Dear colleagues and friends,

The Perspectives series continues! There are few issues in our discipline that are as challenging, and controversial, as liver transplant prioritization. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) has been the mainstay for organ allocation for nearly 2 decades, and there has been vigorous debate as to whether it should remain so. In this issue, Dr. Jasmohan Bajaj and Dr. Julie Heimbach discuss the strengths and limitations of MELD and provide a vision of upcoming developments. As always, I welcome your feedback and suggestions for future topics at ginews@gastro.org.

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Yes, it’s time for an update

BY JASMOHAN S. BAJAJ, MD, AGAF

Since February 2002, the U.S.-based liver transplant system has adopted the MELD score for transplant priority. Initially developed to predict outcomes after transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt, it was modified to exclude etiology for the purpose of listing patients.1

There were several advantages with MELD including objectivity, ease of calculation using a website, and over time, a burgeoning experience nationwide that extended even beyond transplant. Moreover, it focused on “sickest-first,” did away with the extremely “manipulable” waiting list, and left off hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and ascites severity.1 However, even earlier on, there were concerns regarding not capturing hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and some complications of cirrhosis that required exceptions. The points awarded to all these exceptions also changed with time, with lower priority and reincorporation of the waiting list time for HCC. Over time, the addition of serum sodium led it to be converted to “MELD-Na,” which now remains the primary method for transplant listing priority.

But the population with cirrhosis that existed 20 years ago has shifted radically. Patients with cirrhosis currently tend to either be much older with more comorbid conditions that predispose them to chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular compromise or be younger with an earlier presentation of alcohol-associated hepatitis. Moreover, the widespread availability of hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication has changed the landscape and stopped the progression of cirrhosis organically by virtually removing that etiology. This is relevant because a recent United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) analysis showed that the concordance between MELD score and 90-day mortality was the lowest in the rapidly increasing population with alcohol-related and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease etiologies, but conversely, this concordance was the highest in the population with hepatitis C–related cirrhosis.2 These demographic shifts in age and changes in etiology likely lessen the predictive power of the current MELD score iteration.

There is also increasing evidence that MELD is “stuck in the middle.” This means that both patients at low MELD score and those with organ failures may be underserved with respect to transplant listing with the current MELD score iteration.

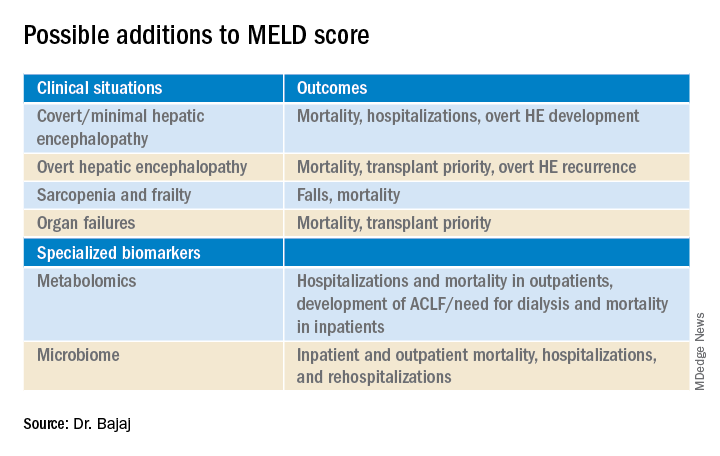

Among patients with a MELD score disproportionately lower than their complications of cirrhosis several studies demonstrate the improvement in prognostication with addition of covert HE, history of overt HE, frailty, and sarcopenia indices. These are independently prognostic variables that affect daily function, affect patient-reported outcomes, and can influence readmissions. The burden of impending falls, readmissions, infections, and overall ill health is not captured even though relatively objective methods such as cognitive tests and documented admissions for overt HE can be utilized.3 This relative mistrust in including HE and covariables likely harkens back to a dramatic reduction in grade III/IV HE severity seen the year after MELD introduction, when compared with the year before, during which that designation was added to the listing priority.4 However, objective additions to the MELD score that capture the distress of patients and their families with multiple readmissions for HE worsened by sarcopenia are desperately needed (see table).

On the other extreme, there is an increasing recognition of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and higher acceptability for transplanting alcohol-associated hepatitis (AAH).5 Prognostic variables in AAH have relied on Maddrey’s score and MELD score as well as the dynamic Lille score. The ability of MELD to predict outcomes is variable, but it is still required for listing these critical patients. A relatively newer entity, ACLF is defined variably across the world. In retrospective studies of the UNOS database in which patients were listed based on native MELD score rather than ACLF grades, there was a cut-off beyond which transplant was not useful. However, there is evidence that organ failures that do not involve creatinine or INR can influence survival independent of the MELD score.5 The rapidly increasing burden of critical illness may force a rethink of allocation policies, but a recent survey among U.S.-based transplant providers found little appetite to do so currently.

Objectivity is a major strength of the MELD score, but several systemic issues, including creatinine variability by sex, interlaboratory inconsistencies in laboratory results, and lack of accounting for international normalized ratio (INR) changes in those on warfarin or other INR-prolonging medications, to name a few that still exist.6 However, in our zeal to list patients and get the maximum chance for organ offers, there is a tendency to maximize or inflate the listing scores. This hope to provide the best care for patients under our specific care could come at the expense of patients listed elsewhere, but no score, however objective, is going to completely eliminate this possibility.

So, does this mean MELD-Na should be abandoned?

Absolutely not. An ecosystem of practitioners has now grown up under this system in the U.S., and it is rapidly being exported to other parts of the world. As with everything else, we need to keep up with the times, and for the popular MELD score, it needs to be responsive to issues at both extremes of cirrhosis severity. Studies on specialized markers such as serum, urine, and stool metabolomics as well as microbiome could be an objective addition to MELD score, but further studies are needed. It is also likely that artificial intelligence approaches could be used to not only improve access but also geographic equity that has plagued liver transplant in the U.S.

In the immortal words of Bob Dylan, “The times, they are a-changin’ …” We have to make sure the MELD score does too.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is with the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and Richmond VA Medical Center. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kamath PS and Kim WR. Hepatology. 2007;45:797-805.

2. Godfrey EL et al. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:3299-307.

3. Acharya C and Bajaj JS. Liver Transpl. 2021 May 21. doi:10.1002/lt.26099.

4. Bajaj JS and Saeian K. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:753-6.

5. Artru F and Samuel D. JHEP Rep 2019 May;1(1):53-65.

6. Bernardi M et al. J Hepatol 2010 Dec 9;54:1297-306.