According to the CDC, colorectal cancer (CRC) is largely preventable but remains the second leading cancer killer for men and women in the U.S. Screening for polyps (detection of abnormal growths) and surveillance (based on prior bowel preparation quality, findings, and personal and family histories) are key elements for CRC prevention and survival.1 However, inadequate bowel preparation greatly reduces accuracy of its intended purpose: finding and removing precancerous polyps or lesions before they develop into a cancer, typically within a 10-year window. If preparation quality is not satisfactory, the ability of the endoscopist to meet national polyp detection rates is limited. These rates are currently 25% for men and 15% for women.2 Compounding poor preparation, many veterans avoid CRC screening due to anxiety, shame, and fear of what could be found.

Related: Do I Need a Colonoscopy?

About 60% of veterans presenting for colonoscopy have inadequate bowel preparation.3 Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for detection of colorectal pathology and is available to veterans without insurance preauthorization, eliminating a significant barrier to screening.1 Inadequate bowel preparation can result in missed polyps, cancelled procedures, and increased procedure time. Nonadherence to the liquid diet and high-volume, bowel-cleansing solution can lead to a repeated colonoscopy.

Two nurse practitioners (NPs) at the Philadelphia VAMC (PVAMC) gastroenterology (GE) section recognized that many veterans had poor bowel preparation in spite of preprocedure visits, written instructions, and no financial limitations. Repeated colonoscopies were impacting patient satisfaction, facility costs, and endoscopy staff morale. The NPs developed a study to examine bowel preparation outcomes after a group preprocedure class that provided comprehensive and multimedia education in comparison to standard mailed instructions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. The hypothesis was that group patient education would result in better adherence to bowel preparation instructions than did mailed instructions and that better adherence would result in significantly improved colonoscopy outcomes.

Methods

This was a descriptive pilot study with a convenience sample of 200 veterans randomly selected between 2009 and 2011. The study measured 2 groups. The control group received only the mailed standard bowel preparation instructions, whereas the intervention group received the standard bowel preparation instructions and participated in a group intervention class. Eligible participants were aged 45 to 79 years and were enrolled as patients in a single center (PVAMC GE clinic).

Related: E-Consults in Gastroenterology: A Quality Improvement Project

After referral consults were initially selected for appropriate colonoscopy screening or surveillance, potential patient subjects were randomized into either the control or intervention groups by the coin toss method, followed by mailed letters inviting them to participate in the study. If subjects expressed interest, then consent was obtained. The colonoscopy procedure note was updated to reflect bowel preparation quality. All subjects were de-identified. There were about 8 endoscopists; all were board-certified gastroenterologists plus GE fellows who performed procedures at the time of the study. (Fellows rotated every 2 to 4 weeks in the GE clinic and were always accompanied by an attending gastroenterologist.)

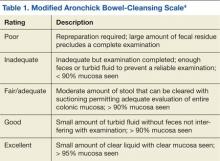

All the endoscopists were instructed in the grading system adapted from the modified Aronchick scale (Table 1).4 This scale measures the quality of bowel preparation for the entire colon: excellent (> 95% visualization of bowel mucosa); good (> 90% of mucosa was visible); fair (some semisolid stool could be suctioned out, but > 90% of mucosa was visible), and poor (semisolid stool cannot be suctioned out and < 90% of mucosa was seen). The modified Aronchick scale also has an inadequate rating, but this was not used in the study. For this study, bowel preparation that was excellent or good received a 1, a fair preparation received a 2, and poor preparation received a 3. The Pearson correlation for the modified Aronchick scale coefficients was 0.62 (P < .001). The value for the kappa statistic was 0.77 (P < .001).5

Results

There were 77 men and 5 women enrolled in the study. The control group had 43 subjects, and the intervention group had 39 subjects. Only 28 subjects each from the control and intervention groups had the quality of bowel preparation rated by the endoscopists. In the control group, 53.6% were rated excellent or good, 42.9% were fair, and 3.5% were poor. In the intervention group, 42.9 % of preparations were excellent or good, 42.8% were fair, and 14.3% were poor (Table 2).

Preparation quality was not described in the procedure documentation for 34.9% and 28.2% of the subjects, respectively, for the control and intervention groups. There was no significant difference in no-show rates to procedures in either of the groups. Based on the data, a Fisher exact test for association was performed (P = .39), indicating there was no evidence of association between the intervention group and preparation quality.