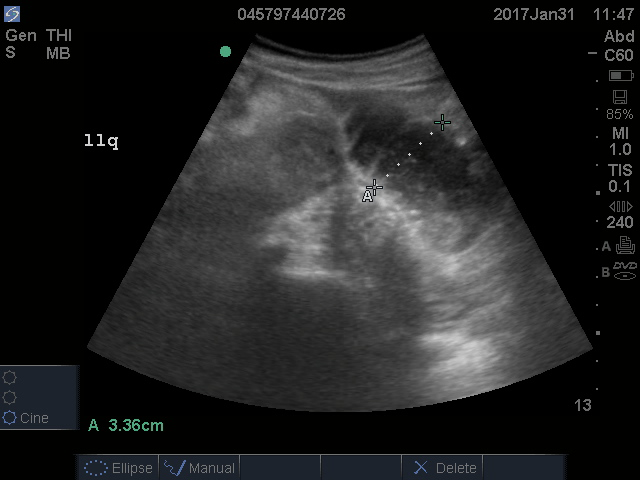

A fluid-filled small intestinal segment >2.5 cm is consistent with a diagnosis of SBO. Measuring the diameter of the small bowel is both the most sensitive and specific sign; a measurement of greater than 2.5 cm is diagnostic, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 91% (see Figure 4).6 This can be somewhat difficult to visualize, as bowel loops are multidirectional and diameters can mistakenly be taken on an indirect cut; to avoid over- or underestimation of bowel diameter, you may want to measure in the short axis using a transverse cross-sectional view of the bowel.

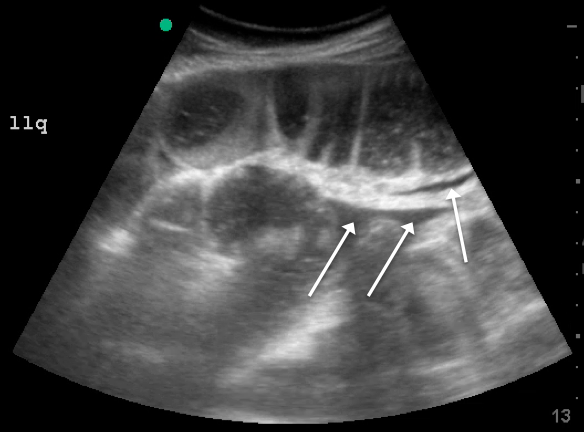

Lack of peristalsis is suggestive of a closed-loop obstruction. However, this finding may be more difficult to visualize, as it requires several continuous minutes of scanning or repeated exams to truly establish absent peristalsis. In prolonged courses of SBO, the bowel wall can measure >3 mm, which suggests necrosis, warranting accelerated surgical intervention. In addition, the detection of extraluminal peritoneal fluid can help determine the severity of the SBO, and small versus large fluid amounts can help determine whether medical or surgical management is warranted (see Figure 5).7

DISCUSSION

Increased time to diagnosis of SBO can lead to prolonged patient suffering and greater complication rates. The gold standard for diagnosing SBO—CT with intravenous and oral contrast—can take hours, requiring patients, who are often nauseated, to ingest and tolerate oral contrast. In the past, an “obstructive series” of x-rays would have been used early in the work-up of possible SBO.6

Recent literature suggests that POCUS is not only faster, more cost effective, and advantageous (involving no ionizing radiation), but also more accurate than x-rays. Specifically, a meta-analysis by Taylor et al showed pooled estimates for obstructive series x-rays have a sensitivity (Sn) of 75%, a specificity (Sp) of 66%, a positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of 1.6, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.43.1 On the other hand, pooled results from ED studies of emergency medicine (EM) residents performing POCUS in patients with signs and symptoms suspicious for SBO showed POCUS had a Sn of 97%, Sp of 90%, +LR of 9.5, and a -LR of 0.04.1,5,8 While detractors point to the operator-dependent nature of POCUS, literature suggests that with EM residents novice to POCUS for SBO (defined as less than 5 previous scans for SBO) were given a 10-minute didactic session and yielded Sn 94%, Sp 81%, +LR 5.0, -LR 0.07.5 Unluer et al trained novice EM residents for 6 hours and found them to yield Sn 98%, Sp 95%, +LR 19.5, and -LR 0.02.8 Thus, while it is no surprise that those with more training attain better results, both studies show it does not take much time for EM providers to surpass the accuracy of x-rays with POCUS.

CASE CONCLUSION

The findings on POCUS highly suggested the diagnosis of an SBO. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was ordered to further evaluate obstruction, transition point, and possible complications, including signs of ischemia per surgical request. CT demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel with transition point in the right lower quadrant, with a small amount of mesenteric fluid consistent with SBO with possible early bowel compromise due to ischemia. General surgery admitted the patient; conservative treatment with serial abdominal exams, nasogastric tube, NPO and bowel rest was ordered. The patient’s diet was gradually advanced, and she was discharged on the eleventh day of hospitalization.

SUMMARY

POCUS is a useful non-invasive tool that can accurately diagnose SBO. POCUS has increased sensitivity and specificity when compared to abdominal X-rays. This bedside imaging will not only give the ED provider rapid diagnostic information but also lead to expedited surgical intervention.