This study was undertaken to examine the association between specific sociodemographic variables and aspirin use among a representative sample of Wisconsin adults without CVD, looking both at those for whom aspirin therapy is indicated and those for whom it is not indicated based on national guidelines.

METHODS

Design

We used a cross-sectional design, with data from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW),19 an annual survey of Wisconsin residents ages 21 to 74 years. SHOW uses a 2-stage stratified cluster sampling design to select households, with all age-eligible household members invited to participate. Recruitment for the annual survey consists of general community-wide announcements, as well as an initial letter and up to 6 visits to the randomly selected households to encourage participation.

By the end of 2010, SHOW had 1572 enrollees—about 53% of all eligible invitees. The demographic profile of SHOW enrollees was similar to US census data for all Wisconsin adults during the same time frame.19 All SHOW procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent.

Study sample

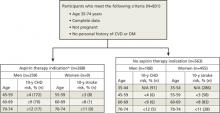

Our analyses were based on data provided by SHOW participants who were screened and enrolled between 2008 and 2010. To be included in our study, participants had to be between the ages of 35 and 74 years; not pregnant, on active military duty, or institutionalized; and have no personal history of CVD (myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, or transient ischemic attack) or CVD risk equivalent (type 1 or type 2 diabetes) at the time of recruitment. Data on key study variables had to be available, as well. (We used 35 years as the lower age limit because of the very low likelihood of CVD in younger individuals.)

|

We stratified the analytical sample (N=831) into 2 groups—participants for whom aspirin therapy was indicated and those for whom it was not indicated—in order to examine aspirin’s appropriate (recommended) and inappropriate use.

Measures

Outcome.

The outcome variable was aspirin use. SHOW had asked participants how often they took aspirin. Similar to the methods used by Sanchez et al,15 we classified those who reported taking aspirin most (≥4) days of the week as regular aspirin users. All others were classified as nonregular aspirin users. Participants were not asked about the daily dose or weekly volume of aspirin.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables considered in our analysis were age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, marital/partner status, employment status, health insurance, and region of residence within Wisconsin.

All participants underwent physical examinations, conducted as part of SHOW, at either a permanent or mobile exam center. Blood pressure was measured after a 5-minute rest period in a seated position, and the average of the last 2 out of 3 consecutive measurements was reported. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated, and blood samples were obtained by venipuncture, processed immediately, and sent to the Marshfield Clinic laboratory for measuring total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Indications for aspirin therapy. We stratified the sample by those who were and those who were not candidates for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention based on the latest guidelines from the USPSTF (FIGURE).10 The Task Force recommends aspirin therapy for men ages 45 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of a coronary heart disease (CHD) event and women ages 55 to 74 years with a moderate or greater 10-year risk of stroke. We used the global CVD risk equation derived from the Framingham Heart Study (based on age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, and total and HDL cholesterol) to calculate each participant’s 10-year risk and, thus, determine whether aspirin therapy was or was not indicated.20 Total and HDL cholesterol values were missing for 94 participants in the analytical sample; their 10-year CVD risk was estimated using BMI, a reasonable alternative to more conventional CVD risk prediction when laboratory values are unavailable.21

FIGURE |

Study (SHOW) sample, stratified based on aspirin indication10 |

*US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines were slightly modified for this analysis: The upper age bound was reduced from 79 to 74 years because the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin did not enroll participants >74 years.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; N/A, not applicable; SHOW, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin.