Overdose deaths remain epidemic throughout the U.S. The rates of unintentional overdose deaths, increasing by 137% between 2000 and 2014, have been driven by a 4-fold increase in prescription opioid overdoses during that period.1-3

Veterans died of accidental overdose at a rate of 19.85 deaths/ 100,000 people compared with a rate of 10.49 deaths in the general population, based on 2005 data.4 There is wide state-by-state variation with the lowest age-adjusted opioid overdose death rate of 1.9 deaths/100,000 person-years among veterans in Mississippi and the highest rate in Utah of 33.9 deaths/100,000 person-years, using 2001 to 2009 data.5 These data can be compared with a crude general population overdose death rate of 10.6 deaths per 100,000 person-years in Mississippi and 18.4 deaths per 100,000 person-years in the general Utah population during that same period.6

Overdose deaths in the U.S. occur most often in persons aged 25 to 54 years.7 Older age has been associated with iatrogenic opioid overdose in hospitalized patients.8 Pulmonary, cardiovascular, and psychiatric disorders, including past or present substance use, have been associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose.9 However, veterans with substance use disorders are less likely to be prescribed opioids than are nonveterans with substance use disorders.10 Also, concomitant use of sedating medications, such as benzodiazepines (BZDs), can increase mortality from opioid overdose.11 Patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain conditions often take BZDs for various reasons.12 Veterans seem more likely to receive opioids to treat chronic pain but at lower average daily doses than the doses that nonveterans receive.10

Emergency management of life-threatening opioid overdose includes prompt administration of naloxone.13 Naloxone is FDA approved for complete or partial reversal of opioid-induced clinical effects, most critically respiratory depression.14,15 Naloxone administration in the emergency department (ED) may serve as a surrogate for an overdose event. During the study period, naloxone take-home kits were not available in the VA setting.

A 2010 ED study described demographic information and comorbidities in opioid overdose, but the study did not include veterans.16 The clinical characteristics of veterans treated for opioid overdose have not been published. Because identifying characteristics of veterans who overdose may help tailor overdose prevention efforts, the objective of this study is to describe clinical characteristics of veterans treated for opioid overdose.

Methods

A retrospective chart review and archived data study was approved by the University of Utah and VA institutional review boards, and conducted at the George E. Wahlen VAMC in Salt Lake City, Utah. This chart review included veterans who were admitted to the ED and treated with naloxone between January 1, 2009 and January 1, 2013.

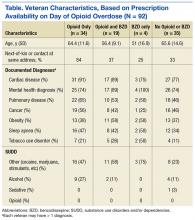

The authors used the Pharmacy Benefits Management Data Manager to extract data from the VA Data Warehouse and verified the data by open chart review (Table). The following data were collected: ED visit date (overdose date); demographic information, including age, gender, and race; evidence of next-of-kin or other contact at the same address as the veteran; diagnoses based on ICD-9 codes, including sleep apnea, obesitycardiac disease, pulmonary disease, mental health diagnoses (ICD-9 codes 290-302 [wild card characters (*) included many subdiagnoses]),

cancer, and substance use disorders and/or dependencies (SUDD); tobacco use; VA-issued prescription opioid and BZD availability, including dose, fill dates, quantities dispensed, and day supplies; specialty of opioid prescriber; urine drug screening (UDS) results; and outcome of the overdose.

No standardized research criteria identify overdose in medical chart review.17 For each identified patient, the authors reviewed provider and nursing notes charted during an ED visit that included naloxone administration. The event was included as an opioid overdose when notes indicated that the veteran was unresponsive and given naloxone, which resulted in increased respirations or increased responsiveness. Cases were excluded if the reason for naloxone administration was anything other than opioid overdose.

Medical, mental health, and SUDD diagnoses were included only if the veteran had more than 3 patient care encounters (PCE) with ICD-9 codes for a specific diagnosis entered by providers. A PCE used in the electronic medical record (EMR) helps collect, manage, and display outpatient encounter data, including providers, procedure codes, and diagnostic codes. Tobacco use was extracted from health factors documented during primary care visit screenings. (Health factors help capture data entered in note templates in the EMR and can be used to query trends.) A diagnosis of obesity was based on a calculated body mass index of > 30 kg/m2 on the day of the ED visit date or the most recently charted height and weight. The type of SUDD was stratified into opioids (ICD-9 codes 304.0*), sedatives (ICD-9 code 304.1*), alcohol (ICD-9 code 303.*), and other (ICD-9 codes 304.2-305.9).

The dosage of opioids and BZDs available to a veteran was determined by using methods similar to those described by Gomes and colleagues: the dose of opioids and BZDs available based on prescriptions dispensed during the 120 days prior to the ED visit date and the dose available on the day of the ED visit date if prescription instructions were being followed.18 Prescription opioids and BZDs were converted to daily morphine equivalent dose (MED) and daily lorazepam-equivalent dose (LED), using established methods.19,20

Veterans were stratified into 4 groups based on prescribed medication availability: opioids only, BZDs only, opioids and BZDs, and neither opioids nor BZDs. The specialty of the opioid prescribers was categorized as primary care, pain specialist, surgeon, emergency specialist, or hospitalist (discharge prescription). Veteran EMRs contain a list of medications obtained outside the VA facility, referred to as non-VA prescriptions. These medications werenot included in the analysis because accuracy could not be verified.

A study author reviewed the results of any UDS performed up to 120 days before the ED visit date to determine whether the result reflected the currently prescribed prescription medications. If the UDS was positive for the prescribed opioids and/or BZDs and for any nonprescribed drug, including alcohol, the UDS was classified as not reflective. If the prescribed BZD was alprazolam, clonazepam, or lorazepam, a BZD-positive UDS was not required for the UDS to be considered reflective because of the sensitivity of the UDS BZD immunoassay

used at the George E. Wahlen VAMC clinical laboratory.21

Outcomes of the overdose were categorized as discharged, hospitalized, or deceased. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. Group comparisons were performed using Pearson chi-square or Student t test.