A tragic discovery

After an all-day deposition, Dr. Matthew Seaman returned home worn out. He had purchased three bottles of wine, although he was never a drinker, his wife recalled.

“My husband came home from the deposition, not relieved as expected, as he had been dreading the event, but demoralized, more depressed, and all sense of human worth had been beaten out of him,” Dr. Linda Seaman said. “He did not wish to celebrate. He wanted to die and said so.”

The following day, Dr. Linda Seaman left messages with her husband’s psychiatrist with concerns about his declining mental state. A receptionist repeatedly advised that the psychiatrist does not communicate with patients or families by phone and that the messages would be relayed, Dr. Linda Seaman said. After getting nowhere during the second call, she handed her husband the phone.

“Matt told the receptionist he was suicidal and wished to speak with [the psychiatrist] as his medications were not helping him,” she said. “[She] told my husband to go to the ER. My husband is an ER doctor, has served in this community for 30 years, and he told [her]: ‘I am not going to the ER! And I am not going to be hospitalized at Memorial hospital ever again. It was a waste of time.’ ”

None of the calls were returned.

That night, Dr. Matt Seaman went to the couple’s basement to sleep as he often did because of his insomnia. Dr. Linda Seaman was giving a presentation at the medical school the next day and her husband knew she needed her sleep.

The next day, after finishing her slides, Dr. Linda Seaman went downstairs to check on her husband and say goodbye. She entered the room and found he had hanged himself.

The key to prevention

A vital step to preventing physician suicide is recognizing the mental harm that lawsuits and other professional scrutiny can cause, Dr. Andrew said.

“The key is individual awareness that suicide can be an outcome of litigation and that some of the earliest warning signs are going to be subtle, such as withdrawal, isolation, sadness, and some degree of immobility,” Dr. Andrew said. “We, as sentient fellow physicians, need to reach out to each other, in any situation, not just litigation, but it also applies to licenser actions and even bad patient outcomes. It’s up to us to be alert and support colleagues who are under any kind of emotional distress.”

To that end, more institutions and employers should develop peer-to-peer and group support services for doctors going through stressful experiences, said Dr. Andrew, founder of MD Mentor, which provides litigation support and consulting services to physicians. (An audio interview with Dr. Andrew on litigation stress experienced by physicians is available at the end of this article.)

At the same time, it is important for medical communities to identify more psychiatrists who are comfortable caring for their colleagues and open to seeing them quickly, Dr. Myers said.

“The bottom line is this: In medical communities in which mental health professionals step up to the plate and make it easier for symptomatic colleagues to consult them in their hour of need, there is less suffering and earlier initiation of treatment, treatment that can be life-saving and suicide preventing,” he said.

Taking physician wellness seriously is vital, said Dr. Yellowlees, who is one of about 30 chief wellness officers across the country. In this role, Dr. Yellowlees aims to improve access to care for all physicians, whether for treatment of depression/suicidality, burnout prevention, or support after traumatic events. He also teaches a 6-month fellowship course on clinical health and well-being, which begins its second cohort in April 2020.

Dr. Zisook said one promising change already underway is that more people are discussing physician suicide and sharing the real stories behind the statistics.

“That’s an important first step, and it’s finally happening,” he said. “We can do ourselves and our colleagues a whole lot of good by facing, acknowledging, and talking about the issues and breaking through this cloud of silence that we all have about physician health.”

A strong life and legacy

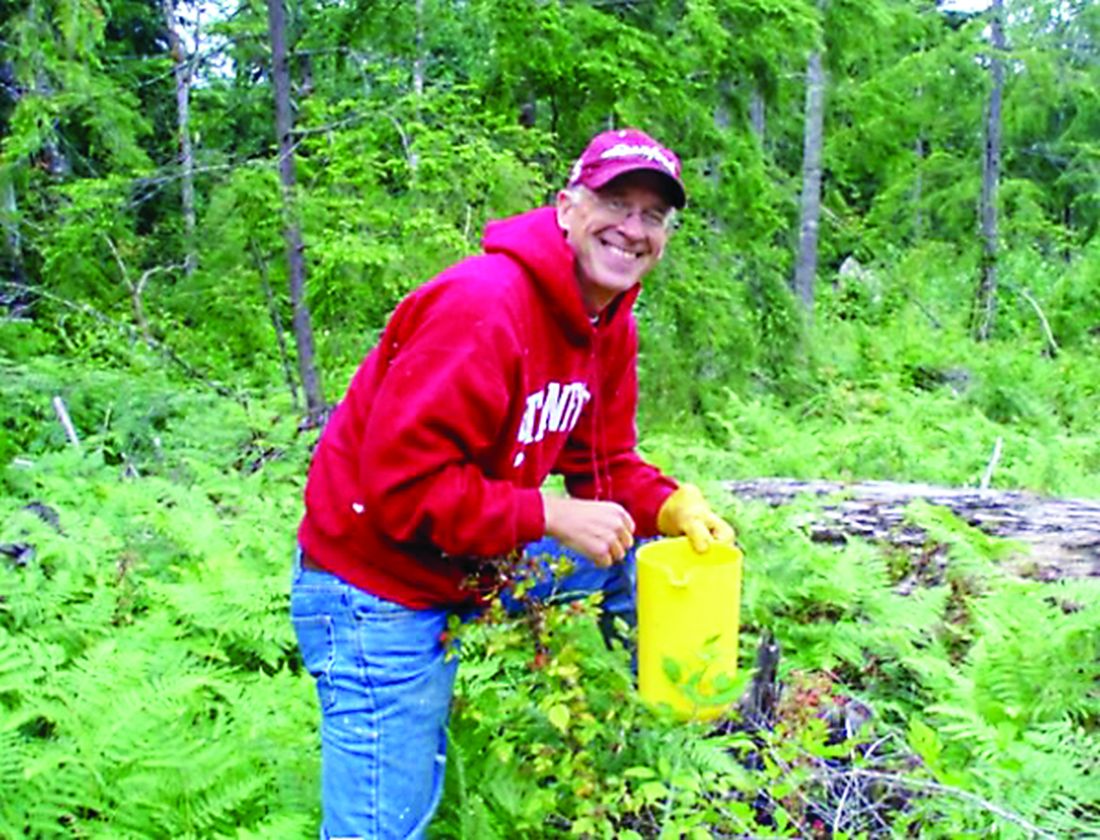

For the first time in many seasons, the Douglas firs that line Dr. Matt Seaman’s tree farm near the Nisqually River are without the meticulous hand of their doting tree farmer. The absence is one of many deep holes left by the doctor’s death.

“Reality is taking its toll in little snippets,” Dr. Linda Seaman said. “I don’t have anyone to travel with. I miss my best friend.”

But the roots of Dr. Matt Seaman’s life and legacy remain strong.

He would want to be remembered as a provider for his family, an emergency medicine expert, an environmentalist, an entrepreneur, and a lover of German Shepherds, his wife said. She believes his life embodied one of the lines he often repeated: “Embrace the journey.”

After her husband’s death, Dr. Linda Seaman secured her own legal counsel, who was able to settle the lawsuit against her husband, she said, noting that she paid the legal costs and settlement.

Since the ordeal, Dr. Linda Seaman has become an advocate for change in medical board processes, better care for physicians, and more awareness during the litigation process.

“If I can spare one physician and their family from going through the suffering our family endured, and help those ‘investigated’ be more supported and educated on how these current regulatory and legal systems work, it will be worth it,” she said. “ ... A more humane, transparent, compassionate process that protects physicians and give them fair peer review and ongoing support during these difficult journeys would save physician lives.”

Click below to listen to an interview with Dr. Andrew on litigation stress experienced by physicians.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is staffed around the clock at 1-800-273-8255; www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org provides information, resources, and local crisis centers.

*This article was updated 1/19/2020.