Epidemiology

The prevalence rates for PTSD are increasing in the military, possibly stemming from the demands on service members engaged in years’ long wars. Despite the increased attention on this phenomenon, research has demonstrated that the majority of service members who deploy do not develop PTSD or significant trauma-related functional impairment.10 Furthermore, many cases of PTSD diagnosed in the MHS stem from traumatic experiences other than combat exposure, including childhood abuse and neglect, sexual and other assaults, accidents and health care exposures, domestic abuse, and bullying. Depression arguably has received less attention despite comparable prevalence rates in military populations, high co-occurrence of PTSD and depression, and depression being associated with a greater odds ratio for mortality that includes death by suicide in military service members.11

Estimates of the prevalence of PTSD from the U.S. Army suggest that it exists in 3% to 6% of military members who have not deployed and in 6% to 25% of service members with combat deployment histories. The frequency and intensity of combat are strong predictors of risk.7 A recent epidemiologic study using inpatient and outpatient encounter records showed that the prevalence of PTSD in the active military component was 2.0% in the middle of calendar year (CY) 2010; a two-thirds increase from 1.2% in CY 2007.12 The incidence of PTSD

diagnoses likewise increased by one-fifth, from 0.81% to 0.97%, over the same period.Epidemiologic studies and prevalence/incidence rates derived from administrative data rely on strict case definitions. Consequently, such administrative investigations include data only from service members

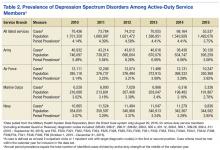

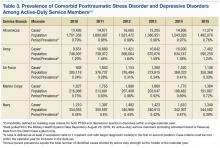

engaged in or identified by the medical system. Although these rates describe a lower limit for diagnostic prevalence, they serve as a good starting point to ascertain trends. Keeping in mind the limitations of administrative epidemiology, the MHS has witnessed a steady upward trend in comorbid cases of PTSD and depression since 2010. On average, between 2010 and 2015, patients diagnosed with PTSD were twice as likely to have a comorbid depression spectrum disorder diagnosis (42.4%) than depression spectrum disorder patients were to have a comorbid PTSD diagnosis (20.8%). Period prevalence for PTSD, depressive spectrum disorders, and comorbid disorders are described in Tables 1-3.PTSD and Depression Treatment

Despite the high rates of PTSD and MDD comorbidity, few treatments have been developed for and tested on an exclusively comorbid sample of patients.13 However, psychopharmacologic agents targeting depression have been applied to the treatment of PTSD, and PTSD psychotherapy trials typically include depression response as a secondary outcome. The generalizability of findings to a truly comorbid population may be limited based on study sampling frames and the unique characteristics of patients with comorbid PTSD and depression.14-16 Several psychopharmacologic treatments for depression have been evaluated as frontline treatments for PTSD. The 3 pharmacologic treatments that demonstrate efficacy in treating PTSD include fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine.17

Although these pharmacologic agents represent good candidate treatments for comorbid patients, the effect size of pharmacologic treatments are generally smaller than those of psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD.17,18 This observation, however, is based on indirect comparisons, and a recent systematic review concluded that the evidence was insufficient to determine the comparative effectiveness between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for PTSD.19 Evidence indicates that trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies consistently demonstrate efficacy and effectiveness in treating PTSD.19,20 These treatments also have been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms among PTSD samples.21

Based on strong bodies of evidence, these pharmacologic and psychological treatments have received the highest level of recommendation in the VA and DoD.22,23 Accordingly, both agencies have invested considerable resources in large-scale efforts to improve patient access to these particular treatments. Despite these impressive implementation efforts, however, the limitations of relying exclusively on these treatments as frontline approaches within large health care systems have become evident.24-26

Penetration of Therapies

Penetration of these evidence-based treatments (EBTs) within the DoD and VHA remains limited. For instance, one study showed that VA clinicians in mental health specialty care clinics may provide only about 4 hours of EBT per week.27

Other reports suggest that only about 60% of treatment-seeking patients in PTSD clinics receive any type of evidence-based therapy and that within-session care quality is questionable based on a systematic review of chart notes.28,29 Attrition in trauma-focused therapy is a recognized limitation, with 1 out of 3 treatment-seeking patients not completing a full dose of evidence-based treatment.30-33 Large-scale analyses of VHA and DoD utilization data suggest that the majority of PTSD patients do not receive a sufficient number of sessions to be characterized as an adequate dose of EBT, with a majority of dropouts occur- ring after just a few sessions.34-37

Hoge and colleagues found that < 50% of soldiers meeting criteria for PTSD received any mental health care within the prior 6 months with one-quarter of those patients dropping out of care prematurely.38 Among a large cohort of soldiers engaged in care for the treatment of PTSD, only about 40% received a number of EBT treatment sessions that could qualify as an adequate dose.38 Thus, although major advancements in the development and implementation of effective treatments for PTSD and depression have occurred, the penetration of these treatments is limited, and the majority of patients in need of treatment potentially receive inadequate care.39

System level approaches that integrate behavioral health services into the primary care system have been proposed to address these care gaps for service members and veterans.40-42 Fundamentally, system-level approaches seek to improve the reach and effectiveness of care through large-scale screening efforts, a greater emphasis on the quality of patient care, and enhanced care continuity across episodes of treatment.