Prior to implementation, the PADR template was introduced to HCPs at 2 chief-of-medicine rounds on the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism by a pharmacist and endocrinologist. These educational sessions used case examples and discussions to teach the appropriate use of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism. The target audience was PCPs, residents, and other specialists who might prescribe testosterone.

Retrospective Chart Review

To assess the impact of the new testosterone order template on adherence to OIG recommendations, a retrospective chart review was completed comparing the appropriateness of initiating testosterone replacement therapy pretemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2018) vs posttemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2019). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were modeled after the 2018 OIG report to allow for comparison with the OIG study population. Eligible veterans in each time period included males who received a new testosterone prescription without having been prescribed testosterone in the previous 12 months. Exclusion criteria included community care network prescriptions (CCNRx); current testosterone prescription from a different VA site; clinic administration of testosterone in the previous 12 months; an organic hypogonadism (ie, Klinefelter syndrome) or gender dysphoria diagnosis; and whether the testosterone prescription was never dispensed (PADR was denied or veteran never had the prescription filled). Veterans who met the inclusion criteria in CPRS were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

Determining the appropriateness of testosterone prescribing, such as symptoms and laboratory measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypogonadism, was based on the OIG report and Endocrine Society guidelines. A chart review of the 12 months before testosterone prescribing was completed for each veteran, assessing for documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency and laboratory measurements of serum testosterone, LH, and FSH. Also, documentation of a discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy in the 3 months before prescribing was assessed, which matched the timeframe in the VA OIG report.

Interim Analysis

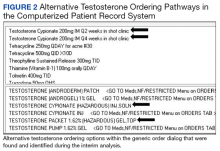

After initial template implementation, the multidisciplinary workgroup reconvened for a preplanned interim analysis in November 2019. The evaluation at this meeting revealed multiple order pathways in CPRS that were not linked to the PADR testosterone order template. Testosterone could be ordered in the generic order dialog, medications by drug class, and medications by alphabet, and endocrinology specialty menus without prompting to complete the testosterone order template or redirection to the restricted drug menu (Figure 2). These alternative testosterone ordering pathways were removed in early December 2019 and additional data collection was conducted for 3 months after discontinuation of alternative order pathways, the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period, from December 7, 2019 to February 29, 2020.

Exclusion of Previous Testosterone Prescriptions Predating Chart Review Period, Subgroup Analysis

In the OIG report and the initial retrospective chart review, only veterans without a testosterone prescription in the previous 12 months were evaluated. To assess whether a previous testosterone prescription influenced completion of the PADR and order template, a further subgroup analysis was conducted that excluded veterans who had a previous testosterone prescription at any time before the chart review periods. Therefore, “new testosterone prescription” refers to a veteran who never had a history of being on testosterone vs “former testosterone prescription,” meaning a patient could have had a previous testosterone prescription > 1 year prior to a new VA testosterone prescription.

Results

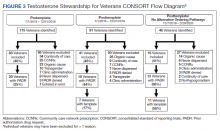

One hundred seventy-five veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the pretemplate period; of these 80 (46%) met eligibility criteria; only 20 eligible veterans (25%) had a completed PADR (Figure 3). Ninety-one veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the posttemplate period of which 41 (46%) veterans were eligible; 18 eligible veterans (44%) had a completed PADR, but only 7 (17%) had a completed testosterone order template.

After excluding veterans who had alternative ordering pathways for testosterone, 46 veterans were identified in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period of which 19 (41%) veterans were eligible. Compared with the posttemplate period, a higher proportion of eligible veterans, 68% (13) had a completed PADR, and 58% (11) had a testosterone order template during the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period.

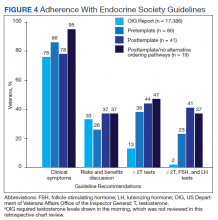

Compared with the OIG report findings, a similar percentage of veterans at VAPSHCS in the pretemplate period had documented clinical symptoms of testosterone deficiency and documented discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy (Figure 4). However, a higher percentage of veterans had biochemical confirmation of testosterone deficiency with ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and evaluation of LH and FSH levels in the pretemplate period (23%) vs that in the OIG report (2%).