Existing resources. Consistently, the respondents verbalized the importance of acquiring knowledge and skills and using available resources in their disaster plan. They felt that training was critical and that it needed to be simple and uncomplicated. Many felt that they did not have sufficient drills to maintain their knowledge and skills for all types of events. One nursing assistant stated he had extensive training in the military in DM, but clinics did not have sufficient training and were not prepared to handle multiple casualties. Others stated that it would be important for training to be “second nature” so they would not have to think much about it, with everyone pulling together and performing tasks seamlessly. However, some stated that they did not know what to do in an emergency.

Critical resources noted were access to emergency power sources, transistor radios, telephone and communication, 911 services, backup phone services, computers, and text pagers and cell phones so that connections could be made outside the clinic setting. Other critical resources needed included medical supplies and access to food for 1 week.

Finally, teamwork was identified as a critical factor for success. One example involved the clinic responding to a severe snowstorm; the medical director, lead nurse, and support staff agreed to remain on site to assist with any patients who needed help. “We shared our 4-wheel drive trucks to get around, and others called patients, advising them of storm conditions and what to do to maintain care at home and canceled appointments scheduled for that day.” They were very proud of the way they had pooled their resources to support each other and their patients.

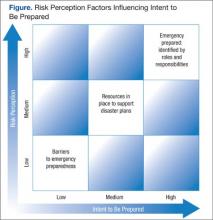

Based on these emerging themes and the inquiry guiding theories, a theoretical framework was proposed on how contributing factors influenced the process by which CBOC staff viewed their roles and the likelihood that they would participate in a disaster plan (Figure). The framework suggests that personal risks and perceived personal and clinic readiness to respond to an emergency were critical barriers to staff willingness to get involved in preparedness, whereas they saw the provision of training and resources as necessary to increase their resilience and ability to function in a disaster.

Clearly addressing barriers through training, planning, ensuring that resources functioned effectively in a disaster, and clarifying roles and responsibilities, combined with promoting personal and clinic readiness facilitated staff EP participation.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored issues surrounding the role of CBOCs in EP and how risk perception and enabling factors contributed to staff intent to participate in DM. As in many qualitative studies, findings were somewhat limited by an overall small sample size (N = 23) across 3 CBOCs in southern California. However, given the lack of available literature, the authors believe that this study helped provide critical insight into CBOC clinic staff’s willingness and readiness to be active in disaster response. The study clearly points to clinic staff’s openness to actively take part in regional disaster response and calls for better and more standardized approaches to EP and DM planning that include local CBOCs. The authors identified factors that contribute to staff intent to participate in DM and the need to reduce barriers that hinder participation.