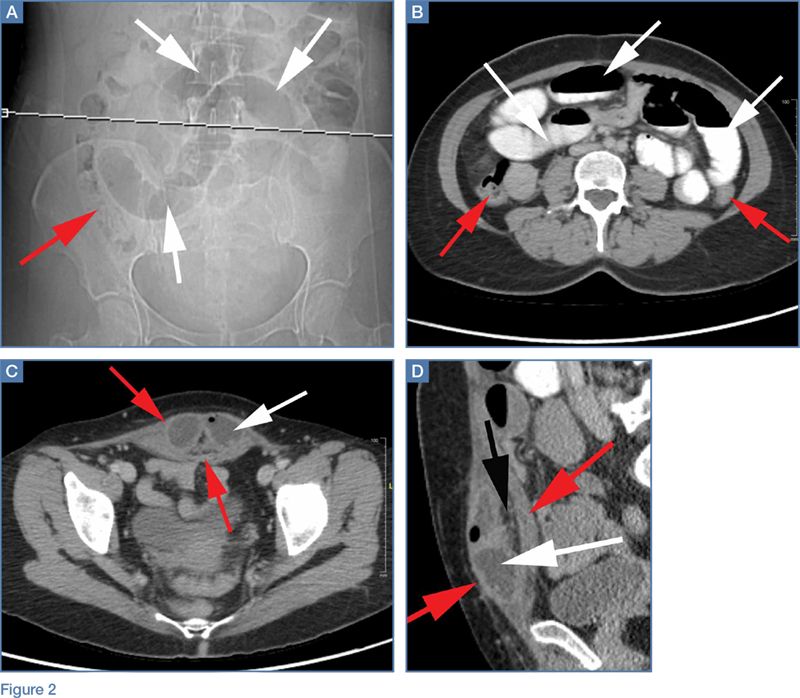

The scout image from the CT scan shows multiple dilated loops of small bowel (white arrows, Figure 2a) and only a small amount of air within a decompressed colon (red arrow, Figure 2a). The multiplanar CT image confirmed multiple dilated small bowel loops (white arrows, Figure 2b) and the decompressed large bowel (red arrows, Figure 2b), indicating the presence of a small bowel obstruction. A distal small bowel loop (white arrows, Figure 2c and 2d) was identified in a hernia sac within the walls of the rectus abdominis muscle (red arrows, Figure 2c and 2d). Mesenteric stranding within the hernia sac was suggestive of incarceration (black arrow, Figure 2d). No signs of intestinal ischemia, such as pneumatosis or wall thickening, were present.

An exploratory laparotomy was emergently performed, which confirmed the presence of incarcerated small bowel within the posterior rectus sheath defect without evidence of strangulation. Reduction of small bowel and primary closure of the hernia defect was subsequently performed without complication.

Abdominal Wall Hernias

Abdominal wall hernias are common in the United States, with more than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs performed annually.1 A posterior rectus sheath hernia is a rare type of abdominal wall hernia; the majority are postsurgical (as seen in this patient) or posttraumatic, with only a few reported congenital cases.2

Anatomy

The rectus sheath encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and is composed of the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. The aponeuroses form an anterior and posterior sheath, which together serve as a strong barrier against the herniation of abdominal contents, accounting for the rarity of a spontaneous rectus sheath hernia. However, inferior to the umbilicus (below the arcuate line), the posterior rectus sheath is composed primarily of transversalis fascia, which may make this region more susceptible to herniation.3 Additional predisposing factors to herniation include increased muscle weakness and elevated intra-abdominal pressure, such as that which occurs during pregnancy or from ascites.4

Clinical Presentation

Like other abdominal wall hernias, the clinical presentation of posterior rectus sheath hernias is nonspecific. Patients may be asymptomatic or may develop abdominal pain, distension, and vomiting as a result of acute complications that necessitate emergent surgery. During history-taking, inquiry into a patient’s surgical history is crucial because it may raise clinical suspicion for an abdominal wall hernia, as was the case in our patient, who recently had a cesarean delivery.

Diagnosis

Because prompt and accurate diagnosis of acute complications of abdominal wall hernias is essential, imaging studies are typically required for diagnosis. Computed tomography is the modality of choice based on its ability to provide superior anatomic detail of the abdominal wall, permitting identification of hernias and differentiating them from other abdominal masses, such as hematomas, abscesses, or tumors. Additionally, CT is able to detect early signs of hernia sac complications, including bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation.5

Treatment

Treatment for a posterior rectus sheath hernia is surgical with primary closure being the preferred method. Prosthetic repair may also be performed, particularly when the hernia defect is large, but it has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intestinal strangulation.3