Case Presentation. A 64-year-old US Army veteran with a history of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and fibrinolytic presented with dyspnea to VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS). Seven years prior to the current presentation, at the time of her diagnosis of colorectal cancer, the patient was found to be HIV negative but to have a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test. She was treated with isoniazid (INH) therapy for 9 months. Sputum cultures collected prior to initiation of therapy grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in 1 of 3 samples, with these results reported several months after initiation of therapy. She was a never smoker with no known travel or exposure. At the time of the current presentation, her medications included bupropion, levothyroxine, capsaicin, cyclobenzaprine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Monach, this patient is on a variety of pain medications and has a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. This diagnosis often frustrates doctors and patients alike. Can you tell us about fibromyalgia from the rheumatologist’s perspective and what you think of her current treatment regimen?

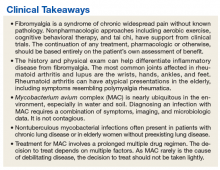

►Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, Chief, Section of Rheumatology, VABHS and Associate Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Fibromyalgia is a syndrome of chronic widespread pain without known pathology in the musculoskeletal system. It is thought to be caused by chronic dysfunction of pain-processing pathways in the central nervous system (CNS). It is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain. It is a common condition, affecting up to 5% of otherwise healthy women. It is particularly common in persons with chronic nonrestorative sleep or posttraumatic stress disorder from a wide range of causes. However, it also is more common in persons with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as lupus, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis. Concern for one of these diseases is the main reason to consider referring a patient for evaluation by a rheumatologist. Often rheumatologists participate in the management of fibromyalgia. A patient should be given appropriate expectations by the referring physician.

Effectiveness of treatment varies widely among patients. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as aerobic exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and tai chi have support from clinical trials, and yoga and aquatherapy also are widely used.1,2 The classes of drugs used are the same as for neuropathic pain: tricyclics, including cyclobenzaprine; serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); and gabapentinoids. In contrast, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are ineffective unless there is a superimposed mechanical or inflammatory cause in the periphery. The key point is that continuation of any treatment should be based entirely on the patient’s own assessment of benefit.

►Dr. Swamy. Seven years later, the patient returned to her primary care provider, reporting increased dyspnea on exertion as well as significant fatigue. She was referred to the pulmonary department and had repeat computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, which indicated persistent right middle lobe (RML) bronchiectasis. She then underwent bronchoscopy with a subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture growing MAC. Dr. Fine, please interpret the baseline and follow-up CT scans and help us understand the significance of the MAC on sputum and BAL cultures.

►Alan Fine, MD, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS and Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Prior to this presentation, the patient had a pleural-based area of fibrosis with possible associated RML bronchiectasis. This appears to be a postinflammatory process without classic features of malignant or metastatic disease. She then had a sputum, which grew MAC in only 1 of 3 samples and in liquid media only. Importantly, the sputum was not smear positive. All of this suggests a low organism burden. One possibility is that this could reflect colonization with MAC; it is not uncommon for patients with underlying chronic changes in their lung to grow MAC, and it is often difficult to tell whether it is indicative of active disease. Structural lung disease, such as bronchiectasis, predisposes a patient to MAC, but chronic MAC also may cause bronchiectasis. This chicken-and-egg scenario comes up frequently. She may have a MAC infection, but as she is HIV negative and asymptomatic, there is no urgent indication to treat, especially as the burden of therapy is not insignificant.

►Dr. Swamy. Do we need to worry about Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)?

►Dr. Fine. Although she was previously PPD positive, she had already completed 1 year of isoniazid (INH) therapy, making active MTB less likely. From an infection control standpoint, it is important to distinguish MAC from MTB. The former is not contagious, and there is no need for airborne isolation.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Fine, where does MAC come from? Does it commonly cause disease?

►Dr. Fine. In the environment, MAC is nearly ubiquitous , especially in water and soil. In one study, 20% of showerheads were positive for MAC; when patients are infected, we may suggest changing/bleaching the showerhead, but there are no definitive recommendations.3 Because MAC is so common in the environment, it is unlikely that measures to target MAC colonization will be clinically meaningful. On the other hand, the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections is increasing across the US, and it may be a common and frequently underdiagnosed cause of chronic cough, especially in postmenopausal women.

►Dr. Swamy. Four years prior to the current presentation, the patient developed a cough after an upper respiratory tract infection that persisted for more than 2 weeks. Given her history, she underwent a repeat chest CT, which noted a slight increase in nodularity and ground-glass opacity restricted to the RML. She also reported dyspnea on exertion and was referred to the pulmonary medicine department. By the time she arrived, her dyspnea had largely resolved, but she reported persistent fatigue without other systemic symptoms, such as fevers or chills. Dr. Fine, does MAC explain this patient’s dyspnea?

►Dr. Fine. As her pulmonary symptoms resolved in a short period of time with only azithromycin, it is very unlikely that her symptoms were related to her prior disease. The MAC infection is not likely to cause dyspnea on exertion and fatigue and should be worked up more broadly before attributing it to MAC. In view of this, it would not be unreasonable to follow her clinically and see her again in 6 to 8 weeks. In this context, we also should consider the untoward impact of repeated radiation exposure derived from multiple CT scans. When a patient has an abnormality on CT scan, it often leads to further scans even if the symptoms do not match the previous findings, as in this case.

►Dr. Swamy. Given her ongoing fatigue and systemic symptoms (morning stiffness of the shoulders, legs, and thighs, and leg cramps), she was referred to the rheumatology department where the physical examination revealed muscle tenderness in her proximal arms and legs with normal strength, tender points at the elbows and medial side of the bilateral knees, significant tenderness of lower legs, and no synovitis.