GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or nonprocedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk.

Informed consent

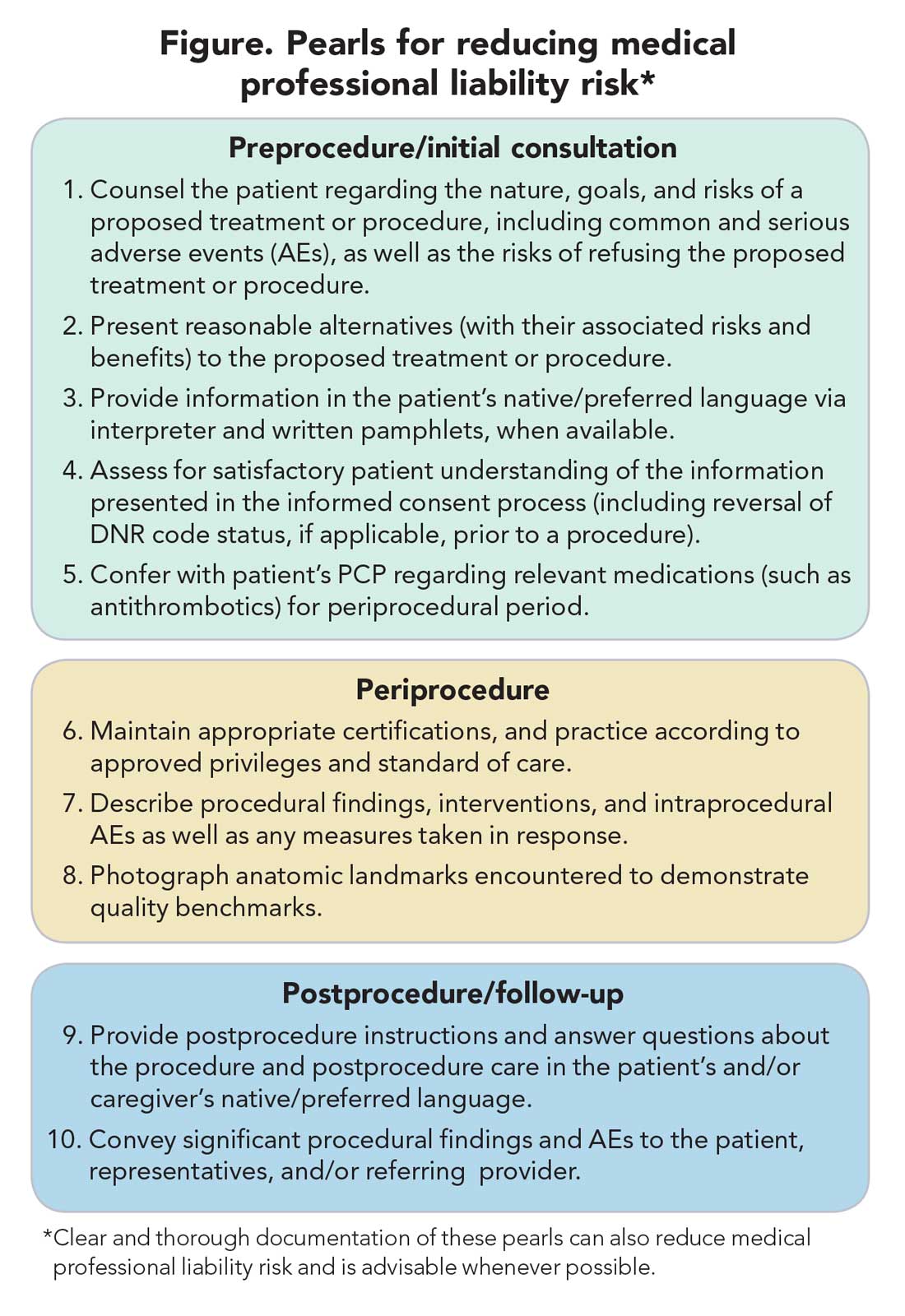

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal.5,13,14 While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., assuming an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure that the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, there is a discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, reasonable alternatives are presented, the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives are discussed, and the patient’s comprehension of these things is assessed (Figure).15 Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (Figure).16

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% involve endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% involve esophagogastroduodenoscopy.8 Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with esophagogastroduodenoscopy, is subject to rare but serious AEs.18,19 Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (such as severe colonic inflammation or coagulopathy) and, as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of postprocedural development of signs/symptoms (such as tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, or hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (such as blood work and imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe.19

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure.11 Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that most of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (for example, that it was performed based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology), or was for diagnostic purposes (for example, being done instead of noninvasive imaging) rather than therapeutic.20-23 This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (for example, needing a surrogate decision-maker’s consent or representing medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1%-1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part because of the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement.24,25 Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thereby prompting (possibly unfounded) perceptions of causality.24-27 Therefore, such scenarios merit unique additional preprocedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if there’s no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss both the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful.27

Antithrombotic agents

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics, including anticoagulants and antiplatelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist.28 For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for antithrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the antithrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered according to recommendations.28,29 While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal periprocedural management of antithrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing antithrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) the antithrombotic therapy should be held (Figure). This shared decision-making, which should also include the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

Provider defense mechanisms

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk.30,31

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (such as medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated.2,30,31 Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that more than 50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications, and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications.30,32 While assurance behaviors may seem likely to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk, as well as health care expenditures.3,30,32

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (for example, the actual procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient.30,31 Two clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior include the following: An advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP might refer a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), or a gastroenterologist might refer a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection themselves. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences.33 For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up.2,30,31 This may be viewed as noncompliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thereby increasing MPL risk.

Documentation tenets

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence.16 Documenting, for instance, preprocedure discussion of potential risk of AEs (such as bleeding or perforation) or procedural failure (for example, missed lesions)can protect gastroenterologists (Figure).16 While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which itself reduces MPL risk), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation that indicates that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (Figure).16,34 In this context, it is worth recalling the adage: “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Curbside consults versus consultation

Also germane here is the topic of whether documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (such as anything that could also be answered by searching the Internet or reference materials) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (for example, when patient identifiers have been shared or their EHR has been accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation – even if seemingly trivial – should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, and such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL.16,35 These considerations arise not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing postprocedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when one is communicating with non–English speakers and is not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship.36 Additionally, written materials (such as consent forms, procedural information) in patients’ native/preferred languages should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (Figure).35

Challenges posed by telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make health care more accessible, it does not lessen the clinicians’ duty to patients and may actually expose them to greater MPL risk.18,37,38 Therefore, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters.18,37,38 Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim.18,37,38

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (such as when a telemedicine visit was substituted for an in-person clinic encounter), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely preprocedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies as needed to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

Vicarious liability

“Vicarious liability” is defined as that extending to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted.39 Therefore, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (such as fellow trainees and non–physician practitioners).39 Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that, if failure occurs, harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model.”40