Case

A 20-year-old woman with a history of asthma and cigarette smoking presented to the ED twice within the same week. At the initial presentation, the patient stated that she had been experiencing symptoms of an upper respiratory infection over the past 4 days which had progressed to difficulty breathing. She further noted that these symptoms were also consistent with childhood asthma exacerbations. In addition to childhood asthma, the patient’s medical history included chronic dermatitis, for which she had been taking oral doxycycline daily.

The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) corticosteroids and an albuterol/atrovent nebulizer. Based on significant response to treatment and improvement, she was discharged on a 5-day steroid burst and albuterol meter-dose inhaler. She was also counseled to continue taking doxycycline daily for the chronic dermatitis.

Two days after discharge, the patient returned to the ED with episodes of coughing followed by worsening shortness of breath and sharp chest pain that radiated into her neck and back, which she described as unbearable. Neither the pain nor shortness of breath responded to albuterol.

The patient’s vital signs at this second presentation were: blood pressure, 144/88 mm Hg; heart rate, 98 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 28 breaths/minute; and temperature, 97.8˚ F. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 94% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was uncomfortable and in mild distress. She was visibly tachypneic with diminished breath sounds, but no wheezing, rales, or rhonchi were appreciated on auscultation. Cardiac auscultation was likewise normal. The patient had a visceral sense of pain on palpation of her anterior chest wall, but no crepitus was appreciated. Both an electrocardiogram and chest X-ray (CXR) were normal, but laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 18.4 u/L (4.0-11.0).

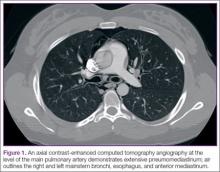

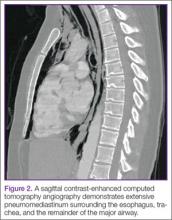

An assessment based on Well’s criteria showed the patient to be at a moderate risk for pulmonary embolism (PE), and a computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the chest was obtained. The CTA was negative for PE but showed significant pneumomediastinum (Figures 1 and 2). Upon repeat examination, crepitus was palpated on the anterior right neck, correlating with the CTA findings.

The patient was admitted to the inpatient ward for observation and continued support, and she was given IV analgesics and supplemental O2 via nasal cannula. Due to the considerable amount of air surrounding her heart, she was considered at high-risk for disease progression. Since she had been on continuous doxycycline therapy, the inpatient team performed a gastrografin swallow study to rule out esophageal perforation. The results of this test were negative, further supporting asthma exacerbation as the etiology for the pneumomediastinum. As cigarette smoking was a contributing risk factor, she was also counseled on tobacco cessation.

During her inpatient stay, the patient completed the 5-day course of oral corticosteroids that had been prescribed at her first ED visit, and was weaned-off supplemental O2. After an uncomplicated clinical course and full resolution of symptoms, she was discharged on hospital day 3 with an albuterol hydrofluoroalkane inhaler to be used as needed; she was also advised to continue taking doxycycline as prescribed for her dermatologic condition. The patient was followed in the outpatient setting on a routine basis; to date, she has remained asymptomatic with no sequelae.

Pneumomediastinum

Also referred to as mediastinal emphysema, pneumomediastinum manifests as free air surrounding the mediastinal structures.1-7 This condition most commonly occurs in middle-aged men; though rare, 25% of all cases have been linked to existing pulmonary disease.1,6,8,9 Patients with pneumomediastinum typically present with pleuritic chest pain (often radiating to the neck and back), dyspnea, dysphonia, and dysphagia.1,2,5,7-9

Risk Factors

Pneumomediastinum is usually associated with asthma exacerbations; however, it has also been linked to increases in intrathoracic pressure, extension of subcutaneous emphysema from superior structures (eg, cervical region), esophageal lesions, as well as use and/or withdrawal symptoms of certain drugs (eg, cocaine).1,2,4,6,8

When considering primary pulmonary disease, the pathophysiological process is driven by a pressure gradient between the pulmonary interstitium and the alveoli. The force transference causes alveolar rupture, allowing air to escape into the interstitium.9 In asthma, obstruction in the minor airways leads to air-trapping and barotrauma of distal airways, resulting in the aforementioned alveolar rupture.2 Once in the lung interstitium, the free air flows along the pressure gradient through the hilum from the pulmonary parenchyma in a centripetal direction before entering the mediastinum (Macklin effect).2,9

Pneumomediastinum is not exclusive to asthma and subsequent alveolar barotrauma. There are reported instances of gas-producing microorganisms within the mediastinum as well as perforated mucosal structures—specifically the esophagus (of which doxycycline is a risk factor) and tracheobronchial tree, which have also manifested as mediastinal emphysema.6,9