Medical fitness to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy is assessed by a number of factors and varies by institution, but most frequently consider functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status or Karnofsky Performance Status), creatinine clearance, hearing preservation, peripheral neuropathy, and cardiac function.24 Many programs will elect to defer cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with low performance status (ie, < 60–70 on Karnofsky scale or > 2 on ECOG scale), creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min, or significant heart failure (NHYA class III or worse). Cisplatin-based chemotherapy may worsen hearing loss in those with hearing loss of 25 dB from baseline at 2 continuous frequencies and also may worsen neuropathy in those with baseline grade 1 peripheral neuropathy. However, these adverse outcomes must be balanced against the curative intent of the multimodality systemic approach.

In patients with renal insufficiency, caution must be taken with regard to cisplatin. Percutaneous nephrostomy placement or ureteral stenting should be attempted to relieve any ureteral outlet obstruction and restore kidney function if a patient’s renal insufficiency has resulted from this obstruction. If medical renal disease or long-term renal insufficiency is present, however, patients should instead be referred for immediate cystectomy or for a bladder-preserving approach. Generally, a creatinine clearance of 60 mL/min is required to safely receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy, although some advocate for treatment with a creatinine clearance as low as 50 mL/min. When this extended criterion is used, the dose of cisplatin may be split over 2 days to minimize renal toxicity and maximize hydration. Analysis of renal function utilizing a 24-hour urine collection should be incorporated whenever possible, as estimates of creatinine clearance have been demonstrated to be inaccurate in some instances.25

For cisplatin-eligible patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a cisplatin base has consistently demonstrated a survival benefit when given prior to surgery.26,27 Historically, several different platinum-based regimens have been studied, with none showing superior effectiveness in a randomized trial over the others in the neoadjuvant setting. These regimens have included classic MVAC, dose-dense MVAC (MVAC with pegfilgrastim), GC (gemcitabine and cisplatin), and CMV (methotrexate, vinblastine, cisplatin, and leucovorin).

While classic MVAC was preferred in the 1990s and early 2000s,28,29 the availability of growth factor, such as pegfilgrastim, has made dose-dense MVAC (otherwise referred to as accelerated MVAC or ddMVAC) widely preferred and universally recommended over classic MVAC. The ddMVAC regimen with the addition of a synthetic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is substantially better tolerated than classic MVAC, as the G-CSF support minimizes the severe toxicities of classic MVAC, such as myelosuppression and mucositis, and allows for the administration of drugs in a dose-dense fashion.30,31

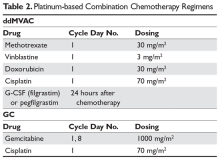

Both ddMVAC and GC are considered reasonable options for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and are the predominant choices for cisplatin-eligible patients (Table 2).

CMV is seldom used, largely because it has not shown superior survival when compared with cisplatin alone.32 ddMVAC with G-CSF is typically given for 3 or 4 cycles prior to surgery; this regimen consists of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin on day 1, and pegylated G-CSF 24 hours after the last chemotherapy dose. Each cycle can be completed in 14 days, which is half the time of classic MVAC, with significantly fewer adverse effects. Regardless of response to neoadjuvant therapy, radical cystectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed after completion of neoadjuvant therapy in muscle-invasive disease. Patients who have a complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a superior long-term prognosis compared with those who have residual disease, suggesting that a subset of patients may actually be cured by chemotherapy alone.33 Certain genomic markers have shown promise in predicting those most likely to benefit from neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy, and ongoing studies are exploring whether patients who harbor certain mutations may safely forgo cystectomy.34,35Prospective data defining the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients after cystectomy has been fraught by a variety of factors, including the known benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the high complication rate of cystectomy making chemotherapy infeasible, and clinician bias that has hampered accrual in prior trials. Thus, no level 1 evidence exists defining the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy. In a report of the largest study performed in this setting, there was a statistically significant benefit in PFS but not in OS.36 Criticisms of this trial include its lack of statistical power due to a failure to accrue the targeted goal and the preponderance of node-positive patients. Regardless, for patients who have pT2–4, N1 disease after radical cystectomy and remain cisplatin-eligible after not receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, this remains an option.

Despite the established clinical dogma surrounding neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, some patients are either not eligible for or decline to receive radical cystectomy, while others are not candidates for neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy for the reasons outlined above. For patients who are surgical candidates but unable to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy due to renal or cardiac function, they may proceed directly to surgery. For patients unable or unwilling to proceed to radical cystectomy regardless, bladder preservation strategies exist. Maximal TURBT may be an option for some patients, but, as outlined above, used alone this would be likely to lead to a high degree of local and distant failure. Combined modality chemoradiotherapy as consolidation after maximal TURBT is an established option for patients unable to undergo surgery or seeking bladder preservation. Several trials have demonstrated encouraging outcomes with this approach and were highlighted in a large meta-analysis.37 Various chemosensitizing chemotherapeutic regimens have been evaluated, including cisplatin alone or as a doublet, gemcitabine alone, and 5-fluouracil plus mitomycin C, but no randomized studies have compared these regimens to each other, nor have they been compared to surgical approaches. However, this strategy remains an option as an alternative to surgery.