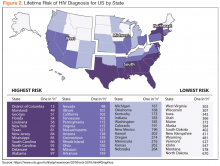

The majority of the VHA patient population is male (91% in 2016).14 A VHA analysis of PrEP initiations in the VA indicates that in June 2017, 97% of veterans in VA care receiving PrEP were male, 69% were white, 88% resided in urban areas, and the average age was 41.6 years. An analysis of PrEP initiation in the VA indicates that current PrEP uptake is clustered in a few geographic areas and that some areas with high HIV incidence had low uptake.15 States with the highest risk of HIV infection are in the Southeast, followed by parts of the West, Midwest, and Northeast (Figure 2).16,17

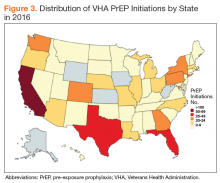

In 2016, California accounted for the largest absolute number of PrEP prescriptions in the VA, followed by Texas and Florida (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with 2014 non-VA data, which found that the majority of PrEP recipients lived in metropolitan areas with almost half (43%) living in the West.18 The VA’s goal is to better align PrEP uptake across the country with regional HIV epidemiology.Rural areas are increasingly impacted by the HIV epidemic in the US, but access to PrEP is often limited in rural communities.19 Several rural counties in the Southeastern US now have rates of new HIV infection comparable with those historically seen in only the largest cities.1 In addition, recent outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C virus infection related to needle sharing highlight the need for HIV prevention programs in rural areas impacted by the opioid epidemic.20

About 1 in 4 veterans overall—and 16% of veterans in care who are HIV-positive—reside in rural areas, but only 4.3% of veterans who had initiated PrEP through 2017 resided in rural areas.21,22 In order to address the need to improve access to PrEP in many rural-serving VHA facilities, the PrEP Working Group has emphasized the increased utilization of virtual care (telehealth, Annie App, the Virtual Medical Room) and broadening the pool of available PrEP prescribers to include noninfectious diseases physicians, pharmacists, and APRNs.

Important racial and ethnic disparities also exist in PrEP access nationally. For example, in the US as a whole, African American MSM, followed by Latino MSM continue to be at highest risk for HIV infection.1 In 2015, 45% of all new HIV infections in the US were among African Americans, 26% of whom were women and 58% identified as gay or bisexual.23 A recent analysis of US retail pharmacies that dispensed FTC/TDF analyzed the racial demographics of PrEP uptake and found that the majority of PrEP initiations were among whites (74%), followed by Hispanics (12%) and African Americans (10%); and females of all races made up 20.7%.24 The VA is performing better than these national averages. Of the 688 PrEP prescriptions in the VA in 2016, 64% of recipients identified themselves as white and 23% as African American. Hispanic ethnicity was reported by 13%.

There are several limitations to identifying a specific implementation target for PrEP across the VA system, including the challenge of accurately identifying the population at risk via the EHR or clinical informatics tools. For example, strong risk factors for HIV acquisition include IV drug use, receptive anal intercourse without a condom, and needlesticks.

Behaviors that pose lower risk, such as vaginal intercourse or insertive anal intercourse could contribute to a higher overall lifetime risk if these behaviors occur frequently.25 Behavioral risk factors are not well captured in the VA EHR, making it difficult to identify potential PrEP candidates through population health tools. Additionally, stigma and discrimination may make it difficult for a patient to disclose to their clinician and for a clinician to inquire into behavioral risk factors. The criminalization of HIV-related risk behaviors in some states also may complicate the identification of potential PrEP candidates.26,27 These issues contribute to the challenges that providers face in screening for HIV risk and that patients face in disclosing their personal risk.

To address these regional, rural, and ethnic disparities and enhance the identification of potential PrEP recipients, the National PrEP Working Group is developing a suite of tools to support frontline providers in identifying potential PrEP recipients and expanding care to those at highest risk and who may be more difficult to reach due to rurality, concerns about stigma, or other issues.

These include the following:- Clinical support tools to identify potential PrEP recipients, such as a clinical reminder that identifies patients at high risk for HIV based on diagnosis codes, and a PrEP clinical dashboard;

- A telehealth protocol for PrEP care and promotion of the VA Virtual Medical Room, which allows providers to video conference with patients in their home; and

- Social media outreach and awareness campaigns targeted at veterans to increase PrEP awareness are being shared through VA Facebook and Twitter accounts, blog posts, and www.hiv.va.gov posts (Figure 4).