Case Presentation: A 45-year-old US Coast Guard veteran with a medical history of asthma and chronic back pain was referred to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of progressive, unexplained dyspnea. Two years prior to presentation, the patient was an avid outdoorsman and highly active. At the time of his initial primary care physician (PCP) evaluation he reported dyspnea on exertion, and symptoms consistent with an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and a recent tick bite with an associated rash. He was treated with intranasal fluticasone and a course of antibiotics. His URTI symptoms and rash improved; however the dyspnea persisted and progressed over the ensuing winter and he was referred for pulmonary function testing. Additional history included a 20 pack-year history of smoking (resolved 10 years prior to the first VABHS clinical encounter) and a family history of premature coronary artery disease (CAD) in his father and 2 paternal uncles. He lived in northern New England where he previously worked as a cemetery groundskeeper.

►Kristopher Clark, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston University/Boston Medical Center: Dr. Goldstein, how do you approach a patient who presents with progressive dyspnea?

►Ronald Goldstein, MD, Chief of Pulmonary and Critical Care VABHS: The evaluation of dyspnea is a common problem for pulmonary physicians. The sensation of dyspnea may originate from a wide variety of etiologies that involve pulmonary and cardiovascular disorders, neuromuscular impairment, deconditioning, or psychological issues. It is important to characterize the temporal pattern, severity, progression, relation to exertion or other triggers, the smoking history, environmental and occupational exposures to pulmonary toxins, associated symptoms, and the history of pulmonary problems.1

The physical examination may help to identify an airway or parenchymal disorder. Wheezing on chest examination would point to an obstructive defect and crackles to a possible restrictive problem, including pulmonary fibrosis. A cardiac examination should be performed to assess for evidence of heart failure, valvular heart disease, or the presence of loud P2 suggestive of pulmonary hypertension (PH). Laboratory studies, including complete blood counts are indicated.

A more complete pulmonary evaluation usually involves pulmonary function tests (PFTs), oximetry with exertion, and chest imaging. Additional cardiac testing might include electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac echocardiogram, followed by an exercise study, if needed. A B-natriuretic peptide determination could be considered if there is concern for congestive heart failure.2

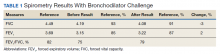

►Dr. Clark: The initial physical examination was normal and laboratory tests were unrevealing. Given his history of asthma, he underwent spirometry testing (Table 1).

Dr. Goldstein, aside from unexplained dyspnea, what are other indications for spirometry and when should we consider ordering a full PFT, including lung volumes and diffusion capacity? Can you interpret this patient’s spirometry results?

►Dr. Goldstein: Spirometry is indicated to evaluate for a suspected obstructive defect. The test is usually performed with and without a bronchodilator to assess airway reactivity. A change in > 12% and > 200 mL suggests acute bronchodilator responsiveness. Periodic spirometry determinations are useful to assess the effect of medications or progression of disease. A reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) may suggest a restrictive component. This possibility requires measure of lung volumes.