Researchers have found evidence to suggest that thrombocytosis is a strong predictor of cancer, particularly lung and colorectal cancer.

The team therefore believes patients with thrombocytosis should be evaluated for an underlying malignancy, as such investigation could speed up cancer diagnosis and save lives.

“We know that early diagnosis is absolutely key in whether people survive cancer,” said Sarah Bailey, PhD, of the University of Exeter Medical School in the UK.

“Our research suggests that substantial numbers of people could have their cancer diagnosed up to 3 months earlier if thrombocytosis prompted investigation for cancer. This time could make a vital difference in achieving earlier diagnosis.”

Dr Bailey and her colleagues described their research in the British Journal of General Practice.

The team conducted a prospective cohort study using Clinical Practice Research Datalink data spanning the period from 2000 to 2013.

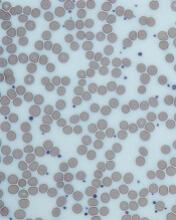

They compared the 1-year cancer incidence in 40,000 patients (age 40 and older) with thrombocytosis (platelet count >400 × 109/L) and 10,000 matched controls with normal platelet counts.

Patients with thrombocytosis had a higher incidence of cancer than individuals with normal platelet counts.

The cancer incidence was 6.2% (1355/21,826) in women with thrombocytosis and 2.2% (119/5370) in women with normal platelet counts.

The cancer incidence was 11.6% (1098/9435) in men with thrombocytosis and 4.1% (106/2599) in men with normal platelet counts.

If patients in the thrombocytosis group had a second raised platelet count recorded within 6 months of their index date, the risk of cancer increased to 18.1% for men and 10.1% for women.

Lung and colorectal cancer were more common among patients with thrombocytosis than among individuals with normal platelet counts.

And about one-third of patients with thrombocytosis and lung/colorectal cancer had no other symptoms that would indicate they had cancer.

In addition, the researchers found that “substantial proportions” of lung/colorectal cancer diagnoses could be expedited if thrombocytosis were routinely investigated.

The team calculated that if 5% of patients with cancer have thrombocytosis before a cancer diagnosis, one-third of them have the potential to have their diagnosis expedited by at least 3 months if their doctor investigates the possibility of cancer based on the presence of thrombocytosis. This equates to 5500 earlier diagnoses annually.

“The UK lags well behind other developed countries on early cancer diagnosis,” said study author Willie Hamilton, MD, of the University of Exeter Medical School.

“In 2014, 163,000 people died of cancer in this country. Our findings on thrombocytosis show a strong association with cancer, particularly in men—far stronger than that of a breast lump for breast cancer in women. It is now crucial that we roll out cancer investigation of thrombocytosis. It could save hundreds of lives each year.”