Results

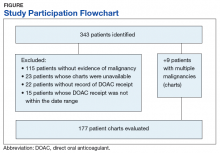

From initial FDA approval of dabigatran (first DOAC on the market) on October 15, 2012, to January 1, 2017, there were 343 patients who met initial inclusion criteria. Of those, 115 did not have any clear evidence of malignancy, 22 did not have any records of DOAC receipt, 15 did not receive a DOAC within the date range, and 23 patients’ charts were unavailable.

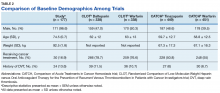

In addition, 9 of the patients identified had multiple malignancies. This resulted in 177 evaluable medical charts for this study (Figure).The majority of the patients were males (96.6%), with an average age of 74.5 years. The average weight of all patients was 92.5 kg, with an average SCr of 1.1 mg/dL. This equated to an average CrCl of 85.5 mL/min based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation using actual bodyweight. Of the 177 patients evaluated, 30 (16.9%) were receiving active cancer treatment at time of DOAC initiation.

Ninety patients (50.8%) received apixaban, 53 patients (29.9%) received dabigatran, and 34 patients (19.2%) received rivaroxaban; no patients received edoxaban therapy. Most of the patients (79.1%) received a DOAC for stroke prevention with AF/atrial flutter, and the remainder received a DOAC for VTE treatment (12.4%) or VTE prophylaxis due to a history of prior VTE (8.5%). Baseline demographics are presented in Table 1 and are compared with the baseline demographics from the CLOT and CATCH trials in Table 2.Two (1.1%) patients developed a VTE while receiving a DOAC.

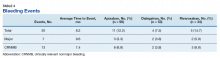

One patient was on rivaroxaban 20 mg daily for a prior VTE; the other was on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily for stroke prevention due to AF. Both patients developed a DVT, which was diagnosed by ultrasound (Table 3). The rate of VTE incidence in the CLOT trial was 8% and in the CATCH trial was 7.2%, both of which were much higher than the rate reported in this study (P < .01).9,10Among the 177 evaluable patients in this study, there were 7 patients (4%) who developed a major bleed and 13 patients (7.3%) who developed a clinically relevant nonmajor bleed according to the definitions provided by ISTH.11

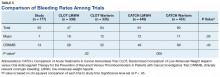

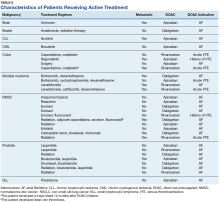

The average time from first DOAC prescription to the bleeding event was about 9.6 months for a major bleed and 7.4 months for a CRNMB. Of the patients who had a major bleed, 3 were receiving apixaban,2 were receiving dabigatran, and 2 were receiving rivaroxaban (P = .79 for all DOACs). Of the patients who developed CRNMB, 8 were receiving apixaban, 2 were receiving dabigatran, and 3 were receiving rivaroxaban (P = .88 for all DOACs). The breakdown of bleeding rates is presented in Table 4. The comparison of major and CRNMB rates in this study and the landmark trials are presented in Table 5.As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients were actively receiving treatment during DOAC administration. Most of the documented cases of malignancy were either a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) or prostate cancer. The most common method of treatment was surgical resection for both malignancies. Of the 30 patients who received active malignancy treatment while on a DOAC, there were 4 patients with multiple myeloma, 6 patients with NMSC, 4 patients with colon cancer, 1 patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 1 patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), 1 patient with small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL), 4 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 1 patient with unspecified brain cancer, and 1 patient with breast cancer. The various characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 6.

Among these 30 patients, only 1 patient developed a DVT. Another patient developed a major bleed 12 months after initiating rivaroxaban 20 mg daily due to a history of prior VTE.Discussion

The CLOT and CATCH trials were chosen as historic comparators. Although the active treatment interventions and comparator arms were not similar between the patients included in this study and the CLOT and CATCH trials, the authors felt the comparison was appropriate as these trials were designed specifically for patients with malignancy. Additionally, these trials sought to assess rates of VTE formation and bleeding in the patient with malignancies—outcomes that aligned with this study. Alternative trials for comparison are the subgroup analyses of patients with malignancies in the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials.12-14 Although these trials were designed to stratify patients based on presence of malignancy, they were not powered to account for increased risk of VTE in patients with malignancies.

There are multiple risk factors that increase the risk of CAT. Khoranna and colleagues identified primary stomach, pancreas, brain, lung, lymphoma, gynecologic, bladder, testicular, and renal carcinomas as a high risk of VTE formation.15 Additionally, Khoranna and colleagues noted that elderly patients and patients actively receiving treatment are at an increased risk of VTE formation.15 The low rate of VTE formation (1.1%) in the patients in this study may be due to the low risk for VTE formation. As previously mentioned, only 30 of the patients (16.9%) in this study were receiving active treatment.

Additionally, there were only 42 patients (23.7%) who had a high-risk malignancy. The increased age of the patient population (74.5 years old) in this study is one risk factor that could largely skew the risks of VTE formation in the patient population. In addition to age, the average body mass index (BMI) of this study’s patient population (30 kg/m2) may further increase risk of VTE. Although Khoranna and colleagues identified a BMI of 35 kg/m2 as the cutoff for increased risk of CAT, the increased risk based on a BMI of 30 kg/m2 cannot be ignored in the patients in this study.15

Another risk inherent in the treatment of patients with cancer is pancytopenia, which may lead to increased risks of bleeding and infection. When patients are exposed to an anticoagulant agent in the setting of decreased platelets and hemoglobin (from treatment or disease process), the risk for major bleeds and CRNMB are increased drastically. In this patient population, the combined rate of bleeding (11.3%) was relatively decreased compared with that of the CLOT (16.5% for all bleeding events) and CATCH (15.7% for all bleeding events) trials.9,10

Compared with the oncology subgroup analysis of the AMPLIFY, RE-COVER, and EINSTEIN trials, the differences are more noticeable. The AMPLIFY trial reported a 1.1% incidence of bleeding in patients with cancer on apixaban, whereas the RE-COVER trial did not report bleeding rates, and the EINSTEIN trial reported a 14% incidence of bleeding in all patients with cancer on rivaroxaban for VTE treatment.12-14 This study found a bleeding incidence of 12.2% with apixaban, 5.7% with dabigatran, and 14.7% with rivaroxaban. In this trial the incidence of bleeding with rivaroxaban were similar; however, the incidence of bleeding with apixaban was markedly higher. There is no obvious explanation for this, as the dosing of apixaban was appropriate in all patients in this trial except for one. There was no documented bleed in this patient’s medical chart.

A meta-analysis conducted by Vedovati and colleagues identified 6 studies in which patients with cancer received either a DOAC (with or without a heparin product) or vitamin K antagonist.16 That analysis found a nonsignificant reduction in VTE recurrence (odds ratio [OR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31-1.1), major bleeding (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.41-1.44), and CRNMB (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.62-1.18).16 The meta-analysis adds to the growing body of evidence in support of both safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with cancer. Although the Vedovati and colleagues study does not directly compare rates between 2 treatment groups, the findings of similar rates of VTE recurrence, major bleed, and CRNMB are consistent with the current study. Despite differing patient characteristics, the meta-analysis by Vedovati and colleagues supports the ongoing use of DOACs in patients with malignancy, as does the current study.16