Credit: Lucien Monfils

Researchers say they’ve developed a technique that can predict—with 95% accuracy—which stroke patients will benefit from tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and which will suffer from intracranial hemorrhage if treated.

The team devised a method that uses standard MRI scans to measure damage to the blood-brain barrier.

If further tests confirm the method’s accuracy, the researchers say it could allow for more precise use of intravenous tPA.

“If we are able to replicate our findings in more patients, it will indicate we are able to identify which people are likely to have bad outcomes, improving the drug’s safety and also potentially allowing us to give the drug to patients who currently go untreated,” said study author Richard Leigh, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Leigh and his colleagues described their technique in Stroke.

The group’s method is a computer program that lets physicians see how much gadolinium, the contrast material injected into a patient’s vein during an MRI scan, has leaked into the brain tissue from surrounding blood vessels.

By quantifying this damage in 75 stroke patients, the researchers identified a threshold for determining how much leakage was dangerous.

Then, they applied this threshold to those 75 records to determine how well it would predict who had suffered a brain hemorrhage and who had not. The test correctly predicted the outcome with 95% accuracy.

The researchers noted that, until now, physicians haven’t been able to predict with any precision which patients are likely to suffer a drug-related bleed and which are not. In these situations, if physicians knew the extent of the damage to the blood-brain barrier, they would be able to more safely administer treatment.

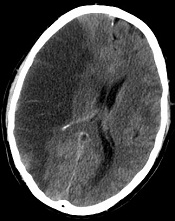

Typically, physicians do a CT scan of a stroke victim to see if he or she has visible bleeding before administering tPA. Dr Leigh said his computer program, which works with an MRI scan instead, can detect subtle changes to the blood-brain barrier that are otherwise impossible to see.

If his findings hold up, Dr Leigh said, “We should probably be doing MRI scans in every stroke patient before we give tPA.”

He conceded that an MRI scan does take longer to conduct in most institutions than a CT scan. But if the benefits of getting tPA into the right patients outweigh the harms of waiting a little longer to get MRI results, physicians should consider changing their practice, according to Dr Leigh.

“If we could eliminate all intracranial hemorrhages, it would be worth it,” he said.

Dr Leigh is now analyzing data from patients who received other treatments for stroke outside the typical time window, in some cases many hours after the FDA-approved cutoff for tPA. It’s possible, he said, that some patients who come to the hospital many hours after a stroke can still benefit from tPA, the only FDA-approved treatment for ischemic stroke.