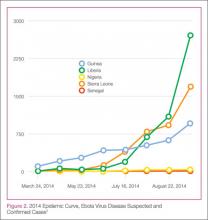

In this age of globalization, just a few hours of air travel separates even the most remote places in our world. Given this reality, the recent epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa (Figure 1) has arrived on the doorstep of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Ill and potentially infected US healthcare workers and missionaries brought home for treatment and quarantine, plus the travel of the general population through the affected countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, require all acute-care providers to be cognizant that this deadly disease may present in any community ED in the United States. Awareness and knowledge of the appropriate steps to manage care safely and effectively, while mindfully preventing the potential for viral transmission, is paramount.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers are manifestations of four distinct families of RNA viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, flaviviruses, and filoviruses. All of these families of viruses depend on a natural insect or animal (nonhuman) host and are thus restricted geographically to the regions where the endemic hosts reside. The viruses can only infect a human when one comes into direct contact with an infected host; this human becomes an infectious host when symptoms of disease develop and subsequently, the possibility of transmission to other close direct human contacts exists.

Ebola Virus Species

The family within which the Ebola virus species are classified is the filoviruses. Five species of Ebola filovirus have been isolated to date: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus), Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus), and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans. This epidemic has been attributed to a variant of the Zaire species.2 Transmission through direct contact with body fluids of febrile live infected patients and the postmortem period continues in communities and healthcare sites, as lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and meticulous environmental hygiene remains a challenge in many of these settings.

Clinical Presentation

In EVD, the onset of symptoms typically occurs abruptly at an average of 8 to 10 days postexposure and includes fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise; in some patients, an erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, neck, trunk, and arms erupts by days 5 to 7.1 The nonspecific nature of these early signs and symptoms warrants caution in any patient known to have traveled in an endemic country with potential exposure to body fluids of infected patients—underscoring the importance of both obtaining a complete travel history to determine the potential for disease exposure in patients presenting with infectious-disease symptoms and effectively communicating this information to all ED staff.

In addition, such caution includes healthcare mission workers caring for Ebola patients, those involved in butchering infected animals for meat, and persons participating in traditional funeral rituals for those deceased from Ebola without the use of adequate PPE and/or environmental hygiene. Other more common infectious diseases with shared features of EVD must also be considered at this stage and include malaria, meningococcemia, measles, and typhoid fever, among others.

After the first 5 days of exposure, progression of symptoms may include severe watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and/or confusion. Conjunctival injection may also develop. Not all patients will have signs of hemorrhagic fever with bleeding from the mouth, eyes, ears, in stool, or from internal organs, but petechiae, ecchymosis, and oozing from venipuncture sites may develop. Those at the highest risk of death show signs of sepsis, such as shock and multiorgan system failure, which may include hemorrhagic manifestations, early in the course of their illness. Patients with these complications typically expire between days 6 to16.1 Survivors of the disease tend to have fever with less severe symptoms for a period of several more days, and then begin to improve clinically between days 6 to 11 after onset of symptoms1 (Figure 3).

Ecology

A zoonotic filovirus transmissible from animal populations to humans causes EVD. Research strongly suggests that fruit bats are the reservoir and hosts for this filovirus. Direct human contact with bats or with wild animals that have been infected by bats initiates the human-to-human transmission of EVD.3