News

Dr. Kalaycio: My name is Matt Kalaycio and I'm the Chairman of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at the Cleveland Clinic. Today I’m joined by Drs. Mike Deininger, Division Chief of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute and Michael Mauro, Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Program Director at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York – together we will discuss practical issues surrounding CML diagnosis, management and treatment options including TKIs and investigational therapies.

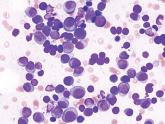

Dr. Kalaycio: Often, the patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) gets admitted to the hospital, or an emergency consult is called, because the white count is up for a concern of leukemia. The treatment team sees the differential circulating blasts, and they worry about acute leukemia. Then the hematologist comes and needs to make a decision about whether or not to do a bone marrow biopsy.

When the patient presents in such a manner, I often see that bone marrow biopsies are not performed. I would like to start by asking where you both stand with regard to the necessity of a bone marrow biopsy at the time of diagnosis. I'll start with Dr. Deininger.

Dr. Deininger: I would strongly be in favor of a diagnostic biopsy as well as a smear. The reason is that I think this is the one and only chance to get a clear disease classification into chronic phase, accelerated phase, and blast crisis.

The third may be rare. There are occasional patients who have sheets of blasts who would not be seen on just a differential. For these patients, of course, the treatment decisions are going to be very different compared to a patient in chronic phase.

I think this is an opportunity that shouldn't be missed and I would always recommend that.

Dr. Kalaycio: Dr. Mauro.

Dr. Mauro: I couldn't concur more. With so much focus on the change in disease status from presentation to early response, I think understanding the scope of the disease at diagnosis, including the bone marrow, is essential and either revealing or reassuring. Although we focus mostly on early molecular response, when expectations go awry, not having as full a picture of the disease prior to treatment leaves you less informed about best treatment.

Making sense of accelerated phase features is a good example; the difference in outcomes between chronic phase patients and those who have morphologic features of accelerated phase—with or without cytogenetic features (clonal evolution)—compared with those with clonal evolution can only drive initial and long term treatment decisions. Without cytogenetics and morphology together, such key pieces of the puzzle are missing; it is worth it for the practitioner and patient to have all the data in hand at all times.

Dr. Kalaycio: Once the diagnosis has been made and the biopsy was not done and now you're seeing the patient having either been on hydroxyurea for a month or having had tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) for a month, do you bother with the bone marrow biopsy at that point?

Dr. Deininger: Well, that is a very good question. I think we would probably still do it most of the time. I think it's very clear that the information you can gather from that is less valuable. I think one should try to make up for the omissions as much as possible. We would still go for it.

Dr. Kalaycio: Interesting. The other thing that happens a lot is a patient will be started on hydrea while you're waiting for BCR-ABL to return either by fluorescence in situ hybridization or quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

I wonder if you have your own set of internal guidelines for when hydroxyurea should be employed or not.

Dr. Mauro: If you look back at some of the original imatinib trials—the phase I trials—patients initiated TKI with higher blood counts, a median around 25,000 and up to 200,000, and responded with excellent tolerance.1 I think there's a bit of overapplication of hydroxyurea early in CML, prior to initiation of TKI, which often confounds and complicates the early myelosuppressive toxicity of TKIs. With use of more potent TKIs, there may be greater amounts of myelosuppression as the leukemic clone may clear faster.

I think we may get ourselves into a bit of a bind by overusing hydroxyurea and then needing to hold and lower TKI dosages quickly when that may not have been necessary had we simply deployed the TKI sooner.

My general rule would be to use hydroxyurea for symptoms if necessary or for more extreme counts where leukostasis is a concern. – Michael Mauro, MDMy general rule would be to use hydroxyurea for symptoms if necessary or for more extreme counts where leukostasis is a concern. The other question that often comes up is about tumor lysis and hydration, and how closely these need to be managed. The likelihood of tumor lysis is low in CML treated with TKIs, but more frequent early labs and good hydration are always the right thing to do; better safe than sorry!

Dr. Deininger: I second what Michael just said. To your question about whether we have an algorithm, I have to admit we don't. I think it's up to the discretion of the treating physician to initiate hydroxyurea or not.

Dr. Kalaycio: Sure. When you start hydroxyurea, do you routinely add allopurinol?

Dr. Deininger: We tend to do that. I know that some people think it's unnecessary. It's such a low-risk and low-cost intervention that I think that it's hard to get anything wrong here.

Dr. Mauro: Right, we tend to do the same. Whether we need to or not is a different question, I suppose.

Dr. Kalaycio: One more thing about the initial presentation and assessment of a patient with what you think might be a myeloproliferative disorder, CML, how important do you find it, Dr. Mauro, to measure splenomegaly and calculate a risk score?

Dr. Mauro: I think it's very useful information. The spleen size factors heavily into the risk score and the risk score does forecast response to a degree. We've looked at calculation of risk score in recent large observational studies and it is under-reported and underutilized. It winds up being useful for two reasons. One, it does set expectations for response, and US treatment guidelines (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] guidelines) note that treatment choice may be different for low versus high risk Sokal score.2

I think the second and most intriguing reason to assess Sokal risk seems now to be the impact that risk score has on the ability to proceed to a treatment-free remission (TFR). There appear to be differences in outcomes in patients with high-risk versus low-risk disease despite both having what is required to proceed to TFR in trials, namely consistent and deep molecular remission over a number of years.

Given these implications, we really ought to be gathering the initial risk stratification and quantifying spleen size. It's an important part of our initial assessment.

Dr. Kalaycio: Dr. Deininger?

Dr. Deininger: I think there's a lot of agreement today. I absolutely think that measuring the spleen size ascertains that you've got all these diagnostic parameters available. I think that should be part of the initial evaluation and work-up and will allow some prognostication.