Position of equipment

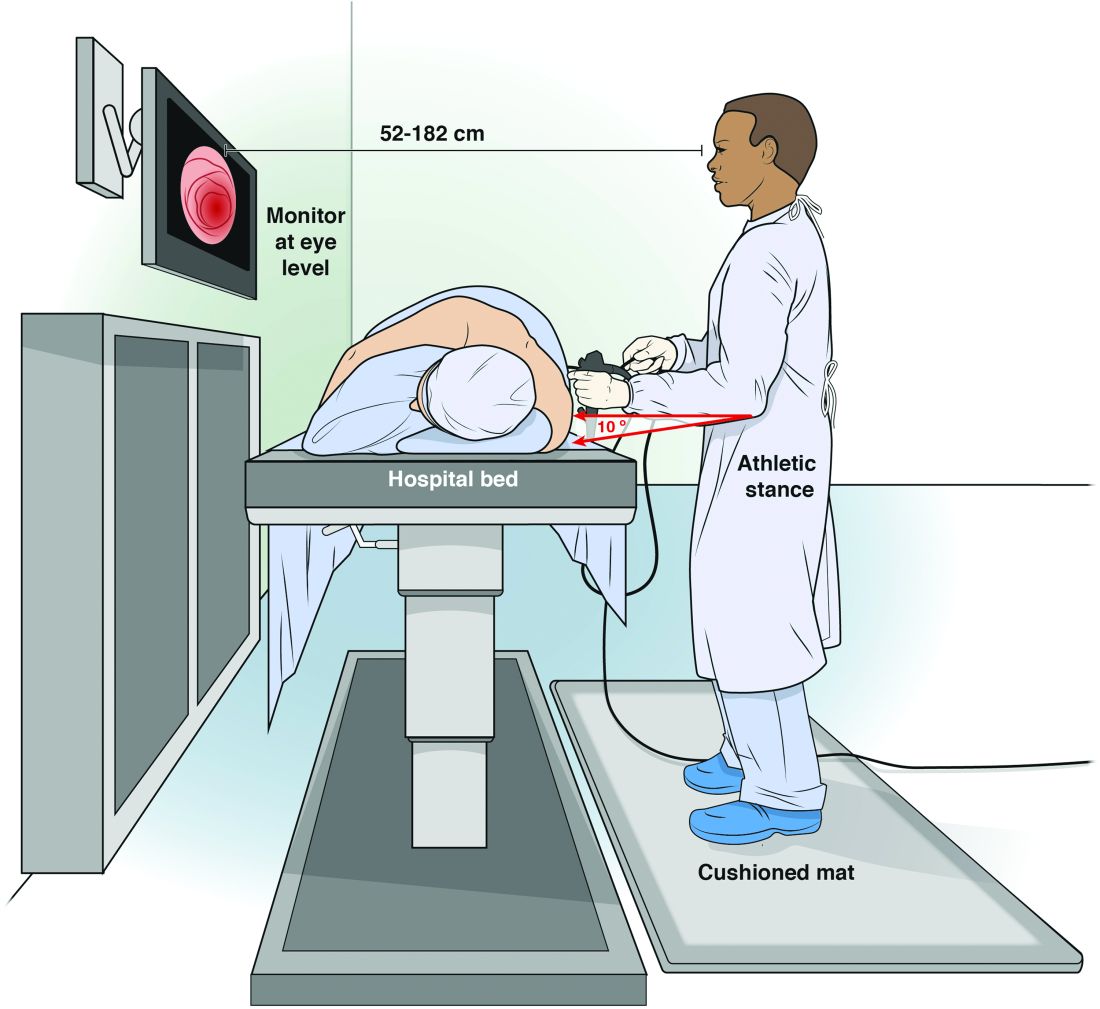

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.