Arrangements are made to have a mail courier present during the removal of the liner. Once removed, the liner is immediately sealed and released to the mail courier who transports the liner to the DEA authorized reverse distributor. The reverse distributor is a licensed entity that has the authority to take control of the medications, including controlled substances, for disposal. The liner tracking numbers are kept in a police log book so that delivery can be confirmed and destruction certificates obtained from the vendor’s website at a later date. The records are kept for 3 years.

Funding was obtained for a 38-gallon collection receptacle and 12 liners from Pharmacy Benefits Management Services (PBM). Approval was obtained from RLRVAMC leadership to locate the receptacle in a high-traffic area, anchored to the floor, under video surveillance, and away from the ED entrance (a DEA requirement). Public Affairs promoted the receptacle to veterans. E-mails were sent to staff to provide education on regulatory requirements. Weight and frequency of medications returned were obtained from data collected by the reverse distributor. Descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

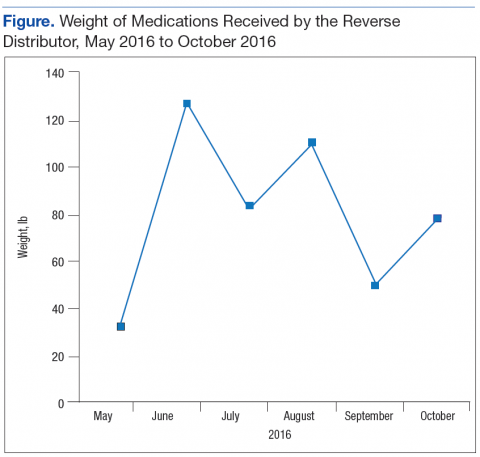

The Federal Supply Schedule cost to procure a DEA-compliant receptacle was $1,450. The additional 12 inner liners cost $2,024.97. 8 Staff from Engineering Service were able to install the receptacle at no additional cost to the facility. The collection receptacle was opened to the public in May 2016. From May through October 2016, the facility collected and returned 10 liners to the reverse distributor containing 452 lb of medications. An additional 30 lb of drugs were returned through the mailback envelope program for a total weight of 482 lb over the 6-month period (Figure). The average time between inner liner changes was 2.6 weeks.

Discussion

The most challenging aspect of implementation was identification of a location for the receptacle. The location chosen, an alcove in the hallway between the coffee shop and outpatient pharmacy, was most appropriate. It is a high-traffic area, under video surveillance, and provides easy access for patients. Another challenge was determining the frequency of liner changes. There was no historic data to assist with predicting how quickly the liner would fill up. Initially, Police Service checked the receptacle every week, and it was emptied about every 2 weeks. Aspatients cleaned out their medicine cabinets, the liner needed to be replaced closer to every 4 weeks. An ongoing challenge has been determining how full the liner is without requiring the police to open the receptacle. Consideration is being given to installing a scale in the receptacle under the liner and having the display affixed to the outside of the container.

The receptacle seemed to be the preferred method of disposal, considering that it generated nearly 15 times more waste than did the mail-back envelopes during the same time period. Anecdotal patient feedback has been extremely positive on social media and by word-of-mouth.

Limitations

One limitation of this disposal program is that the specific amount of controlled substance waste vs noncontrolled substance waste cannot be determined since the liner contents are not inventoried. The University of Findlay in Ohio partnered with local law enforcement to host 7 community medication take-back events over a 3-year period, inventoried the drugs, and found that about one-third of the dosing units (eg, tablet or capsule) returned in the analgesic category were controlled substances, suggesting that take-back events may play a role in reducing unauthorized access to prescription painkillers. 9 By witnessing the changing of inner liners, it can be anecdotally confirmed that a significant amount of controlled substances were collected and returned at RLRVAMC. These results have been shared with respective VISN leadership, and additional facilities are installing receptacles.