At 5% to 6%, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is diagnosed in a relatively small proportion of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. However, MCL is important to recognize because of its relatively poorer prognosis and the important role of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) as an adjunct to first-line treatment and, to a lesser extent, in later lines of therapy.

Treatment Options

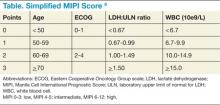

Though pathologic features are beyond the scope of this manuscript, when a definitive diagnosis is made, it is important to differentiate the more aggressive blastoid variant from the more typical pathologic patterns. The indolent form of MCL is diagnosed by clinical presentation as described below. In addition, quantitation of Ki-67 can add prognostic value.1-6 Patients with tumors that express higher levels of Ki-67 have higher relapse rates and shorter overall survivals.2,3,5 The Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) segregates patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups based on the clinical factors of patient age, performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase, and total white blood cell count (WBC) (Table). Use of the MIPI at both initial diagnosis and before first-line autologous HCT can also offer significant prognostic value.1-7 Patients with higher MIPI scores have shorter overall survivals.7,8

For patients who present with indolent clinical features such as a stable leukemic phase, splenomegaly without adenopathy, and low tumor burden, watchful waiting can be utilized. However, approximately 80% of patients will require initial treatment with chemotherapy.1-6

For younger patients and those with good performance status and physiologic reserve, randomized trials have not clearly identified a preferred initial regimen, though initial therapy is typically with the hyperCVAD regimen along with the addition of rituximab.5,9 This regimen is fairly aggressive, requires inpatient hospitalization, is associated with cytopenia and risk of infection, and has not been rigorously proven to be superior in prospective randomized studies, but based on select single-arm studies and retrospective controls, this is commonly used as first-line therapy in the U.S.5,9

Of note, the recent SWOG 1106 U.S. Intergroup study comparing initial therapy with R-hyperCVAD to rituximab+bendamustine was closed early due to poor peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) mobilization in the R-hyperCVAD arm. R-CHOP or R-bendamustine are considered less aggressive alternative regimens for older patients and for those with a poorer overall performance status.

For younger patients, the incorporation of high-dose cytarabine in various combinations during induction has been consistently identified as superior to those regimens without high-dose cytarabine. In general, the comparative studies have rather complex treatment regimens and are not routinely used in the U.S.

Other drugs with proven activity, though currently without a clear therapeutic sequence, include bortezomib, lenalidomide, bendamustine, temsirolimus, and most recently ibrutinib.1-5

Autologous HCT Recommendations

Following initial chemotherapy, autologous HCT is recommended for patients aged < 65 years and with good performance status. Earlier single-arm trials showed that the addition of dose intensification with autologous HCT led to more durable remissions. Both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) support dose intensification with autologous HCT in first remission.

There are no absolute age restrictions for autologous HCT, though patients must have adequate physiologic reserve and good overall performance status. Prognostic physiologic parameters are not as well characterized for autologous HCT as they are for reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation and autologous HCT for multiple myeloma. However, risk indices are being developed for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma undergoing autologous HCT.

While the addition of rituximab has improved the overall response rate of all chemotherapy regimens in patients with MCL, the most convincing survival plateaus still occur with autologous HCT in first remission. Nonetheless, the best first-line therapy has not been proven in prospective randomized fashion.1-6,9-13

Single-arm studies have shown that the R-HyperCVAD regimen can induce complete responses of 58% to 87% of first-line patients.1-3,5 From a practical perspective, for patients receiving R-hyperCVAD and proceeding with autologous HCT, PBSC are typically harvested after the completion of cycle 1B and patients proceed with autologous HCT after cycle 2B.5,9

The best preparative regimen for autologous HCT has not been clearly identified. Options for dose intensification include the more traditional total body irradiation (TBI)-based regimen as well as chemotherapy only, such as the BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) regimen. While there are no comparative studies, a small retrospective analysis suggested benefit for a TBI-based preparative regimen, with a larger and recent European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) review suggesting that the benefit of TBI may be limited to those patients who have not achieved complete remission (CR) before autologous HCT.3

Mantle cell lymphoma is known to be a radiosensitive malignancy, and the use of radioimmunotherapy (RIT) along with HCT has shown promising results in single-arm studies when compared with historical control groups. The current unavailability of radioiodine-based RIT (tositumomab) and the unproven benefit of yttrium-based RIT (ibritumomab tiuxetan) makes this approach still of uncertain benefit. Nonetheless, the suggestion of benefit based on retrospective case control studies suggests that the addition of RIT to autologous HCT for MCL is worthy of further investigation.