Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major health concern that can cause significant disability as well as economic and social burden. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 58% increase in the number of TBI-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths from 2006 to 2014.1 In the CDC report, falls and motor vehicle accidents accounted for 52.3% and 20.4%, respectively, of all civilian TBI-related hospitalizations. In 2014, 56,800 TBIs in the US resulted in death. A large proportion of severe TBI survivors continue to experience long-term physical, cognitive, and psychologic disorders and require extensive rehabilitation, which may disrupt relationships and prevent return to work.2 About 37% of people with mild TBI (mTBI) cases and 51% of severe cases were unable to return to previous jobs. A study examining psychosocial burden found that people with a history of TBI reported greater feelings of loneliness compared with individuals without TBI.3

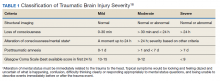

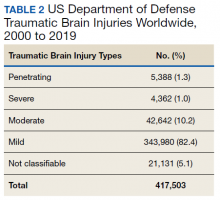

Within the US military, the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) indicates that > 417,503 service members (SMs) have been diagnosed with TBI since November 2000.4 Of these, 82.4% were classified as having a mTBI, or concussion (Tables 1 and 2). The nature of combat and military training to which SMs are routinely exposed may increase the risk for sustaining a TBI. Specifically, the increased use of improvised explosives devices by enemy combatants in the recent military conflicts (ie, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn) resulted in TBI being recognized as the signature injury of these conflicts and brought attention to the prevalence of concussion within the US military.5,6 In the military, the effects of concussion can decrease individual and unit effectiveness, emphasizing the importance of prompt diagnosis and proper management.7

Typically, patients recover from concussion within a few weeks of injury; however, some individuals experience symptoms that persist for months or years. Studies found that early intervention after concussion may aid in expediting recovery, stressing the importance of identifying concussion as promptly as possible.8,9 Active treatment is centered on patient education and symptom management, in addition to a progressive return to activities, as tolerated. Patient education may help validate the symptoms of some patients, as well as help to reattribute the symptoms to benign causes, leading to better outcomes.10 Since TBI is such a relevant health concern within the DoD, it is paramount for practitioners to understand what resources are available in order to identify and initiate treatment expeditiously.

This article focuses on the clinical tools used in evaluating and treating concussion, and best practices treatment guidelines for health care providers (HCPs) who are required to evaluate and treat military populations. While these resources are used for military SMs, they can also be used in veteran and civilian populations. This article showcases 3 DoD clinical tools that assist HCPs in evaluating and treating patients with TBI: (1) the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation 2 (MACE 2); (2) the Progressive Return to Activity (PRA) Clinical Recommendation (CR); and (3) the Concussion Management Tool (CMT). Additional DoD clinical tools and resources are discussed, and resources and links for the practitioner are provided for easy access and reference.