A hospitalist developed and implemented a 4-week interprofessional curriculum for all clinical trainees and students, which occurs continuously. The curriculum includes a monthly academic conference and 12 didactic lectures and is taught by 16 interprofessional faculty from the TCU and the Palliative Care/Hospice Unit, including medicine, geriatric and palliative care physicians, physician assistants, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, pharmacists, and a geriatric psychologist. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfers between clinical settings as well as education in transitional care. In addition, using a team of interprofessional faculty, the curriculum develops the interprofessional competencies of teamwork and communication. The curriculum also has provided a significant opportunity for interprofessional collaboration among faculty who have volunteered their teaching time in the development and teaching of the curriculum, with potential for improved clinical staff knowledge of other disciplines.

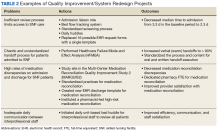

Quality improvement and system redesign projects in care transitions also have expanded (Table 2).

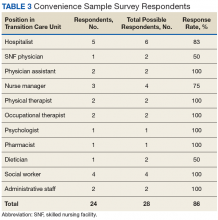

Recent initiatives include the redesign of the admissions screening process, which shortened the average review time from 3 days to 2 days, and a “safe handoff” healthcare failure mode and effect analysis (HFMEA).12 This HFMEA focused on improving the transfer process for veterans moving from the acute inpatient setting to the TCU. Interprofessional team members from both the acute care hospital and SNF staff collaborated to standardize the process and content for both oral and written handoff execution. Another example of the robust QI activities recently undertaken in this setting is the establishment of the TCU as a participant site in a Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study 2 (MARQUIS2), an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded study in medication reconciliation.13 The study includes 18 sites nationally; the TCU is the only non-hospital and transitional care site. Preliminary results show clinically meaningful reductions in unintentional medication discrepancies in this setting.Early assessment indicates that the new staffing model is having positive effects on the clinical environment of the TCU. A survey was conducted of a convenience sample of all physicians, nurse managers, social workers, and other members of the clinical team in the TCU (N=24)(Table 3), with response categories ranging on a Likert scale from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive).

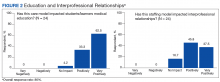

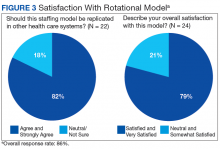

Respondents indicated that the staffing model was having positive influences on clinical skills and knowledge (4.4) and patient care (4.0). In addition, respondents reported positive impact on interprofessional relationships (4.2), development of education opportunities (4.6), and high overall satisfaction with the staffing model (4.1). Approximately 4 of 5 respondents (82%) expressed agreement with the notion of replicating this staffing model in other health care systems (Figures 1, 2 and 3). The subset of responses, including only hospitalists found similar favorable results.Although not rigorously analyzed using qualitative research methods, comments from respondents have consistently indicated that this staffing model increases the transfer of clinical and logistical knowledge among staff members working in the acute inpatient facility and the TCU.

This cross-pollination is believed to improve the safety of care for patients transferring between the 2 settings, as both the hospital and the SNF now have physicians with a detailed understanding of each setting’s capabilities and needs and disseminate this information to other clinicians. Many respondents have noted that the new model has fostered collaboration across care spectrums, thereby improving interdisciplinary learning, communication, and teamwork among clinicians as well as learners.