However, when the injury such as an open fracture or severe displacement is obvious, immediate stabilization is critical so as not to permit any additional harm. An arm board is typically used to accomplish this. In addition, pain control should never be overlooked, either with intravenous opioids or more appropriate oral or intranasal analgesia.4,5 In cases of significant trauma, always remember ABC assessment (airway, breathing/oxygenation, and circulation), despite the eagerness to give attention to what may be an obvious fracture.

Workup

Although the use of ultrasound and other modalities is becoming more popular in some settings, it is still commonplace to begin the evaluation of a potential fracture or dislocation with plain film X-rays. Before sending a patient to radiology, always stabilize any unstable fracture to avoid further injury or potentiate neurovascular compromise. In most cases, three views, including anteroposterior, true lateral, and oblique, are obtained. If a fracture is unclear, it may be helpful to image the opposite extremity for comparison. The location of a fracture and its characteristics greatly influence acute-care management, as well as patient disposition, the need for consultation with orthopedics, and follow-up expectations and instructions.

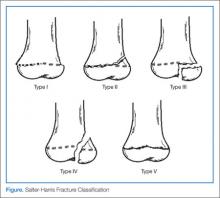

Salter-Harris Fracture Classification

The physes of bones in growing children are particularly vulnerable sites of fracture since they have not yet fused. The five generally accepted types of fracture according to risk of growth disturbance are illustrated in the above Figure and are differentiated as follows:

Type I. This type of fracture is exclusive involvement of the physis itself, separating the metaphysis from the epiphysis. Since plain films may not reveal any visible fracture, the clinician should have a high index of suspicion if the physical examination elicits point tenderness over the growth plate. When in doubt if a fracture is present, always splint. Type I fractures of the physis tend to heal well, without significant consequence.

Type II. As with type I fractures, type II involve the physis, but also have a fragment of displaced metaphysis—the most common of all physeal fractures. Without significant displacement, these fractures also tend to have good outcomes.

Type III. Rather than involving the physis and metaphysis, type III fractures involve the epiphysis and therefore the joint itself. It is because of the epiphyseal displacement that these fractures tend to have a worse prognosis with joint disability and growth arrest. Thus, establishing alignment is imperative. The distal tibial Tillaux fracture is an example and requires internal fixation for optimal healing.

Type IV. Similar to a type III fracture, with the fracture extending proximally through a segment of the metaphysis, type IV fractures are treated similar to type III fractures. Due to joint involvement, an orthopedic consultation is warranted.

Type V. This type represents compression fractures of the physis. As the visibility of these fractures is poor on plain films, diagnosis can be challenging. However, history of axial compression injury may help lead the clinician to an accurate diagnosis. Since there is a high incidence of growth disturbance in type V fractures, compression affecting other areas such as the spine should also be considered.

Certainly not all pediatric fractures will involve a physis. A detailed description and management of other unique types of pediatric fractures is discussed in other articles in this feature.

Splinting Basics

Once the decision is made to apply a splint to a fracture, certain basic precautions should first be taken. Initially, any significant lacerations or abrasions should be thoroughly irrigated, cleansed, and dressed appropriately. Next, the physician should reevaluate and document both neurological status and perfusion of the area, particularly distal to the fracture site.

One commonly overlooked step in management of any fracture is pain control. It is advisable to consider administering medication prior to splinting on a case-by-case basis and for all fractures requiring reduction.

Materials and Methods

Prepackaged fiberglass splints have become a popular, efficient, and less-messy material of choice in pediatric splinting. Alternatively, plaster of Paris—although a bit more cumbersome—has some advantages, including low cost and a tendency to mold more easily to the extremity being splinted.7 When using plaster, strips should be cut a little longer than the anticipated length needed since they may shrink during curing. The unaffected limb should be used to gauge the measurement needed.

Regardless of the material chosen, all splinting should begin with the application of a stockinette tube dressing over the skin, leaving a distal opening over fingers or toes. This should be followed by a padding material (eg, Webril), beginning distally and rolling proximally, being sure to have approximately 50% overlap of each roll. Extra padding should be rolled over any bony prominence (eg, ulnar stylus) to avoid discomfort or pressure sores once the splint is applied.2