In this editorial, Anna Sureda, MD, PhD, details the need for new frontline treatments for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, including those with advanced stage disease.

Dr Sureda is head of the Hematology Department and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Programme at the Institut Català d'Oncologia, Hospital Duran i Reynals, in Barcelona, Spain. She has received consultancy fees from Takeda/Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Hodgkin lymphoma has traditionally been known as a cancer with generally favorable outcomes. Yet, as with any cancer treatment, there is always room for improvement. For Hodgkin lymphoma specifically, there remains a significant unmet need in the frontline setting for patients with advanced disease (Stage III or Stage IV).

Hodgkin lymphoma most commonly affects young adults as well as adults over the age of 55.1 Both age at diagnosis and stage of the disease are significant factors that must be considered when determining treatment plans, as they can affect a patient’s success in achieving long-term remission.

Though early stage patients have demonstrated 5-year survival rates of approximately 90%, this number drops to 70% in patients with advanced stage disease,2-4 underlining the challenges of treating later stage Hodgkin lymphoma.

Additionally, only 50% of patients with relapsed or refractory disease will experience long-term remission with high-dose chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)5-6— a historically and frequently used treatment regimen.

These facts support the importance of successful frontline treatment and highlight a gap with current treatment regimens.7-10

With current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatments, it can be a challenge for physicians to balance efficacy with safety. While allowing the patient to achieve long-term remission remains the goal, physicians are also considering the impact of treatment-related side effects including endocrine dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, lung toxicity, infertility, and an increased risk of secondary cancers when determining the best possible treatment.8-15

Advanced stage vs early stage Hodgkin lymphoma

Stage of disease at diagnosis has a large influence on outcomes, with advanced stage patients having poorer outcomes than earlier stage patients.7,15-16 Advanced Hodgkin lymphoma patients are more likely to progress or relapse,7,15-16 with nearly one third remaining uncured following standard frontline therapy.7-10

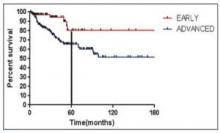

As seen in Figure 1 below, there is a clear difference in progression-free survival for early versus advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma.16

The difference between early stage and advanced stage patients treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) demonstrates the heightened importance of successful frontline treatment for those with advanced stage disease.16

Unmet needs with current frontline Hodgkin lymphoma treatment

Though current treatments for frontline Hodgkin lymphoma, including ABVD and bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP), have improved outcomes for patients, these standard regimens are more than 20 years old.

ABVD is generally regarded as the treatment of choice based on its efficacy, relative ease of administration, and side effect profile.17

Escalated BEACOPP, on the other hand, was developed to improve outcomes for advanced stage patients but is associated with increased toxicity.8-10,13,18

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans have also been identified as a pathway to help guide further treatment, but patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma may relapse more often, despite a negative interim PET scan, compared to stage II patients.19

Among current treatments, side effects including lung and cardiotoxicity as well as an increased risk of secondary cancers are a concern for both physicians and their patients.8-10,13-15

Similarly, radiation therapy, often used in conjunction with chemotherapy for patients who have a large tumor burden in one part of the body, usually the chest,20 is also associated with an increased risk of secondary cancers and cardiotoxicity.8-10,21

With these complications in mind, stabilizing the effects between improved efficacy and minimizing the toxicities associated with current frontline treatments needs to be a focus as new therapies are developed.

For young patients specifically, minimizing toxicities is crucial, as many will have a lifetime ahead of them after Hodgkin lymphoma and will want to avoid the risks associated with current treatments including lung disease, heart disease and infertility.8-10,12-15,22

Treating elderly patients can also be challenging due to their reduced ability to tolerate aggressive frontline treatment and multi-agent chemotherapy, which causes inferior survival outcomes when compared to younger patients.23-25 These secondary effects can affect a patient’s quality of life8-9,12,14-15,22,26-28 and exacerbate preexisting conditions commonly experienced by those undergoing treatment, including long-term fatigue, chronic medical and psychosocial complications, and general deterioration in physical well-being.22

Studies have shown that most relapses after ASCT typically occur within 2 years.29 After a relapse, the patient may endure a substantial physical and psychological burden due to the need for additional treatment, impacting quality of life for both the patient and their caregiver.22,26,30

Goals of clinical research

Despite its recognition as a highly treatable cancer, newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma remains incurable in up to 30% of patients with advanced disease.7-10 Though current therapies seek to achieve remission and extend the lives of patients, it is often at the cost of treatment-related toxicities and side effects that can significantly reduce quality of life.

Moving forward, it is critical that these gaps in treatment are addressed in new frontline treatments that aim to benefit patients, including those with advanced stage disease, while reducing short-term and long-term toxicities.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the W2O Group for their writing support, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

______________________________________________________

1American Cancer Society. What Are the Key Statistics About Hodgkin Disease? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

2Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner M-J (editors). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, NIH Pub. No. 07-6215, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

3American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Hodgkin Disease by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. Accessed February 16, 2017.

4Fermé C, et al. New Engl J Med, 2007.357:1916–27.

5Sureda A, et al. Ann Oncol, 2005;16: 625–633.

6Majhail NS, et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2006;12:1065–1072.

7Gordon LI, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:684-691.

8Carde P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2016;34(17):2028-2036.

9Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2009;27(27):4548-4554

10Viviani S, et al. New Engl J Med, 2011;365(3):203-212.

11Sklar C, et al. J Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2000;85(9):3227-3232

12Behringer K, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:231-239.

13Borchmann P, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2011;29(32):4234-4242.

14Duggan DB, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(4):607-614.

15Johnson P, McKenzie H. Blood, 2015;125(11):1717-1723.

16Maddi RN, et al. Indian J Medical and Paediatric Oncology, 2015;36(4):255-260

17Ansell SM. American Journal of Hematology, 2014;89: 771–779.

18Merli F, et al. J Clin Oncol, 34:1175-1181.

19Johnson P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419‑2429

20American Cancer Society. Treating Hodgkin Disease: Radiation Therapy for Hodgkin Disease. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkin-lymphoma/treating/radiation.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

21Adams MJ, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2004; 22: 3139–48.

22Khimani N, et al. Ann Oncol, 2013;24(1):226-230.

23Engert A, et al. J Clin Oncol, 2005;23(22):5052-60.

24Evens AM, et al. Br J Haematol, 2013;161: 76–86.

25Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Br J Haematol, 2005;129:597-606.

26Ganz PA et al. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21(18):3512-3519.

27Daniels LA, et al. Br J Cancer 2014;110:868-874.

28Loge JH, et al. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:71-77.

29Brusamolino E, Carella AM. Haematologica, 2007;92:6-10

30Consolidation Therapy After ASCT in Hodgkin Lymphoma: Why and Who to Treat? Personalized Medicine in Oncology, 2016. http://www.personalizedmedonc.com/article/consolidation-therapy-after-asct-in-hodgkin-lymphoma-why-and-who-to-treat/. Accessed February 16, 2017.