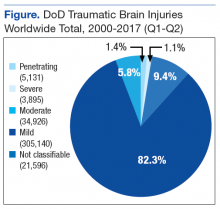

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a health concern for the U.S. Military Health System (MHS) as well as the VHA. It occurs in both deployed and nondeployed settings; however, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and improved reporting mechanisms have dramatically increased TBI diagnoses in active-duty service members. According to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC), more than 370,000 service members have been diagnosed with a TBI since 2000 (Figure).1

Background

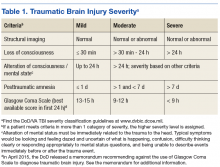

The DoD and the VA are collaborating on clinical research studies to identify, understand, and treat the long-term effects of TBI that can affect patients and their families. Most TBIs are mild (mTBIs), also called concussions, and patients typically recover within a few weeks (Table 1). However, some individuals with mTBI experience symptoms that may persist for months or years. A meta-analysis by Perry and colleagues showed that the prevalence or risk of a neurologic disorder, depression, or other mental health issue following mTBI was 67% higher compared with that in uninjured controls.2

Patients with any severity of TBI may require assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, dressing, managing medications, and feeding. Patients also may need help with instrumental ADLs, such as meal preparation, grocery shopping, household chores, child care, getting to appointments or activities, coordination of educational and vocational services, financial and benefits management, and supportive listening.

Increased injuries have spurred the DoD and VA to coordinate health care to provide a seamless transition for patients between the 2 agencies. However, individuals who sustained a TBI may need various levels of caregiver assistance over time.

TBI and Caregivers

Despite better agency coordination for patients, caregivers can experience stress. Griffin and colleagues found that caregiving responsibilities can compete with other demands on the caregiver, such as work and family, and may negatively impact their health and finances.3,4

Lou and colleagues studied the factors associated with caring for chronically ill family members that may result in stress for the caregivers.5 Along with an unaccounted for economic contribution, caregivers may face lost work time and pay and limitations on work travel and work advancement. Additionally, lost time for leisure, travel, social activities, family obligations, and retirement could result in physical and mental drain on the caregiver. Stress may reach a level at which the caregivers risk psychological distress. The study also noted that families with perceived high stress experience disrupted family functioning. Some TBI caregiver studies sought to understand how best to evaluate and determine the level of caregiver burden, and other studies investigated appropriate interventions.6-9

Health care practitioners within the federal health care system may benefit from a greater awareness of caregiver needs and caregiver resources. Caregiver support can improve outcomes for both the caregiver and care recipient, and many organizations and resources already exist to assist the caregiver. This article reviews recent published literature on TBI caregivers of patients with TBI across civilian, military, and veteran populations and lists caregiver resources for additional information, assistance, and support.

Literature Review

The DVBIC defines the term caregiver as “any family or support person(s) relied upon by the service member or veteran with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who assumes primary responsibility for ensuring the needed level of care and overall well-being of that service member or veteran. A family or family caregiver may include spouse, parents, children, other extended family members, as well as significant others and friends.”3

In the following discussion, findings from military and veteran literature are separated from civilian population findings to highlight similarities and differences between these 2 bodies of research. Several of the studies in the military/veteran cohorts include polytrauma patients with comorbid physical and mental health issues not necessarily found in civilian literature.

Civilian Literature

A 2015 systematic review by Anderson and colleagues on coping and psychological adjustment in TBI caregivers indicated no Class I or Class II studies.10 Four Class III and 3 Class IV studies were found. The authors suggest that more rigorous studies (ie, Class I and II) are needed.

Despite these limitations, peer-reviewed literature indicates that the levels of stress and distress in TBI caregivers are consistent with reports for other diseases. In a civilian population, Carlozzi and colleagues found that TBI caregivers who reported stress, distress, anxiety, and feeling overwhelmed often had concerns for their social, emotional, physical, cognitive health, as well as feelings of loss.5 In addition, caregivers may need to take leaves of absence or leave the workforce entirely to provide for a family member or friend who had a TBI—often leading to financial strain (eg, depleting assets, accumulating debt). These challenges may occur during prime earning years, and the caregiver may lose the ability to resume work if the care receiver requires care for extended periods.11

Kratz and colleagues showed that caregivers of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI: (1) felt overburdened with responsibilities; (2) lacked personal time and time for self-care; (3) felt their lives were interrupted or lost; (4) grieved the loss of the person with TBI; and (5) endorsed anger, guilt, anxiety, and sadness.12

Perceptions differed between caregiver parents and caregiver partners. Parents expressed feelings of grief and sadness related to the “loss of the person before the TBI.” Parents also reported a sense of guilt and responsibility for their child’s TBI and feelings of being tied down to the individual with TBI. Parents experienced a greater level of stress if the son or daughter with TBI still lived at home. Partners expressed frustration and despair related to their role as sole decision maker and care provider. Partners’ distress also related to the partner relationship and the relationship between children and the individual with TBI.

Verhasghe and colleagues found that partners experience a greater degree of stress than do parents.13 Young families with minimal social support for coping with financial, psychiatric, and medical problems were the most vulnerable to stress. A systematic review by Ennis and colleagues evaluated depression and anxiety in caregiver parents vs spouses.14 Although methods and quality differed in the studies, findings indicated high levels of distress regardless of the type of caregiver.

Anderson and colleagues used the Ways of Coping Questionnaire to evaluate the association between coping and psychological adjustment in caregivers of TBI individuals.10 The use of emotion-focused coping and problem solving was possibly associated with psychological adjustment in caregivers. Verhasghe and colleagues indicated that the nature of the injuries more than the severity of TBI determined the level of stress up to 15 years after the TBI.13 Gender and social and professional support also influenced coping. The review identified the need to develop models of long-term support and care.

An Australian cohort of 79 family caregivers participated in a study by Perlesz and colleagues.15 Participants’ caregiving responsibilities averaged 19.3 months posttrauma. The Family Satisfaction Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, State Anxiety Inventory, and Profile of Mood States were used in this analysis. Male caregivers reported distress in terms of anger and fatigue; female caregivers were at greatest risk of poor psychosocial outcomes. Although findings from primary caregivers indicated that 35% to 49% displayed enough distress to warrant clinical intervention, between 51% and 80% were not psychologically distressed and were satisfied with their families. Data supported previous reports suggesting caregivers are “not universally distressed.”15

Manskow and colleagues followed patients with severe TBI and assessed caregiver burden 1 year later. Using the Caregiver Burden Scale, caregivers reported the highest scores (N = 92) on the General Strain Index followed by the Disappointment Index.16 Bayen and colleagues also studied caregivers of severe TBI patients.17 Objective and subjective caregiver burden data 4 years later indicated 44% of caregivers (N = 98) reported multidimensional burden. Greater burden was associated in caring for individuals who had poorer Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended scores and more severe cognitive disorders.