For gastroenterologists who enter academic medicine, the most common career track is that of clinician educator (CE). Although most academic gastroenterologists are CEs, their career paths vary substantially, and expectations for promotion can be much less explicit compared with those of physician scientists. This delineation of different pathways in academic gastroenterology starts as early as the fellowship application process, before the implications are understood. Furthermore, many community gastroenterologists have appointments within academic medical centers, which typically fall into the realm of CEs.

A review of all gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program websites listed on the American Gastroenterological Association website showed that 33 of 175 (18.8%) programs endorse distinctly different tracks, usually distinguishing traditional research (i.e., basic science, epidemiology, or outcomes) from clinical care of patients (i.e., clinician educator or clinical scholar). One of the most common words appearing in descriptions of both tracks was “clinical,” highlighting that a good clinician educator or researcher is, first and foremost, a good clinician.

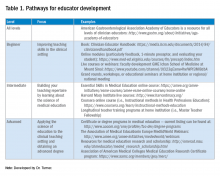

With clinical duties requiring the majority of a CE’s time and efforts, a reasonable assumption is that CEs are clinicians who teach trainees via lectures, clinic, endoscopy, and/or inpatient rounds. Although such educational endeavors form the backbone of a CE’s scholarly activities, what constitutes scholarship for CEs is much more diverse than many people realize. The variability in what a career as a CE may look like can be both an obstacle and an opportunity. Included in the category of CE are community clinicians who have a stake in the education of residents and fellows and play an important role in trainee learning. Sherbino et al1 defined a CE as “a clinician active in health professional practice who applies theory to education practice, engages in education scholarship, and serves as a consultant to other health professionals on education issues.”

Because we recognize that many community and academic gastroenterologists spend the majority of their education efforts teaching trainees, we have made every effort to ensure that the five recommendations listed later are equally pertinent to all gastroenterologists who devote any portion of their careers to educating trainees, colleagues, allied health professionals, as well as patients. For example, a CE who primarily teaches trainees still can benefit from learning how to better document their efforts, receive mentorship as an educator, take everyday activities and convert them into scholarship, share teaching materials with broader audiences, and learn new teaching techniques without ever opening a book on education theory. For community-based physicians, this can assist in obtaining recognition from the academic centers for their teaching efforts. We hope that the five recommendations that follow will serve to guide those just setting out on the CE path, as well as for those who have trodden it for some time.