Key components of the IBD medical home

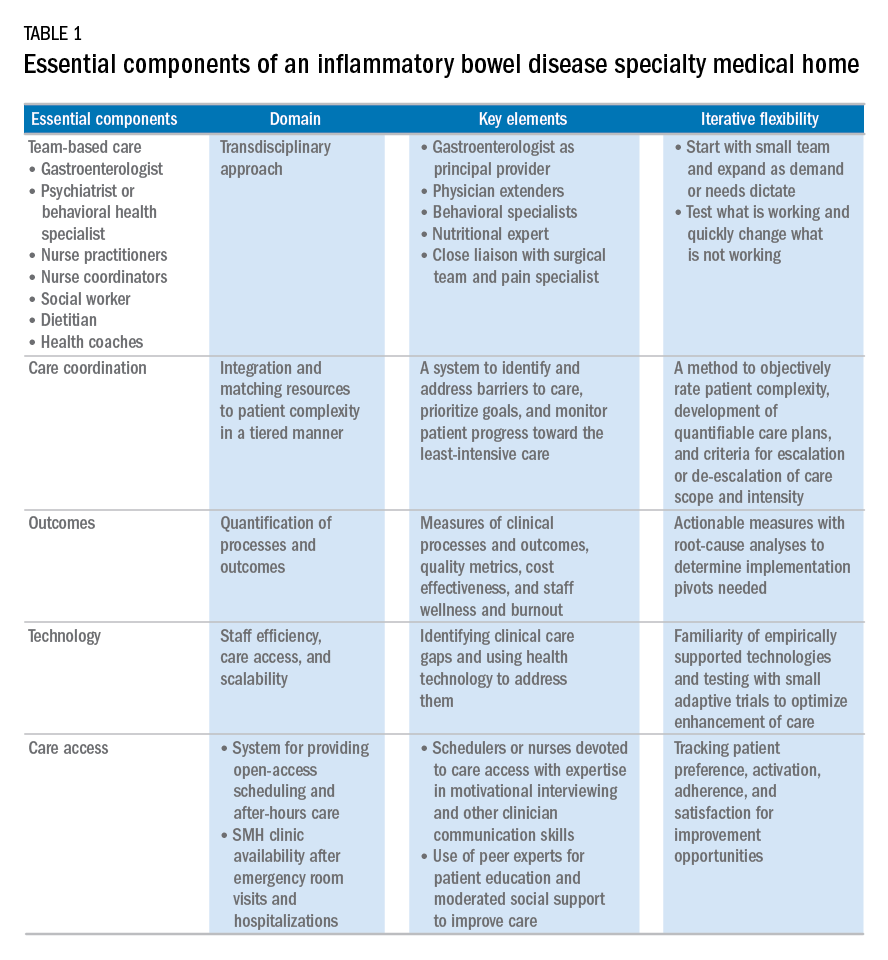

Based on our experience, we believe the following are key components of a successful IBD SMH: 1) team-based care with physician extenders, nurse coordinators, schedulers, social workers, and dietitians as essential members of the IBD SMH; 2) effective care coordination to reduce barriers to comprehensive biopsychosocial care; 3) tracking of process and outcome metrics of interest; 4) appropriate use of technology to enhance clinical care; and 5) care access (e.g., open-access appointments), after-hours care, and follow-up care after emergency room visits and hospitalizations (Table 1).

There is not a one-size-fits-all SMH model given the range of different subspecialty practices. The appropriate dose for each specific setting may vary, and we recommend an iterative deployment process starting with a few case studies and then sequentially rolling out to a larger-scale clinical sample. The goal of the initial SMH is to show feasibility and understand which components are most critical for successful implementation.Although the eventual goal of an IBD SMH is to consolidate health care for all IBD patients, the initial launch stages are more likely to succeed if the SMH focuses on the subgroup of IBD patients who use health care excessively, often in an unplanned fashion (e.g., emergency department visits or hospitalizations). In conjunction with a payer, it is easy to identify the most costly IBD patients in a cohort. For example, for initial enrollment, the UPMC IBD SMH selected patients between the ages of 18 and 55 years, with confirmed Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and evidence that IBD was a primary driver of patients’ health care utilization; the latter was defined if the majority of health care expenditures in the prior year was related to IBD (as judged by International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th revisions, primary and secondary diagnoses).

Team-based care

A central component to our IBD SMH was the creation of an integrated team. Supplementary Table 2 (at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026) describes various positions that are vital for a successful SMH. For a team approach to be most effective, there needs to be clear definitions or roles and role overlaps so that team members can work as a cohesive, organized, and efficient unit. Physician extenders are critical to the model’s success and are trained to make routine IBD care decisions, provide basic primary care, and coordinate care with the gastroenterologist to meet patient needs. The staff-to-patient ratio requirements may vary from region to region and from SMH to SMH. The nurse coordinators and physician extenders assume the burden of day-to-day patient care, and are supervised by the gastroenterologist and psychiatrist. In our UPMC IBD SMH, the ratio of one nurse coordinator and one certified nurse practitioner per 500 patients is sufficient. In addition, one social worker, one dietitian, one scheduler, one gastroenterologist, and one psychiatrist per 1,000 patients is our current model. To date, we have enrolled more than 500 patients, and through funding from our UPMC HP, we have just hired our second nurse coordinator and second nurse practitioner in anticipation of 1,000 patients by year 4.

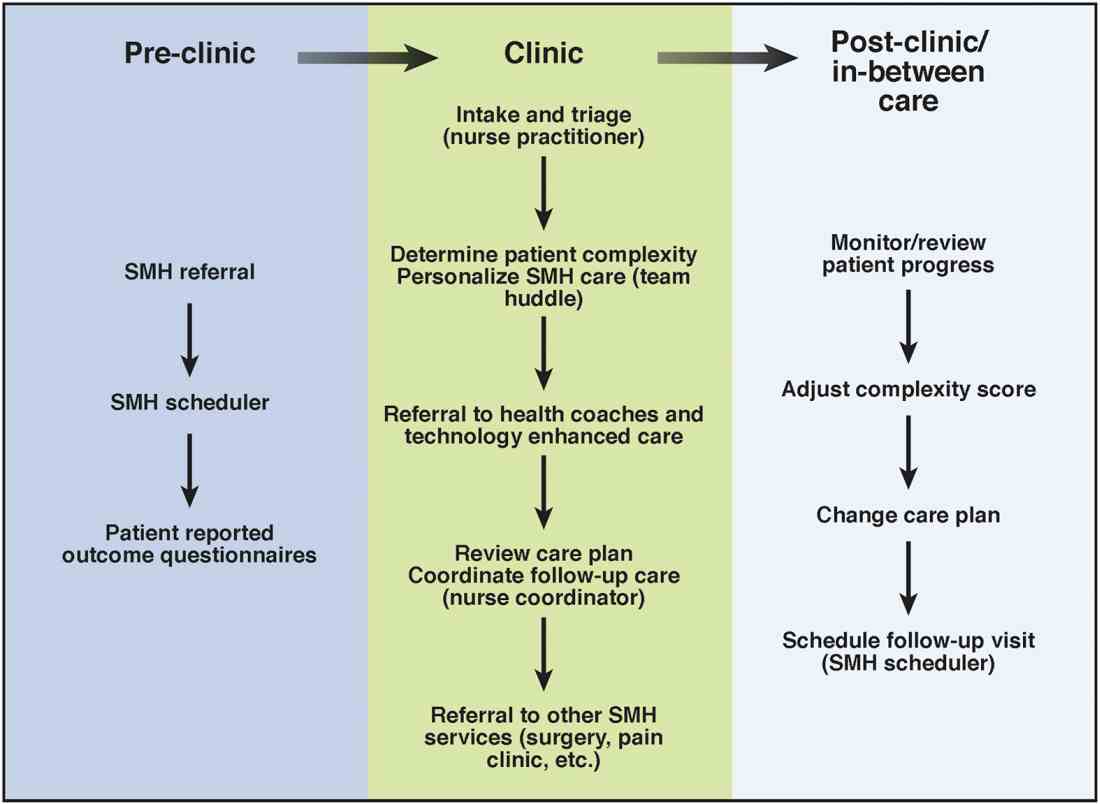

In an ideal team model, all staff, both behavioral and medical, are trained in basic behavioral assessment and interventions, motivational interviewing, and disease self-management techniques so that the behavioral health specialist can be considered a second-line provider or a consultant to the gastroenterologist for the most complex psychiatric patients. Figure 1 shows a typical patient’s trajectory through the IBD SMH.Care coordination and incorporation of technology

The team composition is organized to provide tiered care for optimal efficiency. For such a stepped care model to be effective and scalable, two components are essential. The first component is a care coordination system that allows for the reliable classification of the biological, psychological, social, and health systems barriers faced by patients. To this end, our SMH developed an IBD-specific complexity grid (Supplementary Table 3; at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.026) that was derived from a primary care model.12 The second component is the use of technology-enhanced care to scale delivery of services in a population health model. Examples of technology in our SMH include the use of telemedicine/telepsychiatry by secure video, health coach virtual visits, remote monitoring, and provider-assisted behavioral interventions that patients can access on their smart phones.

New payment models for specialty medical homes

The SMH transitions away from relative value unit–based reimbursement and toward a value-based paradigm. In the SMH, the gastroenterologist serves as the principal medical provider for the IBD patient. Both providers and payers will be able to refer patients to the SMH. Data on quality metrics will be tracked and physician extenders and nurse coordinators will help ensure that goals are met. Quality improvement, preventive medicine, telemedicine, and point-of-contact mental health care will replace the volume-based relative value unit system.