There are plenty of leadership books, seminars, podcasts, and websites available for the aspiring physician leader. However, not all of them are pertinent to the health care environment. As chairman of a large academic department, I have sifted through some of these resources and have found a few that have been particularly helpful to me. One of the more useful is the drama triangle.

Here’s an example: Pat, the administrator, just sent Sam an email stating that, starting today, all computers will be automatically turned off at 5 p.m. and cannot be restarted until 8 a.m. the next day. The reasons are many but unimportant to Sam because they pale in comparison to the inconvenience this places on Sam’s ability to finish work in the evening. No one asked about this change or even gave advance warning.

Sam’s initial reaction to such an announcement is one of denial. This must be a joke. Are you kidding me? What kind of an idiot would dream this up? When Sam asks around the office for clarity, the response is not reassuring. Yes, the computers are being turned off for less than compelling reasons. Unwelcome change has just intruded on Sam’s otherwise comfortable personal environment.Anger builds in Sam, especially toward Pat. Something has to be done about this! That something becomes a petition to Kelly, a supervisor/manager/director/chairman with authority. Sam recounts the surprise of the order, details the inefficiencies created, expresses indignation at not being consulted first, lists the personal failings of Pat, and demands an immediate resolution to the problem. Kelly wants to help Sam and approaches Pat to reverse the order. Kelly feels good about helping Sam, and Sam feels great about going to Kelly. Pat doesn’t feel good at all.

Sam started, and Kelly completed, the drama triangle.

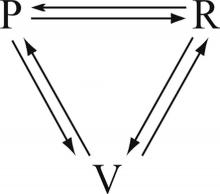

Stephen Karpman, MD first described the drama triangle in 1968. (Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin. 7[26]:39-43. https://www.karpmandramatriangle.com/), and it has evolved since. Broadly, the three corners of the triangle consist of the aggrieved Victim (Sam), the enabling Rescuer (Kelly), and the unsuspecting Persecutor (Pat). The rescuer means well and only wants to help the victim. As interlocutor on behalf of the victim, though, the triangle becomes complete and difficult to break apart, creating increasing tension over time between the persecutor and the victim often resulting in one or the other resigning their position. Once aware that such triangles commonly exist, recognizing them becomes as easy as creating them.Breaking a drama triangle requires uncomfortable work building trust and a more functional relationship between the three players. Ideally, the victim becomes challenged, not threatened. The rescuer becomes a coach, not an enabler. The persecutor raises the bar rather than creating obstacles. With roles redefined, trust is restored. There are many methods and techniques to develop psychological safety and interdependent trust, but the work is the critical first step toward improving the function of a team (Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. Jossey-Bass).

What could Kelly have done to stop a triangle from forming? Sam wanted help, and Kelly’s first instinct is to do just that. However, by completing the triangle with a visit to Pat, Kelly creates more tension between Pat and Sam. To help both Sam and Pat, Kelly has to resist the temptation to rescue Sam from Pat and instead leverage Sam’s trust to begin asking Sam questions that lead Sam toward resolution of Sam’s own problem.

Aware of drama triangles, Kelly asks Sam what the ideal situation would be. Sam replies that all the work would get done by the end of the day. Kelly then asks what the current situation is. According to Pat, the computers turn off at 5, but the work is not done by then. Then, Kelly asks Sam what could be done before 5 that would help get the work done. Sam considers the question and then begins to list some changes to work flow that could allow greater efficiency during the day. Sam also decides to meet with Pat to explain how the two of them can improve communication in the future. Through coaching, Kelly defuses Sam’s anger, avoids a drama triangle, and gets Sam to start considering previously unknown solutions. The model Kelly uses to begin the work of breaking the triangle is sometimes called structural, or dynamic, tension.

Drama triangles compromise trust. The workplace culture can either enable simmering tensions and resentments to persist or it can foster psychological safety that allows for open and honest debate whereby all are heard and validated when change inevitably occurs. Exploring structural tension can build a sense of team and restore trust. A more robust discussion of structural tension will have to wait until my next column. In the meantime, as yourselves, Where do you see drama triangles? What worked to break them? What failed?

For more reading: Emerald, D. (2010). The Power of Ted* (The Empowerment Dynamic). Bainbridge Island, WA: Polaris Publishing.

I invite you to reply to hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com to initiate a broader discussion of physician leadership. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com. Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.